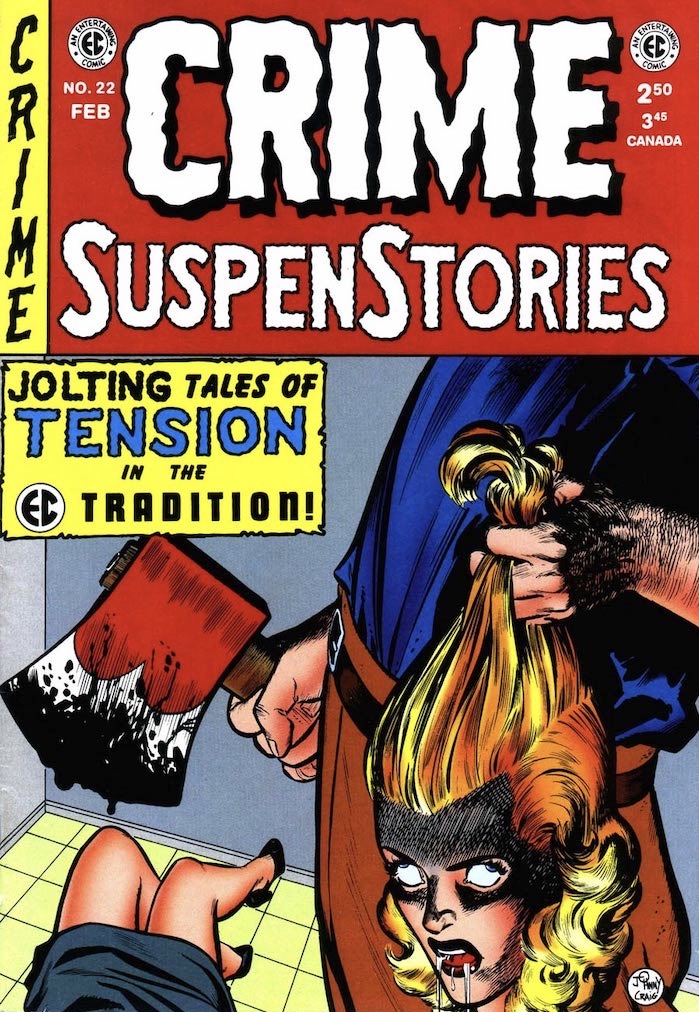

edited by Harvey Kurtzman, with Wally Wood, Bill Elder, Jack Davis and others

REVIEW BY DARCY SULLIVAN:

Despite their very name, comics have contributed very little to America's comic legacy. Comic strips have introduced many of the most famous persona of American humour, from Charlie Brown to Zippy to Ziggy. But strip away the obscurities (including all alternative comics), the borrowings from other media and the juvenilia, and only one comic book emerges as a true influence on the country's comic consciousness: MAD.

MAD has been an American institution for more than 40 years. Even kids who skipped the Superman and Spider-Man phase snuck MAD to school, memorised the zany names given to characters from films (even films they'd never seen), compete to see who could most adeptly manipulate the back cover fold-in.

The MAD honoured here, however, prospered for just four years, from the comic's birth in 1952 until 1956, when its father, Harvey Kurtzman, left its publisher, William Gaines' EC Comics, in one of the classic creator's rights disputes in comics history. (Shades of Image: Kurtzman not only left MAD, he took his top artists with him and started his own humour magazines.)

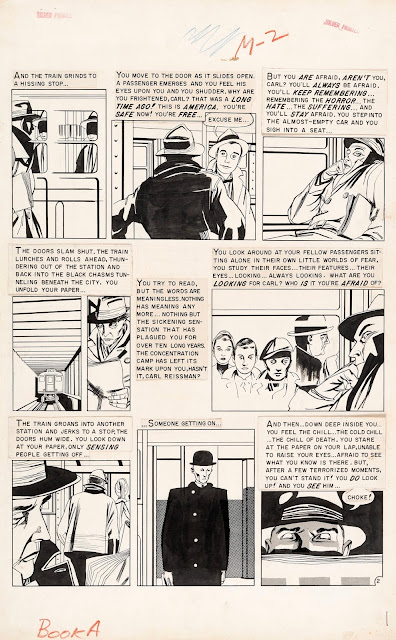

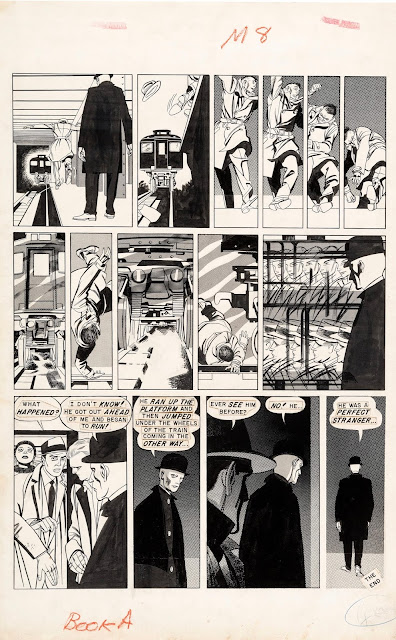

Kurtzman possessed a fluid, rhythmic drawing style suited to physical humour. He was also a detail obsessed writer, who had rewritten the rule book on war comics on EC's Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat. As Kurtzman saw it, he was a seeker of Truth.

Of course, a few bucks wouldn't hurt. Kurtzman wanted a book he could crank out faster than his heavily researched war comics. He proposed a humour magazine to Gaines. In its first incarnation MAD was a comic book about comic books (postmodernist alert!) - largely poking fun at the kinds of comics that kept EC afloat.

MAD quickly ran out of comic books to lampoon and began taking on other media, particularly film and advertising. And in a stroke that still seems revolutionary, Kurtzman persuaded Gaines to publish MAD in magazine format - thus sidestepping the then raging furor over comic books and giving Kurtzman the "status" book he sought (he'd been wooed by a major magazine of the day, Pageant).

Notoriously strict about artists following his breakdowns, Kurtzman is clearly MAD auteur. But the artists who drew it - especially Wally Wood, Bill Elder and Jack Davis - rose to the occasion, introducing a new freneticism to comic art. They squirted panels full of sight gags and non sequiturs, creating a dense style described as "chicken fat". That manic energy, along with Kurtzman's rapid-fire verbal riffing, made MAD's pages absolutely electric and immediate.

Critics have praised MAD so fulsomely that the magazines true historical impact has been distorted. Neither Kurtzman or MAD created American satire - but they did bring it to a younger audience. Kurtzman and company used humour as a crowbar to pry apart what things were and what they pretended to be. "Just as there was a treatment of reality in the war books," Kurtzman wrote in his comics history From Aargh! to Zap!, "there was a treatment of reality running through MAD; the satirist/parodist tries not just to entertain his audience but to remind it of what the real world is like."

Ultimately, though, Kurtzman and MAD's subsequent writers were part-time satirists and full-time funnymen. Like children, they would make fun of anything - left or right, young or old, good or bad - simply because it was there. Gaines would later argue that MAD had no morality, no statement beyond "Watch out - everybody is trying to screw you!" Satire was important to MAD, but its real metier was iconoclasm. It was a pie chucked at the nearest face visible.

And like the pie in the face, it was both anarchic and quaintly traditional. Kurtzman brought the Jewish inflections of Catskills comedy to comic books - what are MAD coinages like "potrzebie" and "veedlefetzer" if not put-on Yiddish? Kurtzman's joke constructions drew frequently and expertly from vaudeville comics. The balance between deconstructive cliche-busting and well-structured routines, between Swiftian wit and pure spitball silliness, helps account for Mad's sustained and wide-ranging popularity. For all its buzzing surface quality and apparent rudeness, MAD wasn't nasty - it had charm.

MAD's historical importance grew in the 1960s and 1970s, when it offered the pre-protest set their own connect-the-dots guide to social criticism. And many of MAD's most famous conventions - the movie parodies with Mort Drucker's deadly caricatures, the gonzo visual slapstick of Don Martin, the witty wordless rim-shots by Sergio Aragones and Antonio Prohias - post-date Kurtzman's reign as well. But these and other riches simply wouldn't exist without Kurtzman and his original collaborators, who created MAD's skewed, sarcastic, staccato style. Godfather of the undergrounds, influencer of modern film humour, infiltrator of virtually all media, Kurtzman's little "quickie book" stands not just as one of the greatest comic books ever, but as a true cultural phenomenon.

REVIEW BY ALAN MOORE:

(from a tribute to Harvey Kurtzman in The Comics Journal #157, 1993)

The first time I encountered Harvey Kurtzman, I was around ten years old. The encounter took place between the covers of The Bedside MAD, a paperback collection; strange, American, the cover painting possibly by Kelly Freas, the edges of the pages dyed a bright, almost fluorescent yellow. To this day, it burns inside my head. The stories in that volume and the Kurtzman stories I discovered later brandished satire like a monkey-wrench: a wrench to throw against pop-culture's gears or else employed to wrench our perceptions just a quarter-twist towards the left, no icon left unturned.

REVIEW BY DAN CLOWES:

Had he not existed, I'd be a dull, humorless lout working in a muffler shop somewhere, and so would practically everyone I know. I shudder to think how horrible the world would be today without that which Harvey Kurtzman begat!

REVIEW BY BILL GRIFFITH (ZIPPY THE PINHEAD)

MAD was a life raft in a place like Levittown, where all around you were the things that MAD was skewering and making fun of. MAD wasn't just a magazine to me. It was more like a way to escape. Like a sign, This Way Out. That had a tremendous effect on me.

FURTHER READING: