(Impact #1 cover art by Jack Davis)

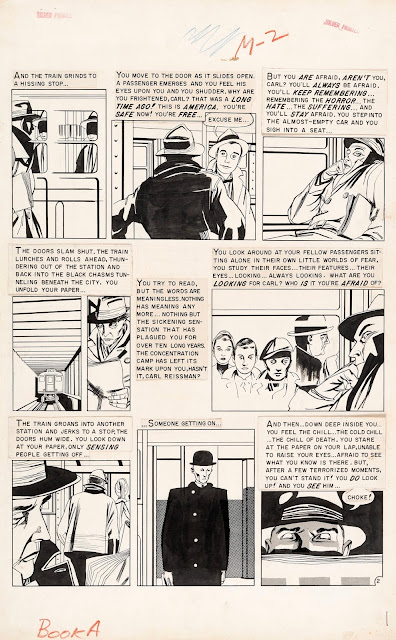

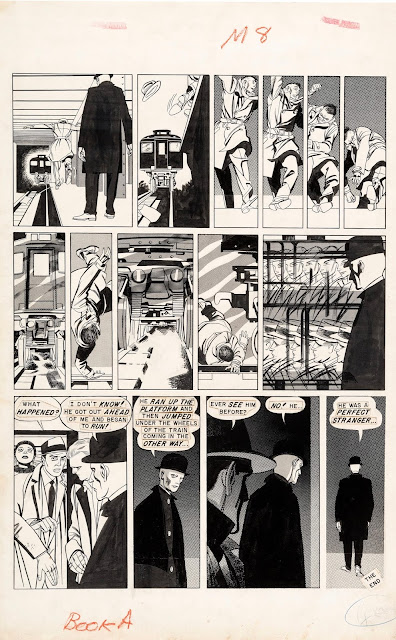

The script, credited to the underrated Al Feldstein, tells the story of a chance meeting between a former concentration camp commandant and a camp survivor on a New York subway. The encounter ends with the former Nazi's death. As a straight piece of drama, Master Race is a solid, capable work of fiction. Feldstein's script is professionally forceful and provocative, while Krigstein's illustrations serve the story's dramatic highlights perfectly: the depictions of both the chase and the commandants crimes are magnificently expressive without veering into melodrama.

However, Master Race is best remembered for Krigstein's exploration of the possibilities of narrative in comics form. Expanding the script from six to eight pages, Krigstein opened up the story's graphic possibilities. His solutions to various storytelling problems are incredibly sophisticated: radical shifts in perspective between the pursuer and the pursued; building mood through panel size and text placement; switching from objective to subjective viewpoints; and showing dramatic highs by slowing down the action across a series of panels. The panels where Krigstein shows the passing of the subway cars through repeating images within the same panel are so astonishing, so adept, and so perfect they serve as arguments in and of themselves that Master Race is a rare artistic achievement by one of comics greatest forward thinkers.

Master Race is also one of the most studied comics of all time, most notably in the seminal piece of comics criticism "An Examination of Master Race" (by John Benson and David Kasakove, working in part from an Art Spiegelman essay and close reading of the story). A perfect marriage of artist, approach, and subject matter, Master Race rewards the constant reconsideration it richly deserves.

I met him only once, in the early seventies. John Benson, the editor of an EC fanzine called Squa Tront, wanted to expand and publish a panel-by-panel analysis of "Master Race" that I had written in 1967 as a college term paper. We went to visit Krigstein at his painting studio, on East Twenty-third Street, so I could read it to him and get his responses. Krigstein at first demurred that those days were long behind him and he didn't remember much about the work. As I began reading, he entered into the analysis avidly, acknowledging a reference to Futurism in one panel, to Mondrian in another, denying a reference to George Grosz in yet another. He basked when I pointed to a visual onomatopoeia that conjured up a subway's rumble. It was as if messages he'd sent off in bottles decades earlier had finally been found.

At the end of the paper, I had compared his approach to that of some important contemporaries whom I also admired, including Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner. When I read that paragraph, Krigstein darkened. "Eisner!" he shouted. "Eisner is the enemy! When you are with me, I am the only artist!" He yanked me further into his studio and pointed at the walls. "Look!" he roared. "You see these paintings?" I saw several large, molten, and lumpy Post-Impressionist landscapes in acidic colors. "These are my panels now!" His voice betrayed all the anguish of a brokenhearted lover.

REVIEW BY DAVE SIM:

All they have to do is give him his own book, as they did with Kurtzman, and comic books could have jumped three or four decades in maturity inside of a year. No go. In fact, just the opposite happens. They start cutting the page count. To me it was an object lesson in the fact that innovation and business interests, while completely compatible are seen by businessmen as completely incompatible... If in later years, long after I'm dead, someone sees something in my work that seems - to them - as innovative as Master Race seemed - and seems - to me... Well, I'm pretty sure they will also see that what I achieved was only possible through self-publishing and, hopefully, I will have saved a handful of future creators from hitting a brick wall at their innovative peak that Feldstein and Gaines forced Krigstein to hit at his own creative high point.

Impact #1, EC Comics, 1955

(Click images to enlarge)

No comments:

Post a Comment