Having lived in Chicago for thirty years, I’ve only ever been a visitor to New York, but I love it like no other city. Teeming with unpredictable people and unimaginable places and unforeseeable moments, life there is measured not in hours but in densely packed minutes that can fill up a day with a year’s worth of life. Lately, however, closed up in our homes against a worldwide terror, time everywhere has seemed to slur, to become almost Groundhog Day-ish, forced into a sort of present-perfect tense - or, as my fellow New Yorker contributor Masha Gessen more precisely put it, ‘loopy, dotted, and sometimes perpendicular to itself.’ But disaster can also have a recalibrating quality. It reminds us that the real things of life (breakfast, grass, spouse) can, in normal times, become clotted over by anxieties and nonsense. We’re at low tide, but, as my wife, a biology teacher, said to me this morning, ‘For a while, we get to just step back and look.’ And really, when you do, it is pretty marvellous.

As the resident stay-at-home cartoonist, stay-at-home dad and stay-at-home laundress of my family, I knew some paradigm had shifted when I could no longer tell my wife’s clothes from my daughter’s. Soon, shirts were being traded. Then shoes. Sounds of footsteps on the stairs became indistinguishable, and I found I had to wait to adjust my speaking tone to see whom I was scolding for not hanging up a sweater. Five years - only five years! - since I was helping my daughter into a bike seat to take her to second grade, and now I could barely kiss the top of her head, though she could now kiss my wife’s. It’s cliché and it’s sentimental but it’s true: parents, when your child asks, “Will you play with me?” - do. Because one day they really will stop asking, just like you did.

I lived in San Antonio in high school, in the mid-nineteen-eighties, and attended college in Austin, occasionally driving to Houston with my fellow art students to visit museums, and sometimes alone, just for the change of scenery. I liked Houston for its big buildings, its diversity, and its slack zoning laws, which made neighborhoods unpredictable and surprising. One night, my cartoonist friend John Keen and I stopped at a restaurant-bar that was about halfway to Houston, in the very Texas-sounding town of Winchester. The parking lot was locked and loaded with about two dozen pickup trucks, and, as scrawny liberal Austinites, we braced ourselves and pushed open the saloon doors, only to find black and white farmers talking and laughing, playing poker, and shooting pool together. In a corner, an interracial couple quietly ate barbecue. This Winchester bar, we realized, was more integrated than the University of Texas we’d just left.

Most mornings, after I drop my eleven-year-old daughter off at school in Oak Park, Illinois, I drive my wife to the west side of Chicago, where she works as a teacher in a public school. Along the way, we’ll frequently pass a few of her students waiting for the bus, huddled in hoodies with their backward backpacks and my wife 0 it’s against Chicago Public School policy for a teacher to offer rides to students - will recognize and wave at many of them, citing an affectionate anecdote (“He’s one of the smartest students I’ve ever had”) or a bracing detail (“She beat up her boyfriend”) or a horrifying story (“His brother got shot”).

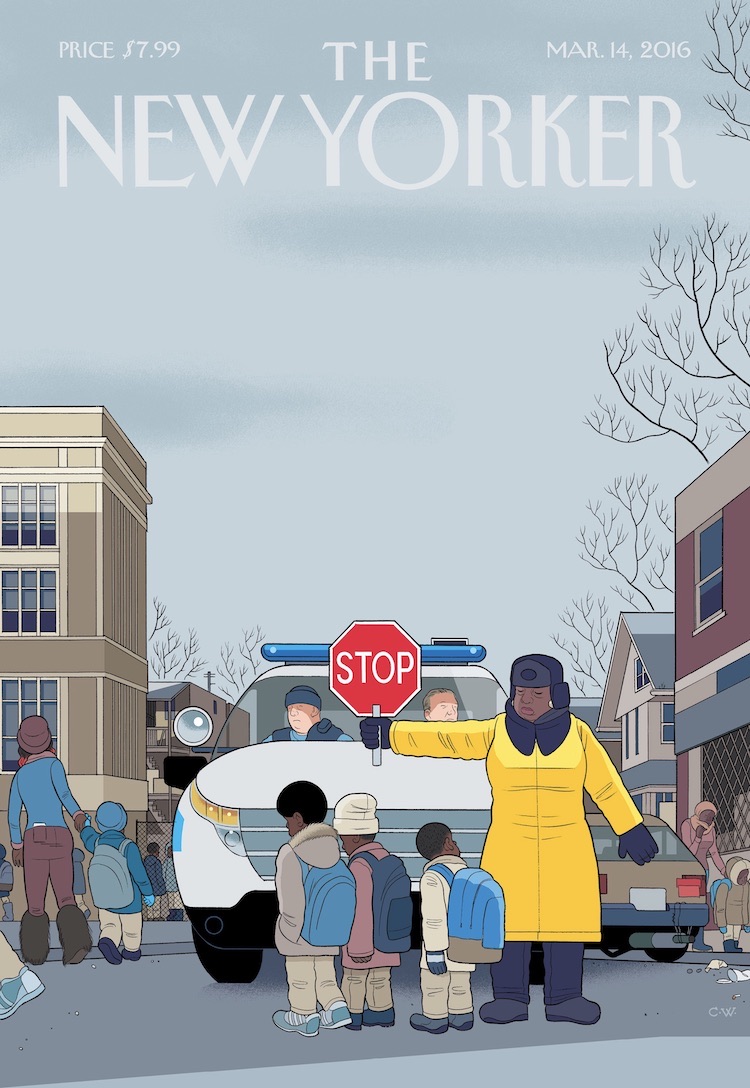

Stationed among these students are the crossing guards, all of whom are Chicago Police employees. In the outer peripheries work the Safe Passage guards, hired by the city when fifty schools were closed in 2013, lengthening the daily walks, drives, and bus rides of thousands of students to reassigned schools through neighborhoods identified as gang territory, just because they have streets and corners. Nearly all of the Safe Passage guards are middle-aged African-American women, and they nearly all recognize us and wave and smile, braving icy temperatures for hours every winter morning and afternoon. Our favorite is an energetic lady who spins around and sings to herself in the middle of the street, luring and halting traffic with graceful pirouettes that make it look as if she’s controlling the cars as part of some larger, secret ballet. However, she can turn on the cars just as easily: we’ve seen her scream at disobeying drivers, smacking her stop sign on the pavement with rage. Once, she even yelled at me, tearing through the fabric of our years-long silent code of friendship, when I guess I didn’t slow down fast enough.

Last week, as we gingerly crept through her intersection, my wife noted the sorry state of her sign, new at the beginning of the school year but now showing its battle damage: the top chipped, bent and curled down nearly halfway through the lettering, the consequence of it being slammed to the ground, over and over.

The New Yorker is arguably the primary venue for complex contemporary fiction around, so I often wonder why the cover shouldn’t, at least every once in a while, also give it the old college try? In the past, the editors have generously let me test the patience of the magazine’s readership with experiments in narrative elongation: multiple simultaneous covers, foldouts, and connected comic strips within the issue. This week’s cover, “Mirror,” a collaboration between The New Yorker and the radio program “This American Life,” tries something similar. Earlier in the year, I asked Ira Glass (for whose 2007-2009 Showtime television show my friend John Kuramoto, d.b.a. “Phoobis,” and I did two short cartoons) if he had any audio that might somehow be adapted, not only as a cover but also as an animation that could extend the space and especially the emotion of the usual New Yorker image. I knew that Ira was the right person to go to with this experiment in storytelling form, because he’s probably one of the few people alive making a living with a semiotics degree.

So he sent me an audio story, and, after coming up with a cover image based around it, I set to work with John Kuramoto to somehow animate it. Usually, when listening to a story, one’s mind not only sees but also feels in images; you imagine and constantly revise and update entire tableaux, much the way you imagine things while reading a book. I hoped that our pictures wouldn’t interfere with that ineffable mental dance but would somehow, like my usual medium of graphic novels, complement it. In fact, it seems to me that much of what we “see” in our everyday lives isn’t in front of us at all but within our memories and imaginations. I’ve noticed as my daughter Clara has grown older that the unfocussed “not seeing what’s in front of her because she’s lost in thought” look has become, perhaps sadly, more and more common. Then again, it’s what I do all day.

In the weird synchrony of life imitating art (or at least of life imitating half-finished New Yorker covers), this year ten-year old Clara’s Halloween costume employed as its crucial component the application of “scary/sexy” makeup. You know - black lipstick, green eye shadow. Though it was a sinister look, her strategy had an innocent purpose: she just wanted to try on lipstick. Worried, I did some intel with the local moms and discovered, not surprisingly, that this same costume idea seemed to be a coördinated plan within many of the pre-teen sleepover cells in our neighborhood. But I wasn’t ready for this moment, and neither was my wife; for years, my daughter had yelled at her mom for putting on lipstick because it made her “look fake.” But now, dear God, she wanted to see what it looked and felt like herself - the first application of a fiction to mask her remaining few months of childhood. This led to some convoluted car discussions. “Dad, if you say women are doing it just to accommodate men, then what are men doing to accommodate women? You’ve always said women can do anything men can, right? So, as a woman, I want to wear makeup!” And so on. But - point taken.

The question was complicated even further when, in a chat with a friend, I grumbled, like lots of people at the time, about Hillary Clinton’s seemingly tone-deaf statements about her use of a private e-mail server. “Why can’t she just apologize and play nice?” I pleaded. My female friend, taking a moment, offered, “Well, as a woman she’s being held to a different standard.” Point taken, again. The adage about working twice as hard for half as much. Or: maybe I’m just not as great a guy as I thought I was.

Of course, the most important people here are the subjects of the story: Hanna Rosin (the co-host of NPR’s “Invisibilia” and a writer for the Atlantic and Slate) and her daughter, and they are not at all fictional. But the interpretations that John and I have provided more or less are. Thus, my apologies and thanks to Hanna and her daughter both for any and all liberties taken. The video’s music, by Nico Muhly, was composed and performed especially for this cartoon, so most grateful regards to him as well and to the musicians who recorded it: Nathan Schram, on viola, and Fritz Myers, on piano.

No comments:

Post a Comment