Diastrophism, especially as collected in Blood of Palomar, represents the culmination of Gilbert's series Heartbreak Soup, set in the mythical Central American village of Palomar. Echoing the first story in that series, Sopa de Gran Pena (1983), which established such characters as Luba and Heraclio, Diastrophism also distills the best of Hernandez's work in-between. The fluid sense of time and memory found in The Reticent Heart, the dizzying simultaneity of social life in Ecce Homo, the violence and social upheaval shown in Duck Feet - these elements converge in Diastrophism, as a serial murderer stalks the streets of the town, forcing a long-delayed confrontation with the outside world.

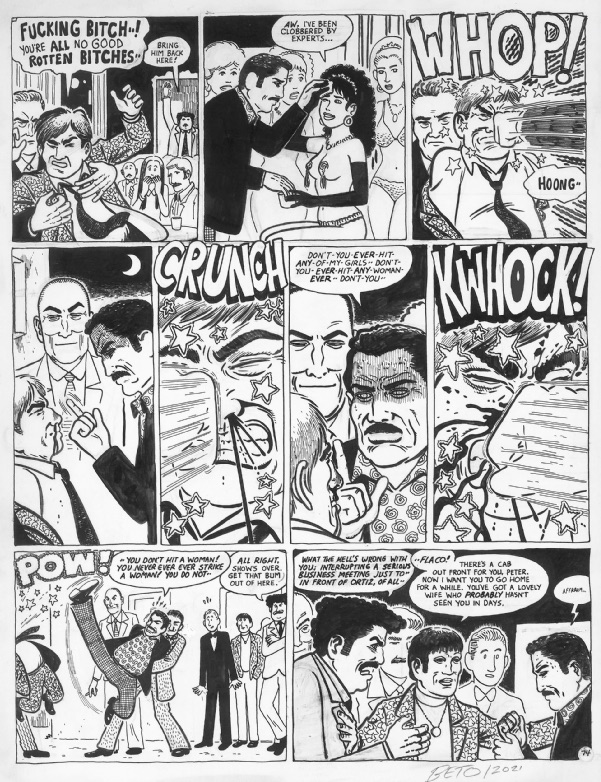

The killer turns out to be a native son, returning to the nest; other characters, ironically, end up leaving Palomar, some never to return. When the dust is clear, even those who remain face diastrophic (ie earth-shaking) changes in their lives, and must acknowledge things about themselves that they never knew. These people seem real: the finely-tuned dialogue and loose, energetic cartooning join to achieve a rare depth of characterisation. Gilbert's repertory company, dozens strong, gives the novel a richly human texture.

Palomar emerges as a distinct if volatile community, a social arena defined by deep, multi-plane compositions and a roving, restless eye. Throughout, Gilbert expertly manipulates the formal rhythms of his storytelling to capture the town's mounting hysteria: transitions become increasingly abrupt, sequences increasingly dense, as Palomar goes to hell in a hand-basket. This trend climaxes in a tour-de-force, in which the village, dubbed "ground zero", explodes with frantic activity. In the midst of all this, familiar characters like Luba emerge more sharply etched, complicated and intriguing than ever before.

At storm centre, Hernandez positions a new character named Humberto, an aspiring young artist whose work is informed, indeed, transformed, by his complicity in a brutal act of violence. Witness to the disintegration of the town, and privy to the secret of the killer's identity, Humberto goes from eager observer to haunted recluse - confused, nauseated, eyes limned with shadow and pain. His faith in his work - his belief that his artwork will "speak" for him and bring the killer to justice - is naive, arrogant and terribly moving. The book's finale, which pits Humberto's artistic aspirations against an awful, almost incomprehensible loss, has the force of a sucker punch.

To me Human Diastrophism is the great comics novel of the direct market era. When I first read it, in Love & Rockets, I found myself shaking when I got to the end - a response which had something to do with profound pleasure, and something to do with shock. Comics were never the same for me afterwards: the wan pleasures of nostalgia became paler still, embarrassed by the recognition that comics could offer narratives of greater emotional heft, more enticing complexity, and more penetrating social argument. My faith in the form had been rewarded in ways I could not have expected, beggaring all expectations.