The eponymous possum had first appeared as one of several anthropomorphic spear-carriers in the first issue of Animal Comics (December 1942 - January 1943). And when Kelly became art director of the short-lived by much mourned New York Star in 1948, he reincarnated his animal ensemble as a comic strip on October 8. After the Star's demise, Pogo went into national syndication, May 16, 1949.

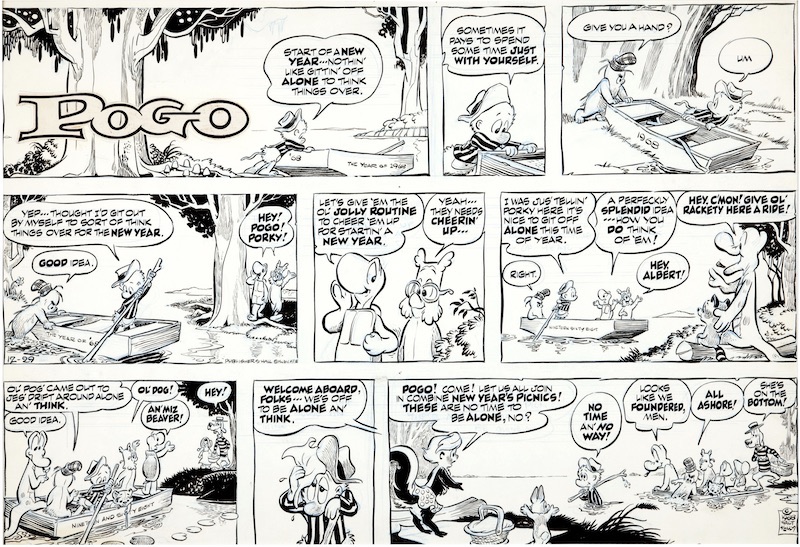

Pogo transcended the "talking funny animal" tradition of its origins. At its core, the strip was a reincarnation of vaudeville, and its routines were often laced with humour that derived from pure slapstick. To that, Kelly added the remarkably fanciful and inventive language of his characters - a "southern fried" dialect that lent itself readily to his characters propensity to take things literally and permitted an unblinking delight in puns. The cast was perfectly content being animals, but sometimes for their own amusement they'd undertake the enterprises of people, adopting the right jargon and costumes but not quite understanding the purpose behind the human endeavours they mimicked. Adrift in misunderstood figures of speech, mistaken identities, and double entendres going off in all directions at once, Kelly's characters usually wandered further and further from what appeared to have been their original intentions. And this was the trick of Kelly's satire: readers couldn't help but glimpse themselves in this menage, looking just as silly as they often were. The animals - "natures screechers" - were blissfully unaware of their satirical function. They, after all, didn't take life as seriously as people did: "It ain't nohow permanent", as Porky the porcupine was won't to say.

Kelly added overt political commentary to his social satire in 1952 when some of Pogo's well meaning friends entered him in the Presidential race, and the strip was never quite the same again. The double meaning of the puns took on political as well as social implications, and the vaudeville routines frequently looked suspiciously like animals imitating officials high in government. Over the years, Kelly underscored his satirical intent with caricature: his animals had plastic features that seemed to change before the reader's very eyes until they resembled those at whom the satire was directed. And the species suggested something about Kelly's opinions of his targets. Soviet boss Nikita Khrushchev showed up one time as a piratical pig; Cuba's Fidel Castro as a goat; the tenacious J. Edgar Hoover as a bulldog.

Kelly's first foray into the jungle of politics with caricature as his machete was in the spring of 1953, when he introduced an unprincipled and purely ruthless operative in his swamp, a wild cat named Simple J. Malarkey. As if the syllabic rhythm of his name weren't give away enough, Kelly made the wild cat look remarkably like Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, the country's self-proclaimed crusader against communist spies, a master of the smear and innuendo with a gift for the self-promotion and an utter disregard for the truth. To create a narrative metaphor for McCarthy's commie hunt, Kelly turned to the swamp's Bird Watcher's Club, and in power plays evocative of McCarthy's manoeuvres, Malarkey intimidates the members of the club into letting him take charge. With his guidance, the Club dedicates itself to ridding the swamp of all migratory birds, and when Malarkey is faced with a number of swamp creatures who claim they aren't birds (because, in fact, they aren't), he proposes to make them all birds with "a little judicious application" of tar and feathers. At one satiric stroke, Kelly equated McCarthyism with an appropriately belittling analogue, tar-and-feathering - a primitive method of ostracising, universally held in low repute. In a delicious finale, a member of the Club shoves Malarkey into the kettle of tar, demonstrating with an unforgettable flourish that those who seek to smear others are likely to be tarred with their own brush.

It was as neat a piece of satire as had ever been attempted on the comics page or anywhere. And the success of it depended upon Kelly's plumbing the potential of his medium to its utmost. Word and picture are perfectly, inseparably, wedded, the very emblem of excellence in the art of the comic strip: neither meant much when taken by itself, but when blended, the verbal and the visual achieved allegorical impact and powerful satiric thrust. High art indeed. At its best, Pogo was a masterpiece of comic strip art, an Aesopian tour de force - humour at each of two levels, one vaudeville, the other satirical - and it opened to a greater extent than ever the possibilities for political and social satire in the medium of the newspaper comic strip.

No comments:

Post a Comment