It was a misnomer that started it...

In the mid '80s some well-intended journalists and booksellers tried to distinguish a handful of book-format comics from other, less ambitious, works by dubbing them "graphic novels." But even though my own book, Maus, was partially responsible for making bookstores safe for comics, the new label stuck in my craw as a mere cosmetic bid for respectability. Since "graphics" were respectable and "novels" were respectable (though that hadn't always been the case), surely "graphic novels" must be doubly respectable!

It was a wrong-headed notion that started it...

It would take another decade before enough long, ambitious comics gave the concept critical mass - until enough work worthy of critical attention made a bookstore section of some sort inevitable - but, tired of seeing my Maus volumes surrounded by fantasy and role-playing game manuals, I tried to jump-start the process. In the early '90s I groused to one of my editors that if my work was fated to be ghettoized in a graphic novel section, perhaps the neighborhood could be improved by hiring some serious novelists to provide scenarios for skilled graphic artists. I got permission to approach several well-known novelists, including William Kennedy, John Updike and Paul Auster.

It was a number of friendships that started it...

I was fortunate enough to become friends with Paul Auster in the late 1980s, and my repeated cajoling got him to toy with the possibility of collaborating with a cartoonist. He had the glimmering of an idea: a vision of a boy floating above water. Next thing I knew, that glimmer became his next novel, Mr. Vertigo, and he kindly invited me to provide a jacket drawing. All the novelists I contacted were intrigued by my proposal, then fled. (Updike, who early in his career wanted to become a cartoonist, said it had taken him fifty years to finally become reconciled to making his cartoons with words.) Even I was a bit dubious of my own idea, secretly convinced that the "purest" expression of the comics form demanded text and pictures made by one person.

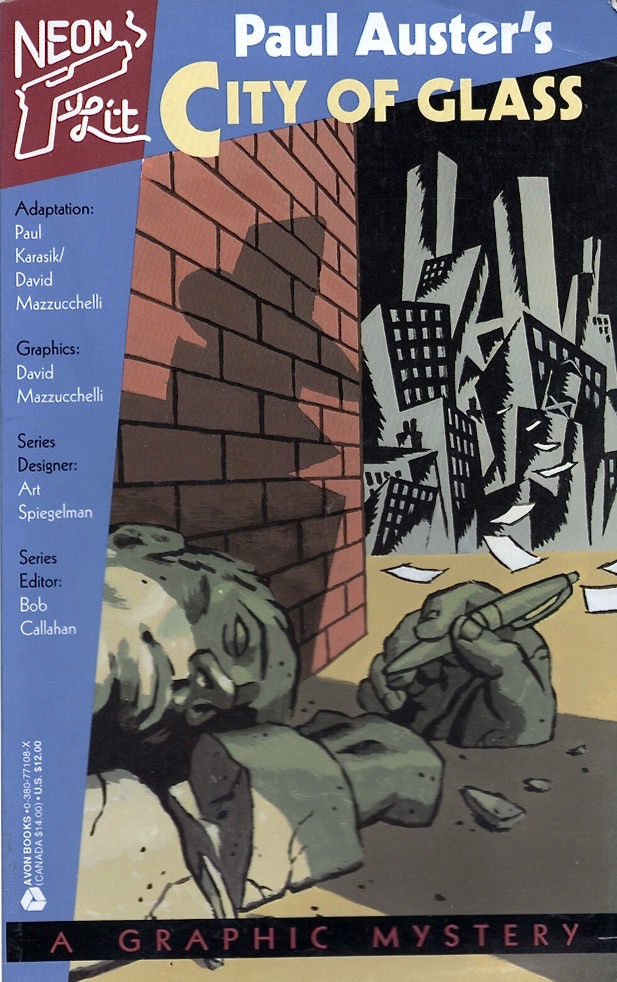

And so the project languished, only to be replaced with what I believed was an even worse idea. At some point Paul had suggested that I simply adapt one of his already published works. I shrugged that off until another friend, Bob Callahan, in turn cajoled me into co-editing a series of books with him: comics adaptations of urban noir-inflected literature. I couldn't figure out why on Earth anyone should bother to adapt a book into... another book! To make the task more difficult, the goal here was not to create some dumbed-down "Classics Illustrated" versions, but visual "translations" actually worthy of adult attention. City of Glass was exactly the sort of novel Callahan was reaching for to define what we eventually called "Neon Lit," but rereading Auster's slim volume made the choice seem downright daunting - and therefore actually worth a shot! For all its playful references to pulp fiction, City of Glass is a surprisingly non-visual work at its core, a complex web of words and abstract ideas in playfully shifting narrative styles. (Paul warned me that several attempts to turn his book into a film script had failed miserably.)

I enlisted David Mazzucchelli, whose art on Frank Miller's Batman: Year One had shown a grace, economy and understanding of the form that made the superhero genre almost interesting. The astonishing avant-garde comics and graphics he then went on to self-publish after abandoning the "mainstream" at the height of his acclaim made him seem ideally suited to the challenge of grappling with our proposed adaptation. But after a number of attempts, David began to look disheartened: he was more than able to tell the "story" in Paul's novel but couldn't quite locate the inner rhythms and real mysteries that made the story worth telling. Maybe it was impossible.

Grasping at straws, I called Paul Karasik who had been a student of mine at New York's School of Visual Arts back in 1981 and 1982 (the very years, it turns out, that Paul Auster was writing City of Glass). As a teacher I had come up with some resolutely implausible assignments - like asking students to turn a rather non-narrative passage of Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury into comics - and Karasik had consistently demonstrated a gift for intelligent, plausible solutions.

After explaining our impasse, I remember him cockily telling me he was born for this assignment, but I didn't hear his Auster-like back-story til much later. It seems that back in 1987 (the year, it turns out, that Paul Auster and I first met) Paul Karasik was teaching art at Packer Collegiate in Brooklyn Heights. Learning that one of his most talented eleven year old students, Daniel, was the son of the novelist, Paul Auster, Karasik read several of his books, and for a lark... broke down a few pages of City of Glass in one of his sketchbooks!

The new breakdown sketches he did six or seven years after that first experiment were inspired. When I got to the pages that captured Peter Stillman's memorable speech to Quinn, my jaw dropped. It was an uncanny visual equivalent to Auster's description of Stillman's voice and movements:

"Machine-like, fitful, alternating between slow and rapid gestures, rigid and yet expressive, as if the operation were out of control, not quite corresponding to the will that lay behind it."

By insisting on a strict, regular grid of panels, Karasik located the Ur-language of Comics: the grid as window, as prison door, as city block, as tic-tac-toe board; the grid as a metronome giving measure to the narrative's shifts and fits.

There was one problem with the sketches: Neon Lit's small final page format couldn't accommodate all those relentless rows of tiny panels without looking uncomfortably cramped. The scrupulous compressions (Paul K had shaped the adaptation so that each cluster of panels took up proportionally about as much space as the corresponding paragraphs did in Paul A's prose original) needed to be rethought so the pages could "breathe" a bit more. Occasional larger images were needed to beckon the reader's eyeballs into the congested grid. Fortuitously, this allowed David back in as a full participant in the further condensing and reshaping whereby he could engage the work with all his formidable skills.

As for Auster, I'm convinced he behaved generously throughout...

Paul Auster, appreciative of the wiggle-room translations and adaptations demand, spent a long, fruitful day with Mazzucchelli, Karasik and I, studying the draft and offering suggestions. Generous as always, he was pleased and supportive, but I don't think he fully realized just how overwhelming the odds against success had been or that his novel had occasioned a break-through work. By poking at the heart of comics structure, Karasik and Mazzucchelli created a strange doppelganger of the original book. It's as if Quinn, confronted with two nearly identical Peter Stillmans at Grand Central Station, chose to follow one drawn with brush and ink rather than one set in type. The volume that resulted, first published in 1994, overcame all my purist notions about collaboration. It offers one of the richest demonstrations to date of the modern Ikonologosplatt at its most subtle and supple.

- art spiegelman 12/31/03