I first came across the work of Mr Reynolds back in the late 1980s when I was an artist working at Vortex Comics. One day, while avoiding work, I was flipping through the slush pile (unsolicited submissions) when I came across a graphically appealing two-page submission titled "The Lighted Cities". I can’t recall if Vortex used this strip or not, but the work stuck in my mind. Those two pages managed to create an evocative world that seemed fully formed yet offered very few details. Something was going on - but what? It was obviously the work of a talented artist and it also clearly hinted that it was a small piece of a larger whole. Later I came across his work again in Escape magazine... or possibly it was in a lone copy of Mauretania Comics that somehow found its way across the ocean. I can’t remember which. Either way, this second encounter set me on the job of trying to track down all of his work. This was not an easy task. Finding back issues of Mauretania Comics here in North America is next to impossible. Even finding them in Britain seems like a difficult process. In fact, I doubt I could have ever completed the collection without the help of the author himself. Still, it was a task well worth the effort.

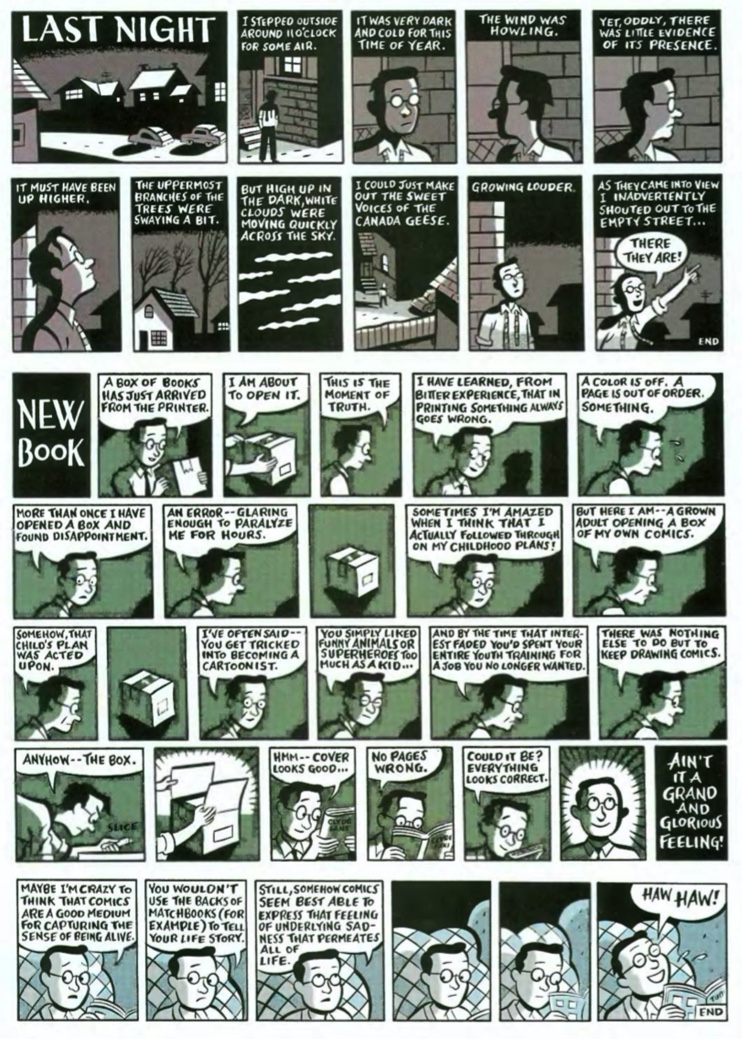

You might be wondering, “If it is so difficult to find these comics, then why are you bothering to tell me about them?” The good news is that Kingly Books of England has just released a collection of selected works from Mr. Reynolds titled The Dial and Other Stories. It has been 14 years since Penguin books published his brilliant graphic novel Mauretania (not to be confused with his series Mauretania Comics) and this new publication corrects a grave oversight that has kept his work out of the limelight for so long. It’s a cause for celebration. It also gives me an excuse to do something I have wanted to do for quite some time - write an appreciation of him and try to help bring his fascinating comics some of the attention they have sorely lacked. Chris Reynolds is a name you should know.

From the above paragraphs, I hardly need to mention that Chris Reynolds is an English cartoonist. He was part of that brief burst of cartooning energy that emerged in England in the mid to late ‘80s - mostly centered around Escape magazine — that included artists such as Glenn Dakin, Ed Pinsent, John Bagnall, Eddie Campbell and Phil Elliott. He self-published 16 issues of Mauretania Comics beginning in 1986 and in 1991 Penguin books published his graphic novel Mauretania. After that his appearances have been few and far between. This is a genuine shame. Being a cartoonist myself, I can only assume that he grew dissatisfied with the lack of obvious reward for such hard labor. Either that, or he just lost the passion for cartooning. Whatever the cause, I often regret that I don’t have ten more years of his work to add to the pile.

The very first issue of Mauretania Comics contains the subtitle "Mysterious stories about times and places" and no description could be more apt for the kind of stories that Mr. Reynolds tells. Times and places are certainly among his most important themes - but it is the word “mysterious” that best describes his comics. They are subtle, layered, and often oddly moving, but they are also deeply perplexing. This is not to imply that they are in some way overly obtuse in the way of so much modern gallery work. It is often the strategy of artists to present their ideas in a manner that is deliberately impenetrable to the audience in an attempt to cut off any criticism about the depth of its meaning. You can’t criticize something if you can’t grasp it. Reynolds is not afraid to put his ideas in the forefront of the story. He simply understands that a good mystery loses all of its power once it is solved. He masterfully manages to retain large enough gaps in its details to keep us wondering just what the big picture is. He is smart enough to have never filled in those gaps.

That said, Reynolds’ focus, as an artist is still clearly that of a world-builder. Even with all the gaps he’s purposely left he still manages to etch a striking portrait of a unique world. It is a place very much like our own - and yet not quite. It’s a parallel world, a slightly askew version of post-war Britain, perhaps. Certainly, it is very English in character The trappings of this parallel world turn out to be unexpected as the series goes along. For one thing there seems to have been some sort of war in outer space. And there are “aliens” walking around - particularly in the mining industry. There are strange organizations with names like the A.U.S., or "Rational Control'. One main character is possibly from another world - he definitely appears to have owned a spaceship at some point. Robots pop up occasionally and characters have returned from the dead once or twice. The setting could be 1950, or 1980, or possibly 2080. It’s a bit confusing.

This certainly doesn’t sound promising, does it? It’s almost a slight against Mr. Reynolds to bring up these details because they are so misleading. Reynolds smartly leaves these elements vague and unexplained. He hints at them but leaves us guessing. I’m sure he knows exactly the nature of his world’s history but I’m also sure he knows that to drag these things out into the light of day would expose them as trite, clichéd, and dull as ditchwater. By holding them back he recasts them into odd, surreal touches. The stories are never about these things anyway. They’re never about “things” at all. The stories are about feelings - especially those associated with specific places and specific moments. Mr. Reynolds’ characters are extremely sensitive to their own inner worlds. The science fiction elements are red herrings, simply there to muddy the waters.

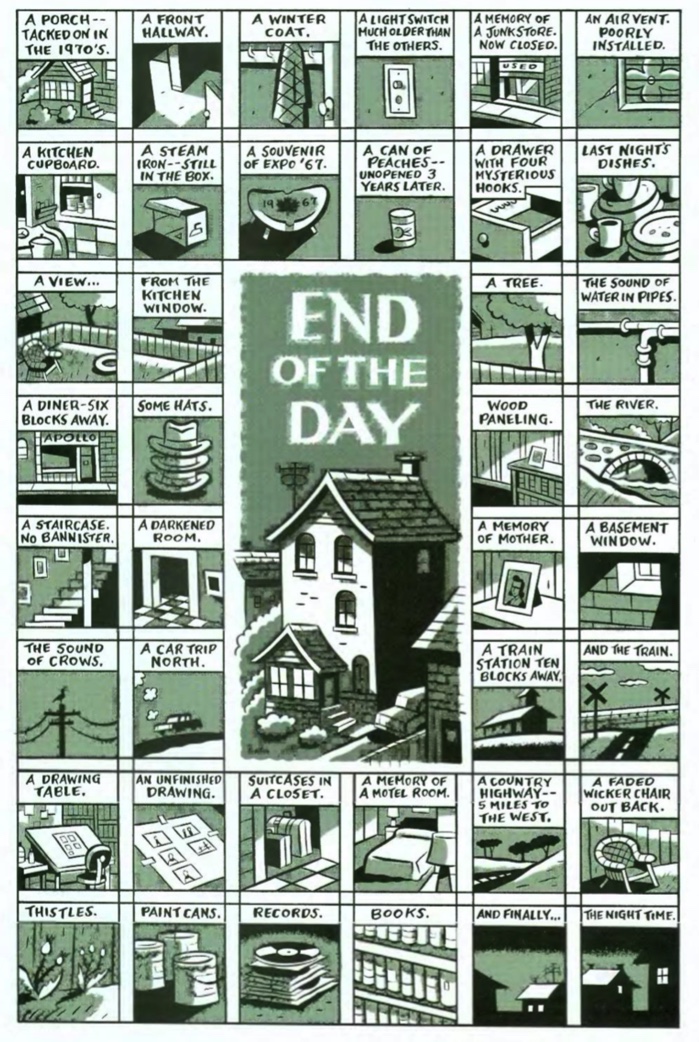

Few comics place such an emphasis on the setting as Mauretania Comics. Often the stories are actually about the setting and if it isn’t the main focus, you can be sure that it is a crucial element. His very style of storytelling is dependent on the impression given by lingering shots of buildings or landscapes. Occasionally whole pages will be given over to architectural scenes or clouds moving across the sky. The attention paid to these shots of building facades is just as important to the storytelling as the panels devoted to the characters. In many instances they supply the subtler details not given by the dialogue or narration. Sometimes they offer a counterpoint to what is being said.

The characters themselves are creatures of intuition. They follow their impulses more than their logical minds - even his detectives (mockingly labeled "Cinema Detectives") fit this template. In his graphic novel, Mauretania, he makes a clear statement favoring intuition over “Rational control.” Much of the characters’ intuition is linked to the feelings that places evoke. Mr. Reynolds seems very much in touch with the environment - especially the man-made environment. Like Edward Hopper, his places have a “charged” quality. Also like Hopper, he manages to convey the actual feeling of "being there". There is a rare sensitivity in the understanding of place that makes his comics a rich reading experience. They have a marvelous authenticity of place for a world that is so broadly etched.

Similarly interesting is his use of time. Time has a strange fluidity in his stories - past, present and future are not entirely separate. The stories do generally follow a linear path, but I detect an undercurrent in them: There is a cumulative effect that hints at a cyclical nature to the narratives. No one seems to ever leave the past fully behind. It’s not as though they are trapped by their pasts — nor is it purely nostalgia — it has more to do with the perceived feeling that the “past” exists somewhere as solidly as the events that are happening in the “present.” Perhaps it is memory that is lingering more than time. In Reynolds’ “Cinema Detectives” strips, the character Rosa inexplicably returns from the dead for no more reason than that she is willed back from the past. “Back by popular demand,” the narrator states. Mr. Ranger from “The Golden Age” stories appears to exist in several different time periods at once, as does another character from that series, Robert. None of the characters' relationships seem based on events that are occurring in the present. Their connections are always from an earlier period. Often stories focus around characters that are offstage — friends from long ago or people that are being sought. The odd thing about their absence is that one never has the impression that they are merely somewhere else — they always feel as if they are entirely absent from the world, as if they have ceased to exist in whatever time the story is set in. This is obviously my own personal impression and may have nothing to do with the intentions of the author.

I don’t want to give the impression that Mr. Reynolds never takes a misstep. Occasionally a story will spell out a little too much about his world and subsequently flatten the mystery a bit. Sometimes, he will push an idea too far into the absurd and have it become uncomfortably humorous. There is a lot of humor in his work, but in the best stories it keeps on the right side of absurd. Too much absurdity leads to conflict with the otherworldliness of his stories. Too far out and we lose the connection with our own world and, consequentially, our identification with the characters.

When it comes to the visual elements of the strips Mr. Reynolds’ work is of a very high order. He works in an idiosyncratic style reminiscent of woodcut artists — especially Masereel. Unlike other artists, who are trying for this look, with Mr. Reynolds it is merely a side effect of his heavy use of black shapes, his thick line work and his wide panel borders. It may have something to do with his uniform panel arrangement too.

Compositionally, his panels are beautifully put together. His understanding of shapes and their relationships within the panel (and the page) are very accomplished. His inking style, on the other hand, is eccentric. Lines are inked in with a bold thick line that often obscures detail — mouths and noses become blobs, small visual elements blur together. In cold type this sounds rather unappetizing but on the comic page it works surprisingly well — adding a freedom and fluidity to what could be very rigid compositions. He is quite fond of silhouettes and characters appear as black shapes for pages at a time. In general, the tone of the artwork is dark — even in bright sunlight the preponderance of shadow makes for a moody page design. He is a good designer. Several of the covers from Mauretania Comics are small masterpieces. At times, his hatching tends to be a bit fussy for my tastes and I tend to favor his strips that have a cleaner look. The artwork reached maturity by issue #2 and while there are peaks and valleys over the remaining issues, the actual evolution of the style is negligible. He reached a high mark early and remained pretty consistent overall. The Mauretania graphic novel is artistically a real high point though. The quality of the artwork generally depends on the effort (or interest) he showed in a particular story.

His storytelling style was also strikingly consistent. He unsparingly used a nine-panel grid and his narrative style always favored narration over dialogue. Again, these choices seem like drawbacks. Today’s cartoonists usually favor a more varied approach to storytelling and narration currently seems to be frowned upon in the “show don’t tell” school. Chris Reynolds is the exception to the rule because neither of these rigid sounding choices hurt his work in any way. His stories read very effortlessly and the staccato rhythm of his unflinching grid is perfectly wedded to his content. The stories seem made for it — which, I suppose, they were. The consistent use of narration blocks also add a natural distance between the reader and the character which is just the right choice if what you are trying to do is keep the character distant from the reader.

In the next few pages I intend to briefly discuss four wonderful short stories from the Mauretania Comics series and his masterpiece, the Mauretania graphic novel.

MONITOR’S HUMAN REWARD

This story appears in the second issue of Mauretania Comics and it just may be my favorite of all Mr. Reynolds’ stories. One of the first things that struck me about this strip is the jump in quality that occurred between issues one and two. Looking back at the run of Mauretania, the first issue is interesting but formative — it feels like early work. The second issue is instantly recognizable as mature work, a big creative jump.

This story is also the first appearance of Reynolds’ central character, Monitor. This character needs some explaining. In appearance, Monitor is a rather odd figure especially since the settings he appears in are so clearly a mundane, everyday world not much different from our own. Monitor is a slight figure, boyish really, dressed in a sort of spaceman’s uniform. It’s almost a child’s conception of a spacesuit. He wears a large round helmet and visor (with an “M” written on the side) that conceals his features (save for his nose and mouth), and on his back he sports a little backpack (rocket pack? schoolbag?). His costume is completely at odds with the other characters in his world. Still, the other characters rarely take notice or mention his odd attire. I have wondered if Monitor isn't possibly a character Mr. Reynolds created as a child (in a different context, of course) and cleverly transported into his adult work. Monitor’s name is a mystery in itself. Just what is he monitoring? By all indications he seems most intent on monitoring his own inner life.

The story, like all of Mr. Reynolds’ plots, appears simple at first. Monitor is on his way to the café where he works. He had taken the job on a lark — almost bullying the kind old lady who runs the place into hiring him, but now he’s grown disinterested with the work. This morning he had received an unexpected letter and he sits, on the steps of the house opposite the café, to read it. The letter informs him that he has just inherited a house. The house, it turns out, is she very one whose steps he’s sitting on.

He vaguely recalls some childhood connection to the place. He should report to work, but his desire to explore his new acquisition wins out. The door is not locked and when he enters the house he is surprised to find it is not the mundane place he expected.

On the surface, nothing much happens in this short story, but, like all good comics, it is in the telling that it comes to life. Reynolds sustains a wonderful calm throughout and the sense of place is palpable. As we move through the story we share Monitor’s gentle mood shifts as he experiences each new inner state of being. From the dissatisfaction of his job, to the perplexity of the unexpected inheritance, to his sense of wonder at exploring his new home, to, finally, his detached transformation into a new life. All in eight pages.

In many ways, this story sets up the blueprint for most of the stories to come. His most evident themes all take a short turn on the stage: a fascination with the sense of place; the persistence and mystery of memory; a concern with the effects of design; the potency of intuition; and some form of transformation (usually spiritual). A little bit of study shows that the first four themes add up to induce the final one — transformation.

In this case, the transformation begins when Monitor considers exploring his new house. His sense of responsibility to the old lady doesn’t have a chance against the excitement of that unknown building — “a mysterious world,” in Monitor’s own words. From the outside the house is a typical mid-century row house and that’s just what Monitor anticipates he will find inside, but he’s genuinely astonished upon entering to find a short hallway that immediately opens up into a large open-air space. A stone garden path leads up to a strange, crystal-domed structure (not much larger than a cabin). He goes in and finds the place warm (“like a summer house”) and looking through the clear walls he sees it has a spectacular view of the surrounding landscape. He’s also surprised to discover that the area around the house is more industrial than expected. A floating, windowless train is observed making it’s way down the river.

It is in these moments that Monitor is transformed. It is a subtle transformation — a simple and sudden shift in perspective. In a burst of intuitive insight he recognizes that he need never go to the café again. He will have to apologize to the old lady but she will forgive him. He will live the rest of his life in this house on the hill. This information is presented in a deadpan, matter-of-fact manner, and the reader is never misled into thinking that these are merely Monitor’s plans for the future. This is clearly information that has been intuited to him (from somewhere) by his presence in the house. This is the nature of personal transformation in Mr. Reynolds’ world. It comes about, most often, from a combination of time and place — not from circumstance or action.

THE SMALL MINES

From Mauretania Comics #5, another Monitor story. Monitor, it turns out, is actually a rather good character to “drop” into stories. He’s something of a cipher — a passive everyman. In this case, he’s taken a job as a mine agent. Monitor isn’t any clearer on what a “mine agent” is than I am. Nevertheless, he makes the best of it, moving into a shack down by the new mines. (What has become of Monitor’s home is anyone’s guess. Like I said, things tend to be somewhat fluid in these stories.) Given little actual job instruction, Monitor decides to show some initiative and draw a map of all the mine locations. He tours the various mines and meets some of their owners. At one location, over a ridge, he discovers some mysterious aliens running a mine. He watches their methods with interest. Monitor’s boss is pleased with his work. Some friends visit. The mines suffer hardship and then close up. Monitor takes on a new job and then some years later he pays a sentimental trip back to the area.

Mr. Reynolds relates this mundane story with such a quiet beauty that it is pure poetry. That famous “sense of place” that I keep harping on about is so clear and visceral in this strip that you have the impression that you’ve actually visited the area. As we follow Monitor on his various rounds we are treated to a virtuoso display of drawing and design as Reynolds produces some of his most potent use of landscape. His combination of gentle narrative and slow pacing creates a sustained mood that can only be compared to actual experience. If you’ve ever spent any time away from home wandering an unfamiliar town or city you will surely recognize the fascinated, yet slightly sad, feeling this experience inevitably creates.

In the middle of the story, Reynolds gives us a short talk on the relativity of place and feeling. Specifically, how a place becomes meaningful when you live there but also how difficult it is to impart that meaning to outsiders. This section particularly spoke to me. I’m sure, at some time or other, you’ve tried to show a visitor the charms of where you live — the places that are just so interesting to you — only to feel the feigned interest, or downright indifference, of your guest. Or perhaps you’ve been on the other side of this scenario — being shown the local sights by some host and feeling little about them. This is Monitor’s circumstance, exactly, when two friends visit him. In Reynolds’ own words: “Monitor had been looking forward to this visit by his friends for a long time but for some reason he didn’t think they appreciated the area very much when he showed them things. But that was alright, he supposed, because they had their own lives.”

That’s the key line: “because they had their own lives.” In it, Mr. Reynolds acknowledges that these places resonate for Monitor because they are his places — his life. Back home, these friends have their own places. It’s typically sensitive of Reynolds to recognize this condition and to draw our attention to it in a story where he is trying so earnestly to make us care about Monitor’s adopted countryside.

There are many such sharp human asides in this little seven-page story, and they are told with lovely understatement. The final page, where Monitor returns years later, has such a vivid melancholy to it and the ending trails off so sublimely that I hesitate to kill it by describing it here.

THE GOLDEN AGE

By this point it seems silly to mention that each issue of Mauretania Comics is made up of a variety of short stories — that must be self-evident. However, what I’ve neglected to make clear is that many of these short stories are part of individual series that have their own series-titles. These separate series are all interconnected but star different characters. There are the Monitor stories, the “Cinema Detectives” (starring Rosa), and the “Golden Age” stories (starring Robert). All of the Golden Age stories are identically titled “The Golden Age.” This particular one is from Mauretania Comics #8. It is the only “Golden Age” story from the series not reprinted in the current Kingly book.

These “Golden Age” strips usually begin with the words “years ago.” Evidently, they take place in the past. Further proof of this is the fact that Robert (a young boy) is one of Monitor’s school chums from when Monitor was a boy. Of all Mr. Reynolds’ work, these stories are the most baffling. Rational explanation is rarely offered for the events that occur and the reader quickly ceases to look for simple answers. The thought processes are those of a dream.

I’m not all that sure what Reynolds is trying to communicate in some of these stories. There is a quality of surrealist “automatic writing” about them. They can be very absurd. The timeline of this series-within-a-series (and they do follow some sort of an arc) appears to be, at least partly, cyclical. They certainly make a very interesting narrative puzzle. The “Golden Age” story I’m discussing here is the least absurd and most linear of them all. This one is actually pretty straightforward — that’s probably why it’s my favorite of the bunch.

The story: Robert is on summer vacation. He visits a local miniature railway, now in decline. He takes a ride but it ends abruptly when the train comes to a halt at the edge of a canal. This new canal has been built right through the middle of the rail line. Robert can see the continuation of the rails across the shimmering canal. Rails he will never ride. Summer passes and at the end of the holidays Robert pays a return visit. The miniature railway has closed down for good. Robert decides to re-join the severed rails. He gathers the materials from nearby sheds and builds a bridge across the canal. Robert stokes the engine of the miniature train and prepares for his ride. Just then, Mr. Ranger, Robert’s schoolteacher, arrives and informs him that school has begun. He then drags Robert away. The end.

There are several very interesting things about this strip, the first being how clearly it is a precursor to the Mauretania graphic novel (but more about that later). Another is the use of the train — or more properly, the rails. Trains often appear in Mr. Reynolds’ stories and I think he uses them because they are convenient symbols for “connectedness.” Rails, like wires, can be conduits for delivering things. In this case, the rails have been severed and whatever “message” they carried can no longer be transmitted. Because of this severed artery the railway dies. Robert understands this on an intuitive level and tries to reconnect them. Much like Monitor and his house, you anticipate that when Robert rides the train over the canal the message will be transmitted and Robert will be transformed. But unlike Monitor, Robert doesn’t receive his transformation — Mr. Ranger prevents it. This is interesting too. In later stories we get to know Mr. Ranger and he’s a rather unlikable character — stodgy, suspicious, and always after Robert (and his headmistress). Eventually, he joins the new Police Force named “Rational Control,” one of Reynolds’ few instances of rationality squelching intuition.

WHISPER IN THE SHADOWS

This is one of the “Cinema Detectives” strips. It’s the one where Rosa dies. Earlier, if you recall, I mentioned that Rosa returns from the dead in a later story. Her death is actually sad and when she does return there is a genuine desire (as a reader) to have things return to normal and for her happy life to pick up where it left off. Reynolds resists this urge and her return actually makes things awkward. Her family and friends have moved on and she doesn’t have a clear place in their lives anymore. Her husband, Jeff, has remarried. It deliberately fails to fulfil the reader’s emotional wants.

But back to her death. Rosa has been wounded while investigating a case and is holed up in the Doolan Hotel. Her young son, Jimmy, is caring for her. While he is out buying bandages, a man slips into the room. We cut to the funeral and then again to Rosa’s husband quickly remarrying (Sandra). Jimmy had met Monitor at the funeral and starts to imitate him by wearing a similar helmet. The only difference is that instead of the “M” that is on Monitor’s helmet, Jimmy paints a “II.” “I’m going to be Monitor Two,” Jimmy says. A year passes and Jimmy has persuaded Jeff and Sandra to take him back to the area around the Doolan Hotel. They visit a large hill nearby that he and his mother had visited shortly before her death. Jimmy takes off, running wildly, down the hill in an attempt to get back into the past. He fails. That night, back at the Doolan hotel, he cries as he finally faces his mother’s death.

On the surface, this story seems to be about a boy coming to terms with the death of his mother. Without reading further “episodes” I’d have to agree with that assessment. But knowing of Rosa's return and Jimmy’s role in the Mauretania graphic novel casts the story in a different light. It’s another transformation story. “Jimmy” is transformed from a sad little boy into one of Reynolds’ intuitive beings. The moment of transformation occurs when Jimmy puts on the helmet and symbolically becomes Monitor’s son. In the graphic novel we see that Jimmy is the character most able to receive “messages” that are coming from somewhere else. Intuition doesn't just come from inside (in this universe) — it is a way to connect to some mysterious source of information.

Jimmy’s actions on the top of the hill give us a hint to how it works. While standing there, he hears his father say the word “nowadays” in a sentence. This word, instantly picked up on by Jimmy, acts as a trigger: He sees it as a key to open the doorway to the past. This is the moment when he races down the hill, repeating the word over and over (like a mantra) as he runs. Like in other stories, Jimmy is invoking the power of time and place. He’s returned to the spot of previous happiness and sparked by the key word “nowadays,” he has guessed this is the moment. It sounds odd when written down, but within the context of the stories these actions don’t seem out of place. When he reaches the bottom of the hill, he closes his eyes and thinks: “Now I’m back!” Upon opening his eyes, we see (from his perspective behind the visor) his mother standing there. In the next panel he is alone. Still, he yells up the hill — “You’ll have to go now, Sandra.” Jimmy expects his old life to resume. It doesn’t and back at the Doolan hotel Jimmy realizes that he’ll “never be able to go places and change things like he’d thought Monitor could do.” This is an interesting statement in itself. Jimmy sees Monitor as a catalyst for change in the world. I’m not sure if that is Monitor’s role — but it certainly foreshadows Jimmy’s.

In the very last panel Jimmy (in bed, presumably all cried-out) hears (or maybe not — he may be asleep) a whisper in the shadows — it’s Rosa’s voice. When I first read this story I assumed this whisper to be a dream, or a ghost, or even a sad little boy’s longings. Knowing the rest of the stories, it reads like the first hint of Rosa’s return to the world. I must assume that Jimmy’s frantic run has actually worked. He’s brought back the past.

MAURETANIA

Finally, we come to the graphic novel. This, in my opinion, is Mr. Reynolds’ masterpiece. This is also the one publication you might easily be able to track down. In fact, at the time of this writing there are 14 copies available at www.abebooks.com. It’s a rich work but I’m going to try and keep this brief. A lot could be said about the book, as it definitely rewards repeated readings, however I’m going to focus on the story and its main theme. It’s safe to say that this is a distillation of the work that has come before. Mr. Reynolds has refined the details of his theme and presented it here in its purest form. The book is (as you’d expect, by this point) entirely about the conflict between rationality and intuition. It was only while working on this article that I also came to understand that this story brings a conclusion to the earlier works and an end to the Mauretania world.

The book opens with a factory closing. Fern Inc. has shut down and Susan, one of its employees, has just turned down the offer of a lift into town by her ex-boss, Alf, so that she can explore a “mysterious” little stream that she has watched from her office window every day. Susan follows the little stream through the gathering dusk until she spies a helmeted man sitting alone in a car silently watching the closed factory. The fact that Susan has finally given in to her whim to explore the stream says a lot about her as a Reynolds character. She’s making a shift from everyday reality into the world of more mysterious information. That the stream leads her to Jimmy confirms this. In many ways, Susan is Reynolds’ most fully realized character. She’s written in broad strokes and we certainly don’t get a lot of information about her beyond the essentials — but she does have a feeling of authenticity to her. She feels like a real person and unusually (for a Reynolds story) we share her inner thoughts. We relate to her and her problems — her lost job, her failed romance, the unwanted sense of intimacy with Alf, her overly concerned mother. She is someone from our world.

Quickly after Fern Inc.’s closing, Susan unexpectedly gets a job offer from Reynal Industries (a name which is surely some kind of word play — though I can’t figure it out). Sure enough, Alf has been hired too. The work at Reynal is suspiciously vague and her new boss, Tony, is unnaturally interested in Fern and its closing. It's all he really wants to talk about. With minimal sleuthing on Susan’s part she discovers that Reynal is a front for “Rational Control — the trendy new police force.” Susan immediately goes to Tony and spills the beans. Here, the tone of the story changes.

Now that Reynal’s front is exposed, Rational Control comes clean. It turns out that they are watching Jimmy. They’ve hired the ex-employees of recently closed factories because Jimmy has somehow been involved in their failing and they’re poking around for information. Rational Control is at a loss to explain how Jimmy’s done it. They’ve even managed to get ahold of one of Jimmy’s helmets but “There was no receiving device — nothing.”

Susan is drafted into their plan to find out more. They send her across the street (Jimmy’s office is just across the way) to apply for a job. Jimmy and Susan meet. Jimmy has grown up now, he’s not a child any longer, but he still wears his helmet with the II on the side. He is still symbolically Monitor’s child. He appears to have fulfilled his wish to “go places and change things.” Jimmy and Susan have an odd yet open conversation. She asks what Jimmy’s company does. Jimmy replies: “Well, it’s unusual work. We close down factories that are ‘harmful’ and that sort of thing. We do a few more positive things but that’s what we’ve been doing lately. That’s why I closed Fern down. I mean, it wasn’t anything personal or anything, and I’m sorry I had to do it, in a way. You know, quite a good looking building even.” Then Jimmy points across the street and lets Susan know that he is aware that Rational Control is watching him. “They’re not ready to close me down yet, though,” he says.

Later, Rational Control, still utterly baffled, sends Susan back across for more information. In a beautiful five-page sequence Susan silently crosses the street (carefully showing us the details of the streetscape) and enters Jimmy’s office. Not finding him there, she explores the dark back office (in a terrible state of decay) until she finally emerges into what looks like a prison yard (high walls and barbed wire) where Jimmy is sitting at a patio table. For a mysterious figure, Jimmy is amusingly unthreatening. Like Monitor, he is a slight figure, and with his big round helmet he is rather absurd-looking. His greeting doesn’t exactly inspire awe either: “Hi Susan — its a nice day.” Over the next eight pages of conversation (interspersed with scenes of moving clouds) we learn what Jimmy is doing. In halting dialogue between the two we come to understand that Jimmy’s conception of why the factories are “harmful” is not as commonplace as something like environmental damage — it’s somehow vaguer yet more important. Although what it is we do not learn. We do, however, discover his methods for closing them.

Jimmy tells Susan that there are special “points” that affect things and “you have to do things at the right time.” For example, this morning all he had to do was buy some children a kite. Susan asks him how he knows when to do these things? Jimmy replies: “Well, I don’t really.” It’s a telling statement. Jimmy doesn’t know — he feels. It’s hard not to view Jimmy as a kind of Zen figure and his effect on Susan is certainly like a master provoking her into an enlightened experience. In fact, in the very next sequence when Susan leaves Jimmy and re-emerges into the street we are treated to a marvelously understated scene that undoubtedly shows that Susan has been transformed. She steps into the street, and mirroring her walk across the street 20 pages earlier, she stops to observe the streetscape. In four brilliant panel transitions (each showing Susan standing and looking) we shift from a dead-on shot, to a worm’s-eye view, then, Susan hesitatingly turning back towards Jimmy’s office and then back to the original dead-on shot. Simply, Susan has experienced a change in perspective. She sees the world in different terms. From this point in the story, she is on Jimmy’s side.

While Susan was with Jimmy she noticed something odd about his movements. When Jimmy walked somewhere he always retraced his steps exactly in coming back, touching again every object that he had touched before. Later, Rational Control raids Jimmy’s office, rounding up his employees (though not catching Jimmy). One of his employees comments on this queer aspect of Jimmy’s behavior: “It’s as if, recently, Jimmy had some sort of imaginary wire behind him. If he went somewhere he always had to come back exactly the same way.” This isn’t the first overt mention of wires. Just pages earlier, Rational Control had become quite excited upon discovering an overhead wire between their building and Jimmy’s office. A red herring. It was just a normal electrical wire — nothing important.

But wires are important. It’s the central image of the book. It’s right on the cover. Like the stream Susan follows to Jimmy, wires contain currents — perhaps “undercurrents” is a more precise term here. These undercurrents in the world are the sources of Jimmy’s mysterious information. He’s the receiver at the end of the wire. Back at Rational Control one of the officer’s suggests that perhaps Jimmy’s information is from a spiritual source. For a moment Rational Control considers it: “In that case, there’s nothing we can do! If it’s God telling him what to do, and it works, then there’s nothing anyone can do.” They quickly retreat from this position — preferring to see Jimmy as a con man. Suddenly, during all this discussion at Rational Control, the power goes out. Even the phones are dead. Confusion sets in and everyone disperses. Susan finds herself alone in the street. Sensing that the power failure was one of Jimmy’s “points” she feels that Jimmy must surely be behind it and so she makes her way to the power station. Inevitably, she finds him there. Jimmy and Susan notice that one of the telephones is different from the rest and, sure enough, it’s still working. They follow its long wire out the door and far into the countryside where for 10 silent pages they trace its source. In the end it turns out to be nothing more than an experimental portable phone being tested by a field truck. Rational Control shows up, having also deducted that the power station was important.

In what seems like an anticlimax, everyone ends up on the hill overlooking the power plant, just standing around. Then a call on the portable phone reveals that the power failure was caused by some kids playing with a kite. The meaning is lost on Rational Control but, of course, we understand. Just then, Susan thinks of something: “Are you going to follow the wire all the way back this time Jimmy?”

This is the real climax of the story. Jimmy intuits that it’s time to cut the wires — to sever the umbilical cord between himself and the mysterious information source. “I have to go across there — without going back the way I came along the wire — that'll be the last thing I have to do.” Jimmy tells Rational Control, “You just have to let me go. Really I think it will change the world.” So Jimmy runs back across the field in a series of brilliantly crude drawings (which perfectly convey the look of a shimmering light on a hot summer day) and the world changes. The wires vanish. Literally.

Just how the world changes we never know. Honestly, what concrete details could Mr. Reynolds supply that would satisfy the reader? One thing we do learn though is that Rational Control is out of business. We see them packing up their files and we overhear Tony say: “Now that the world is perfect they don’t need us anymore.” So clearly, Mr. Reynolds’ perfect world is not formed through rational thought. Another humorous detail is the proliferation of wireless phones. The book ends on a happy scene between Jimmy and Susan.

It's a marvelous book and it brings a resolution to the world of Mauretania that is unexpected, absurd, funny and satisfying. In that “Golden Age” story from a few pages back we see the echoes of this one. There, Robert tries to connect the rails (wires) toward some mysterious end, but he’s stopped by rationality. Here, Jimmy manages to change the world by severing them. Rationality fails to stop it this time. And if there is one point I’ve failed at — it’s in conveying what an enjoyable read these stories are. The graphic novel is a positive page-turner. In the end, it turns out that Mr. Reynolds (or his characters, at least) have a deep belief in feeling over thought as a positive force in the world. I’m not sure I share that viewpoint, but within the context of his universe it’s a convincing idea. However, I must say, the deck is stacked. The characters who represent rationality are a boring group of old sticks-in-the-mud — not very likeable. Your sympathies always lie with the intuitive types. While writing this article, I came to a new appreciation of just how well thought out and consistent Reynolds’ work is. What appears to be, upon first reading, a world of odd, disjointed events turns out to be an internally coherent worldview.

It was genuinely difficult to keep to these five stories. The series contained many worthy strips that I was tempted to talk about. “Soft Return” from the final issue was particularly hard to leave out — a beautiful strip. I’ve deliberately omitted “The Dial” because I want to let you experience it yourself in the Kingly book. It’s an important story in Mr. Reynolds’ universe — a highly complex work open to a wide range of interpretations. I can’t emphasize enough that you should go and buy that book. Hopefully, if it is successful, further books will appear collecting the rest of Chris Reynolds’ work. He’s a cartoonist of the first rank. Unique. Remember his name.

Seth is a cartoonist living in Ontario, Canada. His works include the graphic novels It’s a Good life if You Don’t Weaken, Clyde Fans and George Sprott which are available from Drawn & Quarterly.