UNITED KINGDOM:

Quentin Blake and John Yeoman: 50 Years of Children’s Books

A celebration of over 40 books created by Quentin Blake with writer John Yeoman. More details...

Where: Derby Museum & Art Gallery, Derby

When: Now until 3 October 2021

Ralph Steadman: Hidden Treasures

The first ever public display of three never-before-seen artworks by British satirist, artist, cartoonist, illustrator and writer Ralph Steadman. More details...

Where: The Cartoon Museum, London

When: Now until 10 October 2021

Black Panther & The Power of Stories

Three iconic costumes from Marvel Black Panther film - T’Challa, Shuri and Okoye - sit alongside Marvel comics, historic museum objects and local stories. More details...

Where: Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich

When: Now until 24 October 2021

V For Vendetta: Behind The Mask

This major new exhibition invites you to step inside the story and characters of one of the world’s most iconic graphic novels: V for Vendetta. Featuring original artwork by David Lloyd. More details...

Where: The Cartoon Museum, London

When: Now until 31 October 2021

Drawing Life

A new display showcasing the very best of the Cartoon Museum collection of cartoon art, curated by Guardian cartoonist and Cartoon Museum Trustee, Steve Bell. More details...

Where: The Cartoon Museum, London

When: Now until 31 December 2021

The Political Comics & Cartoons of Martin Rowson

Featuring Rowson’s most powerful political cartoons, caricatures and comics from the past forty years. More details...

Where: Kendel, Cumbria

When: 15 October to 5 November 2021

Beano: The Art of Breaking The Rules

Come face-to-face with the Beano gang through original comic artwork and amazing artefacts, plundered from the Beano’s archive. More details...

Where: Somerset House, London

When: 21 October 2021 to 6 March 2022

NORTH AMERICA:

George Bess: Tale of Unrealism

Featuring the stunning artwork of French artist, George Bess, best known for his collaborations with Alejandro Jodorowsky. More details...

Where: Phillippe Labaune Gallery, New York

When: 9 September to 5 October 2021

Drawn to Combat: Bill Mauldin & The Art of War

A retrospective of the provocative work by two-time Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin about a nation’s time of war, civil rights, and social justice. More details...

Where: Pritzker Military Museum, Chicago

When: Now until Spring 2022

Chicago: Where Comics Came to Life - 1880 To 1960

Curated by Chris Ware, and Chicago Cultural Historian, Tim Samuelson, this exhibition is a historical companion to the concurrently appearing survey of contemporary Chicago comics at the MCA. More details...

Where: Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago

When: Now until 3 October 2021

Chicago Comics: 1960s To Now

Telling the story of the art form in the influential city through the work of Chicago’s many cartoonists: known, under-recognized and up-and-coming. Featuring Chris Ware, Lynda Barry, Chester Gould and more! More details...

Where: Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

When: Now until 3 October 2021

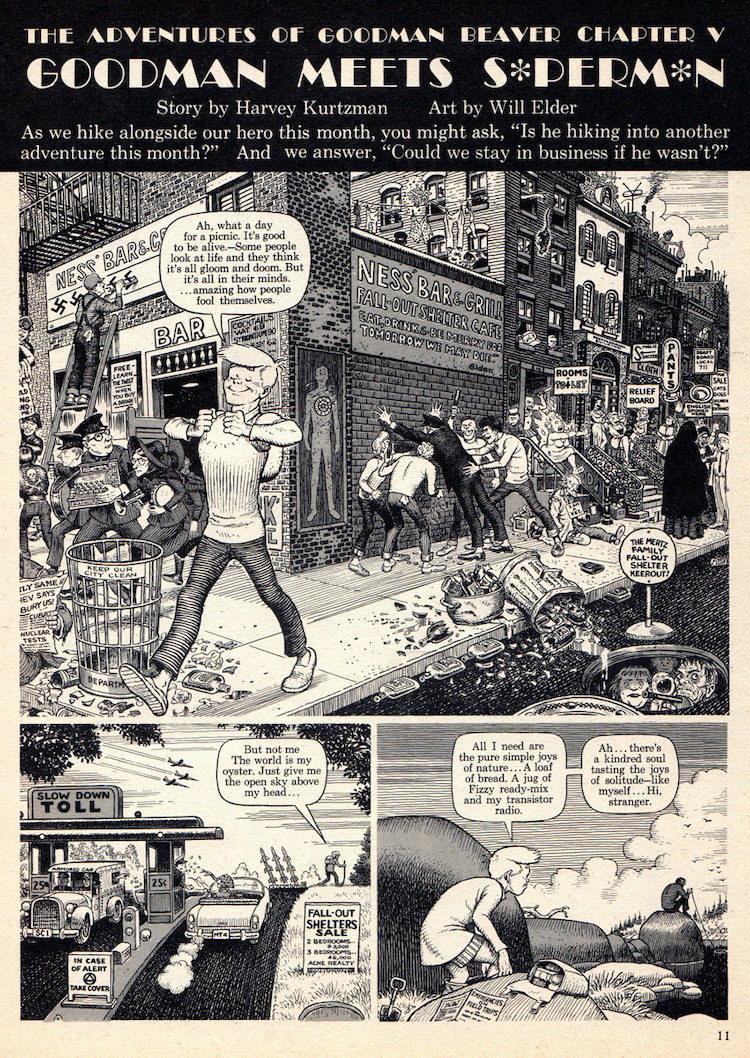

Society of Illustraors: Comic Art Exhibition & Sale

Over 180 pieces of original comic book art from EC, Marvel & DC, from 1935 up to the modern era. More details...

Where: Society of Illustrators, New York

When: Now until 23 October, 2021

Marvel Universe of Superheroes

Celebrating Marvel history with more than 300 artefacts - original comic book pages, sculptures, interactive displays and costumes and props from the Marvel blockbuster films. More details...

Where: Museum of Science & Industry, Chicago

When: Now until 24 October 2021

Walt Kelly: Into The Swamp

Celebrating Walt Kelly and his social commentary through the joyous, poignant, and occasionally profound insights and beauty of the alternative universe that is Pogo. More details...

Where: Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, Columbus, Ohio

When: Now until 31 October 2021

The Legend of Wonder Woman

An exhibition celebrating 80 years of DC Comics’ iconic Amazon. More details...

Where: Cartoon Art Museum, San Francisco

When: Now until 31 December 2021

Romanticism To Ruin: Reconstructing the Garrick

Focused on the lost buildings of Louis Sullivan. Co-curated by John Vinci, Tim Samuelson, Chris Ware and Eric Nordstrom. More details...

Where: WrightWood659, Chicago

When: 24 September to 27 November 2021

Hapless Children Drawings From Mr Gorey's Neighbourhood

Featuring a menagerie of youngsters who come to bad ends, and for that reason it’s suggested that you avoid establishing any emotional attachment to them. More details...

Where: The Edward Gorey House, Cape Cod, MA

When: Now until 31 December 2021

Marvelocity: The Art of Alex Ross

Featuring original art from his most recent book, Marvelocity, visitors will also learn about how Alex Ross developed into a great illustrator through his childhood drawings, preliminary sketches and paintings. More details...

Where: Canton, Ohio

When: 23 November 2021 to 6 March 2022

COMIC ART MUSEUMS & GALLERIES

UNITED KINGDOM:

British Cartoon Archive

By appointment access to over 200,000 cartoons and comics. More details...

Where: University of Kent, Canterbury

Heath Robinson Museum

A permanent exhibition dedicated to Heath Robinson’s eccentric artistic career. More details...

Where: Pinner, London

Orbital Art Gallery

The gallery space of an awesome comics shop. More details...

Where: Central London

Quentin Blake Center for Illustration

Soon to be home to Quentin Blake's archive of 40,000 works. More details...

Where: Clerkenwell, London

The Cartoon Museum

Celebrating Britain’s cartoon and comic art heritage. More details...

Where: Central London

V&A National Art Library Comic Art Collection

By appointment access to the Krazy Kat Arkive & Rakoff Collection. More details...

Where: South Kensington, London

EUROPE:

Basel Cartoon Museum

Devoted to the art of narrative drawing. More details...

Where: Basel, Switzerland

Belgian Comics Art Museum

Honouring the creators and heroes of the 9th Art for over 30 years. More details...

Where: Brussels

Hergé Museum

Explore the life and work of the creator of Tintin. More details...

Where: Belgium

Le Musee de la Bande Dessinee

A celebration of European comics culture. More details...

Where, Angouleme, France

NORTH AMERICA:

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

The world’s largest collection of materials related to cartoons and comics. More details...

Where: Columbus, Ohio

Cartoon Art Museum

Exploring comic strips, comic books, political cartoons and underground comix. More details...

Where: San Francisco, California

Charles M. Schulz Museum

Dedicated to the life and works of the Peanuts creator. More details...

Where: Santa Rosa, California

Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery

Bookstore and gallery space of the publisher of the world's greatest cartoonists. More details...

Where: Seattle, Washington

Frazetta Art Museum

The largest collection of Frazetta art. More details...

Where: East Stroudburg, PA

Norman Rockwell Museum

Illuminating the power of American illustration art to reflect and shape society. More details...

Where: Stockbridge, MA

Philippe Labaune Gallery

Comic art and illustration by emerging and established artists from around the world. More details...

Where: New York, NY

The Edward Gorey House

A museum dedicated to Gorey’s life and work and his devotion to animal welfare. More details...

Where: Cape Cod, MA

The Society of Illustrators

Dedicated to the art of illustration in America. More details...

Where: New York, NY