Although Sterrett (1883-1964) changed the strip's title to indicate its broadening focus, even Polly & Her Pals does not reflect the true basis of the comedy - the clash of mores between generations. Paw's exasperated outrage inspired most of the laughter, and he was soon the star of the strip. To wring everything he could from the situation, Sterrett surrounded the old man with a cast of idiosyncratic secondary characters whose assorted eccentricities were designed expressly to assail Paw with modernity in all its variations and varieties. Polly eventually faded into the background, but in the early days of the strip, she attracted considerable attention for daring to display her long legs. And in her facial profile - bulging brow, tiny nose, pouting mouth - Sterrett established a convention for depicting a pretty girl's face that was widely adopted by other cartoonists. But little else about Sterrett's way of drawing could be readily imitated.

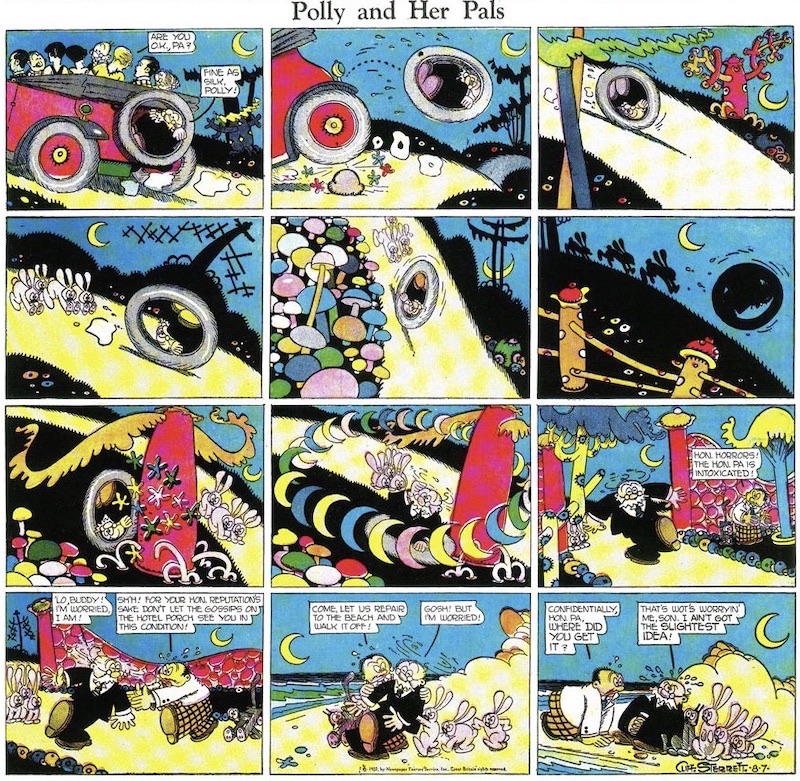

As his style matured in the mid-twenties, Polly became a spectacular symphony of line design in black and white in daily strips and a riot of primary colours on Sundays - rampant reds, succulent yellows, pristine blues. The stylistic earmark was the interplay of patterned line and geometric shape. Checks, strips, black solids, quilt-like patchworks, and surrealistic backgrounds were juxtaposed in panels populated by creatures whose anatomy was wholly abstract, completely geometric in cubism's Futuristic manner: heads were simple spheres; bodies and limbs, cylindrical tubes. This abstraction of the human form permitted widely unrealistic but supremely comic expressiveness in both face and feature, and Sterrett exploited the possibilities with playful exuberance.

Kitty, the family pet, for instance, became a completely geometric cat, assuming a larger significance in the strip's motif: her geometry made her as anthropomorphic as her owner, and she emerged as a Greek chorus, commenting on Paw's predicaments by outright imitation of his actions or in her exaggerated reaction to his moods.

Inspired by the surrealistic impulses of modern art as well as Futurism, Sterrett's Sunday pages in the late twenties in particular were unparalleled in their comic distortions of reality, in their subordination to abstract design of the representational mission of the drawings. The pages were agog in exotic potted plants, fanciful embroidered pillows, abstracted cityscapes, outlandish tubular trees with electric foliage zig-zagging across the sky. Any many of the gags seemed dictated by Sterrett's desire to draw certain subjects in certain ways, often experimental. It's midnight on one Sunday and the panels are mostly black, the action revealed solely in patches of light; on a Sunday at the beach, all the action id depicted under water, and we see only the distorted bottom portions of the characters wading.

By the 1930s, Sterrett's drawings were less inventive: the surrealistic elements disappeared, leaving just the geometric forms of Futurism, and these had become mere conventions. Suffering from arthritis, Street surrendered the art chores on the dailies to an assistant; the last Sunday Polly was published June 15, 1958.