by Dave Sim & Will Eisner

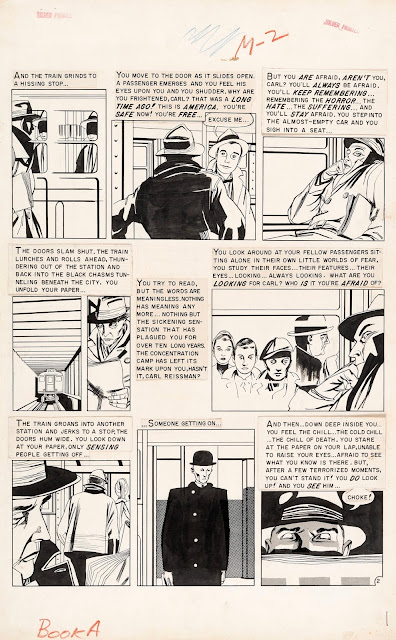

I remember first seeing Will Eisner's The Spirit in The Penguin Book of Comics when I was about 13 or 14 years old. The experience was a memorable one because The Spirit was so obviously neither fish nor foul. Structurally it was far more a comic book than a comic strip but it had appeared in newspapers, which only comic strips did. Because I was so firmly a devotee of comic books and only marginally interested in comic strips, the impact that first exposure had on me was notable. The writer, as I recall, was terrifically enthusiastic about the material. I do remember that. This was back in the days when the few books that were written about comics were all about comic strips - books where Superman and Batman were dealt with as peculiar outgrowths of a second-, if not third-rank comic strip mutation. So, I first knew Will Eisner as the comic book artist that comic strip fans enthused about.

Later I would read Jules Feiffer's groundbreaking seminal work on the comic book, The Great Comic Book Heroes, with his even more effusive enthusiasm for Will Eisner and The Spirit. There was a political schism between Feiffer and myself - he favours the early prewar Spirit while I'm more partial to the later studio work of 1946, 1947 and 1948.

What comes home to me in typing that simple observation on dichotomous preferences is that - while we are separated in age by decades - Feiffer and I both met Will when we were barely out of childhood and grew into full adulthood under his watchful (and here's the core of my point) non-patronising overview. It would have been far from inappropriate for both of us to have been patronised by Will Eisner. Whether in 1948 or 1974, who could match Eisner for stature, for influence and for sheer longevity? Yet I never saw him behave in a patronising fashion towards anyone - he never so much as betrayed a glimmering of amusement at the inescapable fact that even the most senior members in the field were, in one sense or another, newcomers and novices in comparison to himself. He could look at Joe Kubert, for heaven's sake, and say, "Oh, right. I hired him to sweep the floors."

Will and I and so many others shared a profession and an all-consuming interest in the graphic narrative and an abiding faith in its limitless possibilities. That was all that it took to be treated as a peer and a contemporary by Will Eisner. If you cared deeply about the narrative form he cared most most about, he cared about you - and usually in direct proportion to your own level of devotion to the comic-book medium. In retrospect, it's not hard to see why, given that he had carried that profound level of faith in comic books across decades - virtually single-handedly and in the face of virtually universal disdain and derision (no one thought that the comic-book medium was as important as he though it was as early as he had thought it was and for as long as he thought it was). He carried the medium from obscurity and vituperation to acceptance and celebration...

...it's unthinkable what he accomplished.

I mean, it is literally impossible to retain an accurate mental image that encompasses, simultaneously, all of the many varied parameters and depths of his comic-book life and his comic-book career that was lived and conducted on the monomaniacal footing and scale that it was.

Nearly seven decades.

He invented and then refined most of the key components of the intrinsic language of the comic-book page over the course of a decade before anyone even recognised that there were components. He was the first comic-book creator on weekly display before a general interest audience (and 60 years later that's still a claim which is his alone!). He was there as an active participant in the birthing of the form itself and at the cusp on the medium's greatest financial success - when it had become virtually a license to print money and he and his partners jointly owned one of the few metaphorical printing presses which he had carefully assembled, lubricated and tweaked and fine-tuned - he quit what he was doing, walked three steps away and reinvented the medium in such a way that would better serve his creative purposes and interests. As Robert Blake once said when someone remarked on what an odd pair of companions he and Truman Capote made - the tough guy actor and the fey writer - "Don't kid yourself. He's got balls the size of your head."

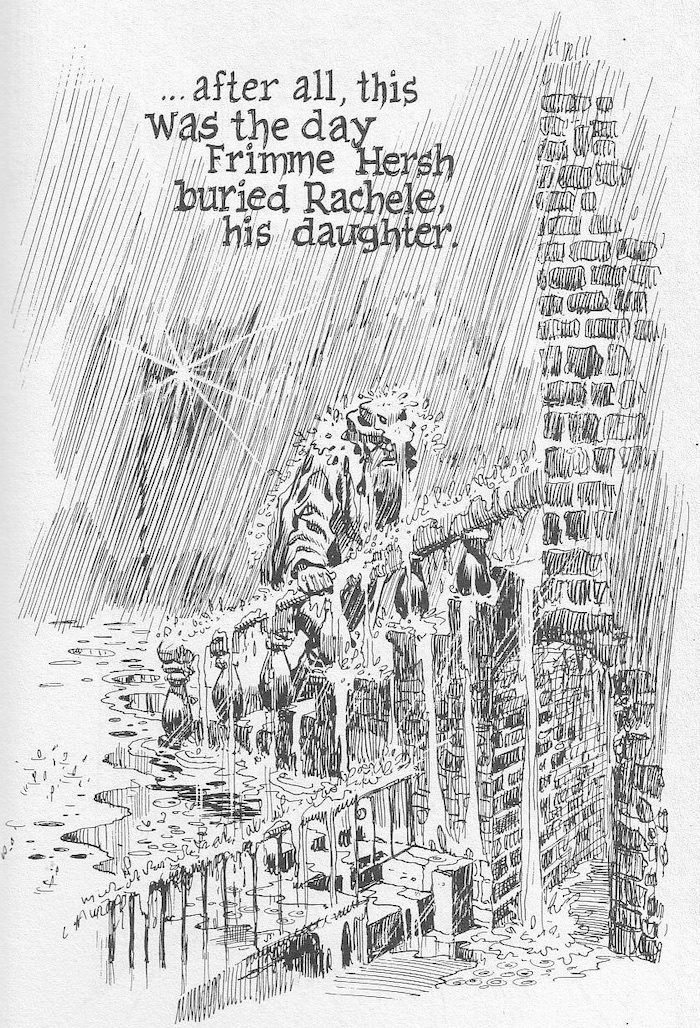

Long before Scott McCloud popularised the phrase as a book title, Will Eisner was Reinventing Comics on a regular basis. The Eisner and Iger Studio was a way of reinventing comics, The Spirit - in terms of form, content and distribution was a means of reinventing comics, P*S Magazine was a way of reinventing comics, the Harvey, Warren and Kitchen Sink reprinting of The Spirit were, each, a reinventing of comics - beginning in the mainstream, proceeding to the periphery and ending up in the rugged outlands of the field. The exact inverse of a careerist approach. A Contract With God was a reinvention of comics as the graphic novel.

I'm not sure the he was too pleased that I considered the title story in A Contract With God to be his highest achievement in the field. With his relentless forward momentum and all-consuming need to produce The Mature Body of Work his newest offering was always the horse he had bet the metaphorical creative farm on. He didn't say it, but I could see it in his eyes:

"A Contract With God? Jeez, Dave, that was 25 years ago. You wait. The next one'll knock your socks off."

I stopped buying his work a few years ago when I realised that there was going to be a finite number of remaining projects that I would, likely, be able to count on the fingers of one hand. The depravation of not being current with his work ran a distant second behind my awareness of what it would be like to know that I'd never read a new Eisner book for the rest of my life. I had learned that hard lesson when I ploughed through the works of Dostoevsky in my 20s.

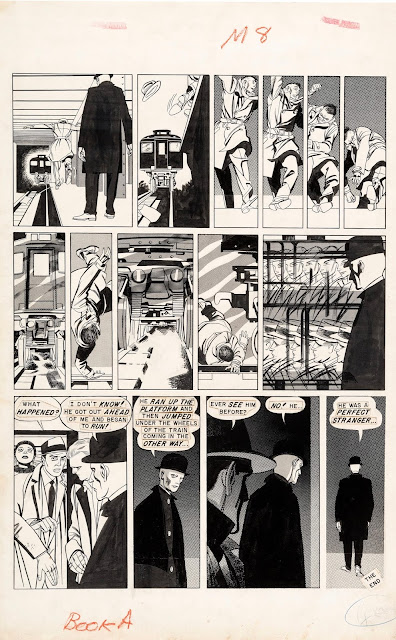

I remember when The Comics Journal printed a review of The Dreamer (was it Gary Groth who wrote it? I seem to remember that it was), sneering at it for its laundered view point of the '30s and the early history of the comic-book medium. It was perfectly brutal - where was the racism, the anti-Semitism the must have been all around and why was Eisner sugar-coating the reality instead of addressing it head-on? It was as much amounted to a bad review of Eisner himself for living too long and retaining too much in the way of discretion and tact and good manners in a world where those qualities were no longer valid. I wasn't alone in bristling on Will's behalf.

But give Will credit: He hadn't come as far as he had over those many years, arriving clear-eyed and lucid in the fourth quarter of the 20th century without having learned how to take a punch. It would never have occurred to him to close himself off to criticism or to be hurt and/or offended by a negative review. He was certainly entitled to do so by virtue of even a fraction of his seniority in the field, but he recognised that to walk that road would mean a living death if he allowed himself to retreat behind (what would undoubtedly have been) an impregnable wall of sycophancy.

As I recall Dropsie Avenue was the result. I ran across it the other day - it had been misplaced among my personal papers - and flipped it open, just intending to refresh my memory. 15 minutes later, I gave in and retreated to my room to read it in its entirety. The Jews were called hebe. The Italians wops. The Irish micks. And for the first time in an Eisner work, the motivating force of pure hatred and malice was moved to the forefront of the narrative, there to contend with, interweave and serve as a counterpoint to the higher aspirations of individual human beings which were Eisner's first and most genuine creative interest.

It was just another inconceivable facet of the multifaceted Mr. Will Eisner. In what other medium has anyone who has attained to the stature of living legend continued to be - not only open to criticism - but responsive to it? At a point where the years remaining in his creative life had dwindled to precious few, Eisner was amenable, with perfect equanimity to allow for the fact that his entire approach and execution on The Dreamer - which had taken up the better part of one of those few remaining years to complete - might have been a mistake and he was capable, again with perfect equanimity, of rethinking his approach from the ground up the next time out. His reputation in the avant garde took an awful beating, but everything was a learning experience for Will, everything was just grist for the mill.

For years, I thought it was unfortunate that there was never a magazine which reflected Will's sensibility the way that The Comics Journal reflects our medium's Other Awards Namesake, Harvey Kurtzman's (more Kurtzman's sensibility as filtered through Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman, but that's a subject for other time...) But reading Dropsie Avenue and remembering the creative, intellectual and visceral response that it represented I think things probably worked out for the best. A magazine that reflected Eisner's sensibility wouldn't have been able to provoke him into moving his work to another level and rethinking his approach that late in life. Will never wanted to be insulted from anything, least of all honest criticism. Ultimately, that was the source of his inclusiveness that left amateurs and professionals agog in his wake at the many conventions that he attended. There was only one playing field as far as he was concerned and it was completely level, with everyone contending for the same disposable income on the same comic-store shelf. He was more than happy to treat you as a peer and a contemporary if you were willing to extend him the same courtesy - to treat him as a peer and a contemporary and not just a living monument to be photographed next to. And if Frank Miller and Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman regularly kicked his ass in the sales department, mentally, inwardly he was always grinning from ear-to-ear and saying to them...

"You just wait. The next one'll knock your socks off."

Will Eisner (1917-2005) was a comics pioneer and creator of The Spirit, A Contact With God, To The Heart Of The Storm, Dropsie Avenue and many other stunning graphic novels. The Eisner Awards are named in tribute to his influence on the comics medium.

Dave Sim is the creator of Cerebus The Aardvark, a groundbreaking, 300-issue, monthly, self-published comic, which he completed with background artist Gerhard, between 1977 and 2004. This essay first appeared in The Comics Journal #267 in 2005.