Interestingly, Krazy Kat gains its momentum less from the personalities of its characters than from their obsessions. Ignatz Mouse demonstrates his contempt for Krazy by throwing bricks at her; Krazy reinterprets the bricks as signs of love; and Offissa Pupp is obliged by duty (and regard for Krazy) to thwart and punish Ignatz's "sin," thereby interfering with a process that's satisfying to everyone for all the wrong reasons. Some 30 years of strips were wrung out of that amalgam of cross-purposes. The action can be read as a metaphor for love or politics, or just enjoyed for its lunatic inner logic and physical comedy.

Despite the predictability of the characters' proclivities, the strip never sinks into formula or routine. Often the actual brick tossing is only anticipated. The simple plot is endlessly renewed through constant innovation, pace manipulations, unexpected results, and most of all, the quiet charm of each story's presentation. The magic of the strip is not so much in what it says, but in how it says it. It's a more subtle kind of cartooning than we have today.

To the bewilderment of many readers, there are few endings in Krazy Kat that qualify as "punchlines." Instead, it's the temperament of the writing and drawing throughout the strip that is the joke. If you don't think it's funny that a strip should have an intermission drawing, or that a character would refer to his tail as a "caudal appendage," you're reading the wrong strip, and it's your loss.

Quirky, individual, and uncompromised, Krazy Kat is one of the very few comic strips that takes full advantage of its medium. There are some things a comic strip can do that no other medium, not even animation, can touch, and Krazy Kat is a virtual essay on comic strip essence.

In their headlong rush for the "gag", most cartoonists run right past the countless treasures Herriman uncovered simply by taking his time to explore the freedom of his medium. The self-consciously baroque narrations and monologues ("From the kwaint konfines of the kalabozo del kondado de Kokonino -- Officer 'Pup' gives answer") show that words can be funny in themselves, just as drawings can. The sky turns from black to white to zigzags and plaids simply because, in a comic strip, it CAN. No other cartoonist ever approached his blank sheet of paper with so much affection for all its possibilities.

The scratchy drawings delight me no end. They have the honesty and directness of sketches. So many of today's strips are slick and polished, the inevitable result of assistants trying to develop a mechanical style that can be continued indefinitely. The drawings in Krazy Kat are whimsical, idiosyncratic, and filled with personality. The bold design of the Sunday strips neatly compliments the flat expanses of color or black, and the wonderful hatching brings character to the otherwise posterish approach.

Nothing in Krazy Kat had a supporting role, least of all the Arizona desert setting. Mountains are striped. Mesas are spotted. Trees grow in pots. The horizon is a low wall that characters climb over. Panels are framed by theater curtains and stage spotlights. Monument Valley monoliths are drawn to look more like their names. The moon is a melon wedge, suspended upside down. And virtually every panel features a different landscape, even if the characters don't move. The land is more than a backdrop. It is a character in the story, and the strip is "about" that landscape as much as it is about the animals who populate it.

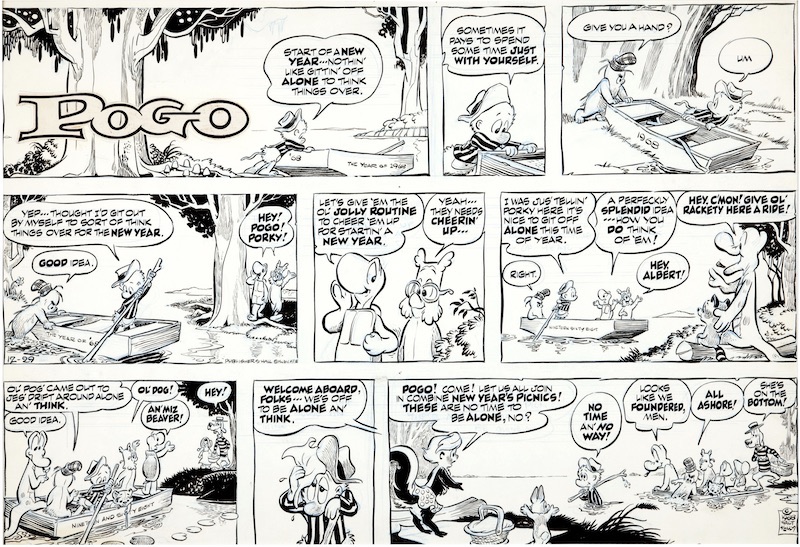

As the artwork is poetic, so is the writing. With the possible exception of Pogo, no other strip derives so much of its charm from its verbiage. Krazy Kat's unique "texture" comes in large part through the conglomeration of peculiar spellings and punctuations, dialects, interminglings of Spanish, phonetic renderings, and alliterations. Krazy Kat's Coconino County not only had a look; it had a sound as well. Slightly foreign, but uncontrived, it was an extraordinary and full world.

Darn few comic strips challenge their readers anymore. The comics have become big business, and they play it safe. They shamelessly pander to the results of reader surveys, and are produced by virtual factories, ready-made for the inevitable t-shirts, dolls, greeting cards, and television specials. Licensing is where the money is, and we seem to have forgotten that a comic strip can be something more than a launchpad for a glut of derivative products. When the comic strip is not exploited, the medium can be a vehicle for beautiful artwork and serious, intelligent expression.

Krazy Kat was drawn well over half a century ago, and yet it's a much more sophisticated use of the comic strip medium than anything we cartoonists are doing today. Of course, a 1930s Sunday Krazy filled the entire newspaper page, whereas editors today usually cram at least four strips in the same amount of space. This reduction of size greatly limits what can be drawn and written and still remain legible, and it goes a long way toward explaining the comics' devolution.

Even so, the whiteness of paper is still vast, uncharted territory, ripe for exploration. There are plenty of exotic lands for a cartoonist to map, if he or she will leave the well-worn paths and strike off for the wilds of the imagination. Krazy Kat is like no other comic strip before or after it. We are richer for Herriman's integrity and vision.

Krazy Kat was not very successful as a commercial venture, but it was something better. It was art.

Bill Watterson is a cartoonist and created Calvin & Hobbes. Fantagraphics Books have reprinted George Herriman's complete Krazy Kat Sunday pages (1916-1944), which belong in any serious comics reader's collection.