Three classic Briggs stories are reproduced complete and at full size, with the same values as their original appearances. These are Father Christmas (1973), The Tin-Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman (1984) (a satirical comment on the Falklands war that is nowadays difficult to find, if not out of print) and The Bear (1994). Two others are presented complete but in reduced size: The Elephant and the Bad Boy (1978), a fine early example from the period before Briggs customarily illustrated his own texts, and The Snowman (1978), the most famous of the Briggs books, of which the animated adaptation is a standard Christmas television event in several countries. All his other books are visually represented with several pages or excerpted panels, with special mention due to the handful of pencil roughs for Ethel & Ernest in the endpapers. There is not a great deal of this kind of thing for the technical enthusiast or art specialist, though I should not forget to mention some preparatory sketches for an abandoned sequel to Fungus The Bogeyman (1977). The attention to dates that you see here reflects the similar attention to bibliographical particularity in the book itself.

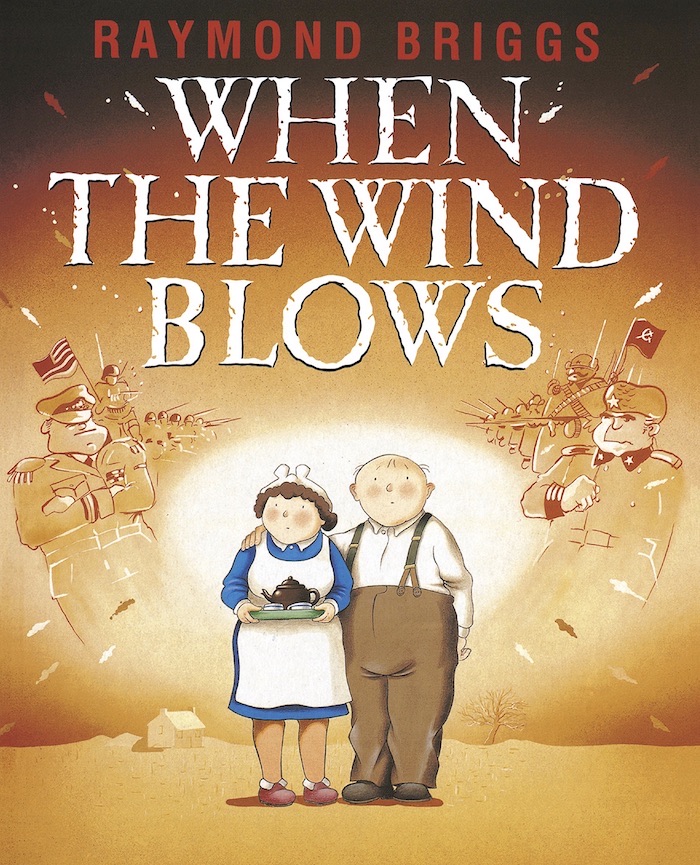

Seeing it all gathered together like this, I am most impressed with the consistency of theme with Briggs' world. The commentary, written by Nicolette Jones, makes the best use of this by organising the material not strictly chronologically but around a series of connections. This enables us to see clearly, for example, the marries couple, Jim and Hilda, in Gentleman Jim (1980), an almost tragic story of a toilet attendant with ideas above his station, are the same hapless Jim and Hilda of When The Wind Blows (1983), in which they are victims of the nuclear war that has appeared to be more or less imminent over the last 50 years.

My first encounter with Briggs was the Father Christmas book. I can't remember how I would have come across it, since it presented itself to the world as a children's book and I was 18, no longer a child and not yet back into the kid's book market on behalf of my own kids, when it was published. I can only suppose that my instincts for sniffing out the true comic strip, no matter what shape-shifting form it might assume, were by then fully functioning. Just as remarkable was the fact that Brian Bolland, three years ahead of me at the same college and by now a good friend, had also happened upon it independently. I found this to be true in later years also, that my kind of people all had their personal fondness for Briggs without ever having discussed it among ourselves or agreed that he was of our ilk (that we are artistic kin, so to speak). For example, horror maniac Steve Bissette staying with me in Brighton in 1985 while over for the London Comic book convention, had to make time for a detour to try and locate a copy of the Fungus The Bogeyman Plop-Up Book (1982).

Father Christmas was the one where Briggs first went over wholeheartedly to the comic-strip medium as his format of choice. "It was the pressure of space that forced me into the labour-intensive botheration of strip cartoons. In 1972, while working on Father Christmas, I found I needed far more than the 32 pictures of the standard nook (meaning children's picture book), and more even than the 64 of two pictures per page. There was so much to go in that 10 or more pictures per page were needed, so leading straight into the bottomless abyss of strip cartooning," wrote Briggs in a recent article in the Guardian newspaper. All the words are hand-lettered, with direct speech contained in freehand word balloons. Furthermore, he seemed to be aware of the innovations that had been taking place in comics around that time, and of the seriousness with which the form was being taken in some circles. He established a system of four tiers of panels, which he would combine and expand, enlarging into big double-page vistas when the action invited, and there are several places in the 32-page book where this happens.

Whatever came before Father Christmas was always vague to me, Briggs' prehistory. In fact, he was by then a highly respected and successful illustrator, having been in continuous publication since 1957. In Blooming Books, the "early years" are given more information on this part of his career than I have so far seen. Then there are 11 pages on "the nursery classics". The Mother Goose Treasury (1966) tends to be the earliest book still mentioned in the artist's resume. It's much more fun than you would expect. There's an image of a man riding a flaming wheelbarrow as one of the five sprightly vignettes around the verse of "The Mad Man." An enchanting page of watercolour and newspaper collage frames "If all the world were paper." There are over 800 separate drawings in this intoxicating rush of a book. Having brought up three children, I feel an odd encroaching sadness that I didn't have this wonderful book to hand through those years, along with all the other favourites of me and my wee ones. such as Bill Pete's Huge Harold and Scroggy (the monster who was afraid of the dark), the name of the author of which is no longer retrievable from the filing system of my head. But his career, in so far as it interested me (and my ilk), started with this grumbling little Santa Claws, whose "blooming Christmas" catchphrase gives the current volume its title. Two years later there was a sequel, Father Christmas Goes on Holiday (1975), rendered just as lovingly in the same style. In 1979 I gave my copies of these to a little girl - I didn't foresee that I would later want to fondly regard then as an essential part of my permanent collection.

Then there followed that remarkable pair of books, Fungus The Bogeyman (1977) and The Snowman (1978). They have little in common but they will always be a pair in my mythology because they so perfectly illustrate the expressive potential of the comic-strip vocabulary. Fungus is a mad, messy heap of a book. A gorgeously baroque extravaganza of mucky detail, down to the foot notes below panels explaining the impenetrably opaque grittiness of the dialogue: "Boilbye, sourheart" (inscribed in Fungus' balloon as he kisses his wife) "Boilbye: corruption of 'Boils be with you" (footnote under the panel). Huge crumpled sheets of text descend in front of pictures to explain details that they almost obscure while doings in this wonderfully anarchic book, coloured in a sickly palette of greens and grays. Fungus Junior sleeps in an unwashed sardine can. Noses run. Earwax accumulates in every corner of every page. Everything is rendered by hand: every colour applied in a fussy-coloured penciller dribble watercolour.

And then there is The Snowman, all crystalline blueness of snow and rosey pinkness of chee, and not a single word in the entire silent 32 pages. Are the poles of the expressive potential of the comic strip anywhere better demonstrated than in these two books side by side? A swift reference to the excellent bibliography of his works at the back of Blooming Books shows Briggs' output between 1973 and his promised book for 2004, The Puddleman, to be only 16 titles. That's approximately two years work per book, and it shows in the craftsmanship.

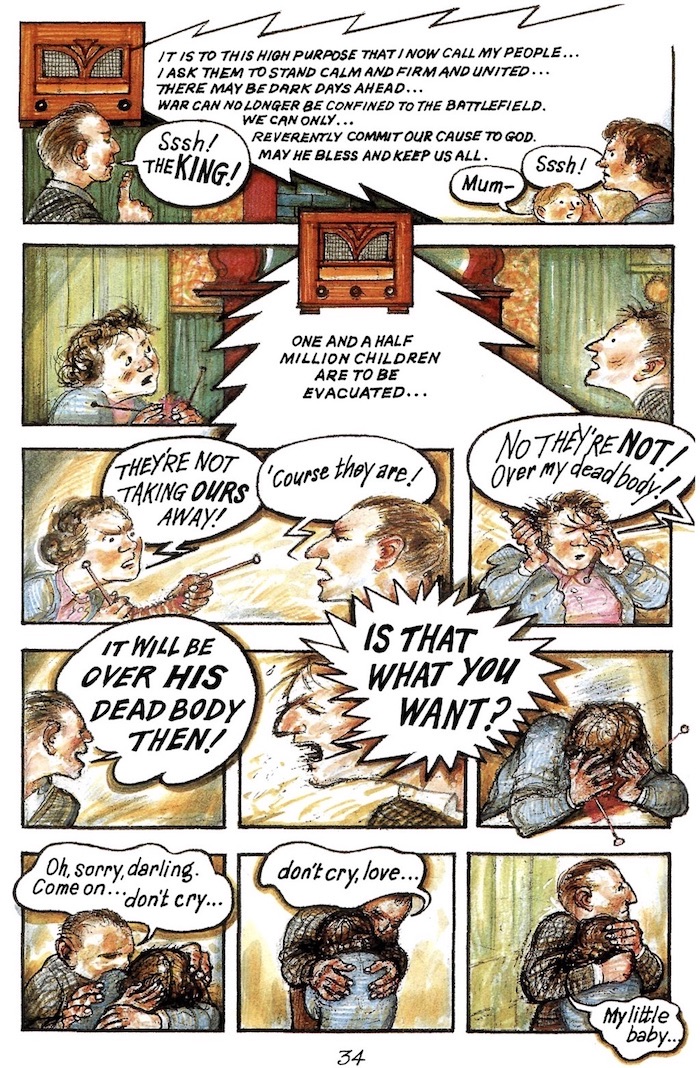

With When The Wind Blows (1972) we have a work that still adheres to the physical dimensions of the illustrated children's storybook, which is to say the hardcovers and full-colour pictures. But the work is unequivocally aimed at an adult reader, although Briggs, like all the great children's authors, was never "writing down" to the kids in his earlier books. It wouldn't surprise me to find that he wasn't actually aware that he was pitching this one to a different readership at all. The simple and trusting Jim and Hilda prepare for the coming nuclear bombardment by attending to the information in the government's official instruction manuals, which, as Briggs demonstrates in his narrative with actual quoted passages, were criminally inadequate. The book fits its time perfectly and became a cause celebre. Britain had found itself with a horribly aggressive government (the Falklands war had been fought that year) and there was a swelling ground level of objection exemplified by the activities of The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The book was adapted as a radio play, a stage drama and then an animated film. Looking at the 15 pages of the original book that are reproduced here (allowing for six reduced very small) we see that Briggs has cranked the contrasts up a few more notches. The pages now have six tiers instead of the four he used for the Father Christmas books, giving us between 20 and 24 tiny pictures per page, building to the explosion, a huge, white, flinging double-page spread. In a recent interview he said he got the idea for the tiny pictures when he saw a reduced sized foreign edition of Father Christmas. He hadn't realised panels could be so small and still work.

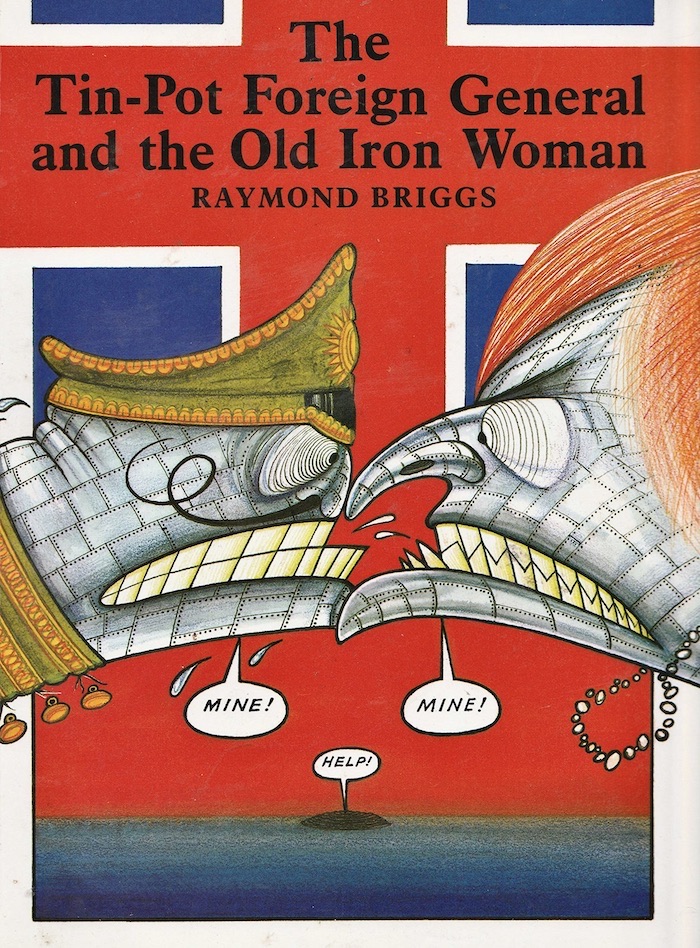

Briggs took his new found role as satirist seriously, and took on Prime Minister Thatcher herself in the next book, The Tin-Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman. This one puts the small panels aside to follow the traditional style of children's illustrated books more closely, which makes satirical sense as Briggs describes the the horrors of the Falklands War as though he were writing a primer. It was an unusual style for him altogether, with its wickedly vigorous caricatures of the two principal combatants, Thatcher and Galtieri. This contrasted with the sensitive and humble pencil drawings of the victims of the conflict, the returned amputee servicemen.

In the year following the publication of this book, I was living in the same town as Briggs and I am sure our paths would have crossed eventually if Fate had not dragged me off to another country. He used to teach illustration at the Brighton College of Art. The Escape Magazine guys [Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury] did a great little interview with him, and came round to my apartment afterwards for a cup of tea. There was a moment there - maybe it last a couple of years - when boundaries fell away and I thought of Briggs and myself (and all sorts of other folk) as working in the same field. This was demonstrated by the fact that when one of the major British newspapers, The Sunday Times, ran a competition to acquire a running comic strip for itself, Briggs sent in samples, just as I did, and probably everyone else I was associated with at the time. At this late stage I can't remember whether they got a permanent strip out of the exercise, but I remember seeing Briggs' samples, which were run in another British paper, The Guardian. It was great to see him thinking of himself as a newspaper strip cartoonist for a few brief weeks, and working in sharp, black line too. There seemed to be an arrival at a peak of sorts, after which things were not to be quite as they had been before.

For some reason Briggs appeared to lose interest in working within the comic strip form. His next four books go all the way over to the old style of children's books. In The Man (1992), text and image are kept quite separate from each other. Where balloons are used, they have set type in them. The Bear (1994), which is about a little girl who is visited by a huge polar bear at night in her bedroom, has more direct passages in it, and some gorgeous coloured pencil drawing in a reprise of the Snowman style. But it still has the type, and at any rate is perhaps most obviously and intentionally a child's book out of all Briggs works after Father Christmas. This is not to say he had reverted strictly to being a maker of books for the kids, although these two may have been a response to editorial urging after the curious pair that preceded them.

Unlucky Wally (1987) and Unlucky Wally: Twenty Years On (1988) are something of an anomaly in Briggs' oeuvre. I am amused to see them dealt with in a somewhat embarrassed and peremptory manner in Blooming Books. Here they are given the least space of all his works and are described as his "least commercially successful." Briggs' former editor, Julia McRae, by that time publishing under her own imprint, offers that if she still had been his editor she would have steered him clear of these self-indulgences. I have the first of them (I was offered the second for a couple of bucks but declined. I now wish I had it here for completions sake and perhaps because the first one is starting to grow on me.) It is, in short, a 48-page exercise in self-loathing. Poor obnoxious Wally is plagued by boils, dandruff, haemorrhoids, blackheads, whiteheads, varicose vines, bad breath, foul bowels, false teeth, flatulence, a runny nose, ad nauseam (literally). A scene that shows him failing his army medical shows him in a room full of burly tattooed naked men at the exact moment the doctor holds his testicles. The only forward movement in the action is the punch line on the final page, to the effect that his mum and dad think he's wonderful. When accused of being too hard on this poor loser, Briggs response was that he was only ever talking about himself. However, since the catalogue of maladies is one that could hardly by sustained by an individual, I suspect that he intended to take us all down with him. A similar incident occurs in The Man with an outpouring of racist slurs that apparently the editor requested by trimmed down. The editing only succeeded in removing the magnanimity of all-inclusiveness.

I do not intend to imply there is an inherent superiority in comic-strip technique over traditional illustration. I have evolved well beyond the stage of defending the comic strip in principle. But we see in the early book about the elephant (The Elephant and the Bad Boy, 1969) a reaching for a kinetic visual language to integrate all the parts. We see the artist casting about for a system that will increase the sense of movement rather than fragment it in the way that looking alternately to a writer's text and then at an artist's image does (and even at that the images are in two modes, colour and monochrome). Father Christmas is not a superior work because it employs comic strip technique, but rather because it succeeds in integrating all of the parts of Santa Claus' universe into a magical night ride. That it uses comic strip technique to achieve this is a secondary consideration. That the later books inspire less of our affection has less to do with the abandonment of this technique than with the overall feeling that creative directional thrust has been weakened. On the same principle, I do not mean to assert that a work is superior because it addresses an adult rather than a child. Briggs' work will perhaps never impress me more than the first time I saw Father Christmas.

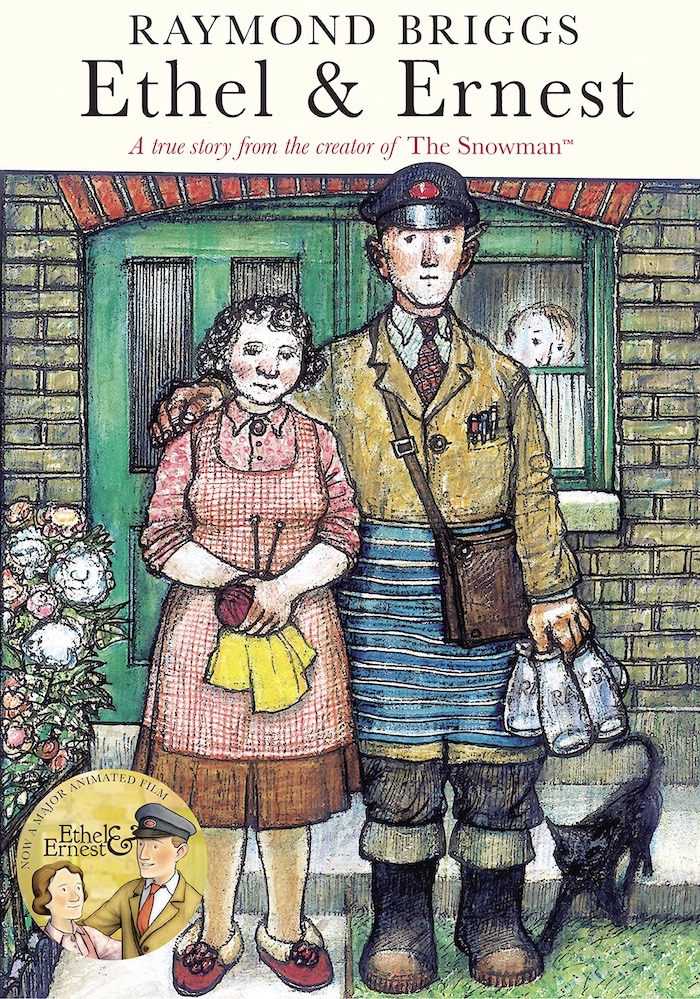

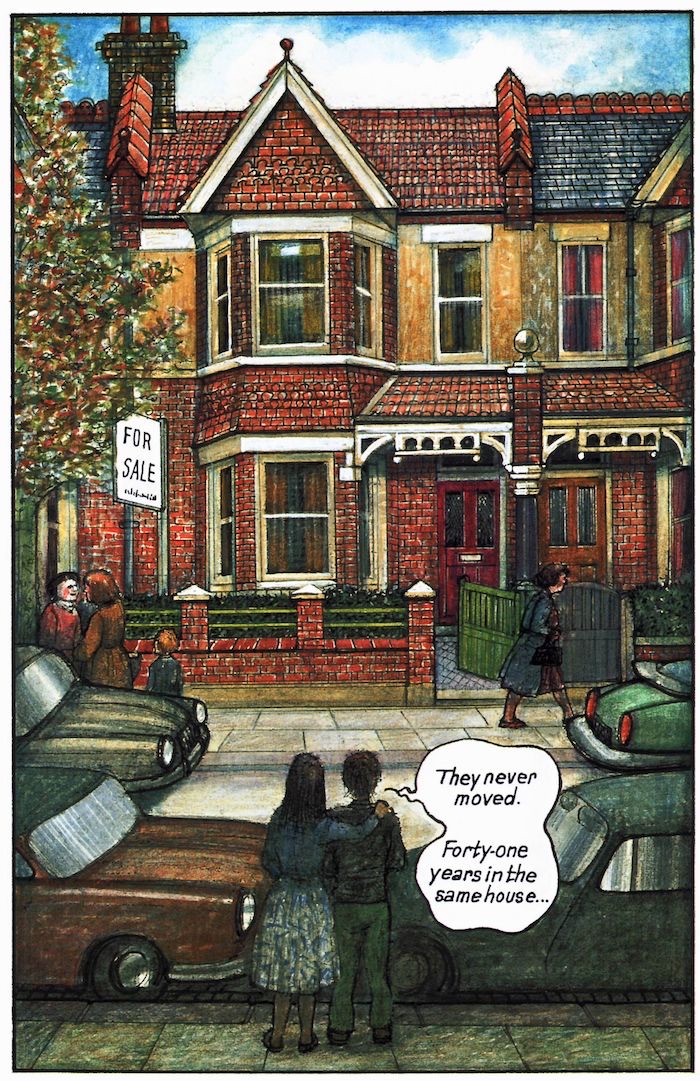

In spite of the above mentioned curiosities, Briggs returned triumphantly to the pure comic-strip idiom with Ethel & Ernest (1998). He has had one self-penned book published since then, being Ug: The Boy Genius of the Stone Age (2001). While it is in the grand old Briggs style that was established from Father Christmas on, it is a slim achievement compared to Ethel & Ernest and I would prefer to end with remarks about that one. Published when he was 64, it was a supreme capping of a great career, a masterpiece in any medium. It would be unfair of us to ask him to go higher than that. It is a biography of his parents and at the same time an account of their times, seen through the particularity of their world view. Briggs himself is in it, of course. The scene of him viewing his mother's body in the hospital is almost too moving to look at. The artist fastens upon the distressing detail of the can of industrial scouring preparation located on the table beside the trolley on which the body rests. Blooming Books give us a striking juxtaposition. The very same trolly with the same cleaning preparation occurs in Unlucky Wally: Twenty Years On. ("Cheerio, Mum" mumbles Wally) showing the unanticipated extent to which autobiography has been a constant in the oeuvre of Briggs. (And giving me another annoying reminder that it's the one Briggs book I haven't read.).

I have often wondered to what extent Briggs is aware of the rest of the universe of comic books and the "graphic novel". For instance, in casting our eye over the field of the last twenty years, we would notice that autobiography has become a magnetic pole of sorts, attracting a number of cartoonists who have already made their mark in other Idioms to take their turn at carrying the standard. Art Spiegelman is the obvious example. The question arises as to whether Briggs had become or had been made familiar with the work of the New York artist. Though its true that correspondences in the work of widely situated artist can occur through the most unlikely coincidences, that separate examples of such high aspiration should occur in the unlikely form of the comic strip without some awareness stretches incredulity. Both artists bare themselves rather painfully with regard to the deaths of their mothers. I would like to believe that Briggs was knowledgeable of this and other events transpiring in the field of the "graphic novel" as it was now being called. It's difficult otherwise to imagine him driving at a work as complete and true as Ethel & Ernest without some knowledge of the movement. But he does not tend to mention these things on the odd accession we read his words directly. That may simply be due to the feeling that the magazine interviewing him may not be au fait with the general facts and major players, a feeling usually confirmed when the interview sees print. I was once dismayed to see words of my own in print as "George Ignatz of Pogo and Krazy Kat fame". It can be better to steer clear of such details.

Another matter that I should like to investigate, if I ever find myself in the interviewer's position, is the extent to which Briggs and Posy Simmonds have been mutually aware. Posy, as you know, or should know, is a newspaper-strip cartoonist whose work has always had a sophisticated adult orientation, and who drifted into children's books using a remarkably similar approach to that of Briggs. Her book Fred was published in 1987 and Lulu and the Flying Babies in 1988. I haven't seen he former, but the latter owes a great deal to the Briggs style, with its delicate pencil colouring and hand lettered balloons. It is surely significant that in her book of 1994, Bouncing Buffalo, she has turned more toward a conventional children's book style, with large pictures and separated text. In other words, both Briggs and Posy have compromised their "strip" approach in the same period and in books from the same publisher. One would have to ask if this was the result of an editorial directive, and if so, whether it was a result of the changing fortunes in the life of the graphic novel. The book market has had a love affair with it starting in 1986 but by the end of the decade things had taken something of a downturn. There would be another turnaround before the end of the nineties and both Briggs and Posy played a roll in the revival, with Ethel and Ernest and Gemma Bovery respectively. But I should like to know how much of this pattern was visible to the participants. It would be useful information in helping us to think about the formation of the graphic novel as owing something to the coming together of strands from different outposts of graphic art, from newspaper strips, children's books, and the underground and small-press movement within the comic-book field.

Much is made in some quarters to demonstrate that Briggs' work "is comics", what ever that may mean (the opinions of the nincompoop brigade - McCloud, Harvey etc - tend to obfuscate more than they illuminate). The aficionado of the comic books sees himself as belonging to a confraternity not dissimilar from a brotherhood of mutants. To this type, it is not enough to characterise Briggs as an illustrator who borrows the techniques of the strip cartoonist. It must be further demonstrated the he is or is not of the true gene. In the intro to Blooming Books by Jones: "Briggs, who went to bat for students he believed in... whose work he admired and who happened to be cartoonists." (Indeed, the secret marks by which we recognise our own.) Briggs, in his latter-day comments, has started to adopt the traits of the initiate and to defend the form at the drop of a hat. In this mode he tends to sound rather whiny, as in the article quoted above: "Why I'd like to be a proper author" - subtitled "Strip cartoons are a botheration for Raymond Briggs" - from The Guardian (November 2, 2002), which you may be able to locate online. "I wish I could be a proper writer, having to do only the words. Proper writers can start at the beginning, go on til they get to the end, then stop and hand it in. No drawing and painting, no design, no jacket to do and, above all, no hand lettering. Luxury." The intended effect is probably to invoke the personality of that endearing curmudgeon, his own, Father Christmas, but I do not warm to it. Perhaps I have spent too long trying to create the impression of a vigorous and unapologetic artistic movement to allow room for other voices. If it turns out that Briggs in fact identifies, at a deep level even, with the comic-book aficionado in all of his supposed emotional insecurity and maladroit unhealthiness, then it's time to go back and reexamine the two Unlucky Wally books. We might hear what we missed the first time around when we weren't listening properly.

Eddie Campbell is the celebrated creator of Alec and Bacchus, and collaborator (as artist) with Alan Moore on From Hell. His recent book The Goat-Getters explores the early years of the newspaper strip.

No comments:

Post a Comment