I read about David Bowie in a newspaper before I ever heard his music. I was eleven. The article in a daily newspaper was about Bowie saying he was bisexual, a term I had never previously encountered. The people who wrote the article seemed more shocked that he wore makeup. A man wearing makeup. Had you ever heard of such a thing?

Not long after that, I heard a song on the radio about a spaceman leaving his capsule on a space walk; it was being played in the school's hobby room, where the kids were allowed to go and make balsa wood airplanes. I didn't really get pop music at that age. I loved Gilbert and Sullivan; I loved songs that were stories, and most rock and pop wasn't. "Space Oddity" was a story, even if it left its ending wrapped in ambiguity, and it was science fiction, and I loved and understood science fiction.

And really, it was the science fiction that was the fishhook in my cheek and dragged me in, as much as the music. Perhaps more than the music. I would listen to music that I didn't love, to tease out the ideas, and play it enough that I loved every beat and bar of it. For me, it was the thread that linked The Man Who Sold The World - "The Supermen" and "The Man" himself - with Hunky Dory - which gave me "Changes" and Quicksand" - and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, a sci-fi journey. It started with a heartbeat that told us that we only had five years until the end of the world and took us to a room where a kid my age was listening to a Starman sending in music from outer space. The other side of the record was the story of Ziggy Startdust and his journey from fame to zombie obscurity, and I was certain that Ziggy was an alien, come to bring us music. The Starman had descended into a world that was ending in five years, and he would finish his life wandering dully, insulated from from all feeling, like Thomas Jerome Newton drinking himself into painlessness.

I was twelve when Aladdin Saine came out, and I was bedazzled and confused, and I wanted to know who the strange ones in the dome were and why Aladdin Saine was going to fight in the Third World War, and I held on to the conviction that this was science fiction. I was thirteen when Diamond Dogs hit, and I was so much in love I went to the school library and took out George Orwell's 1984 and build huge sapphire-coloured post apocalyptic sages in my head out of the rest of it.

At fifteen, I bluffed my way into a showing of The Man Who Fell To Earth, acting old enough to be allowed in, and I bunked a day off school to go to Victoria Station for Bowie's arrival there (I didn't see him, but I met people who were different Bowies at different periods, and I saw copies of Station To Station flung over the wall they had put up to stop us from seeing him, and I felt like I was touching magic).

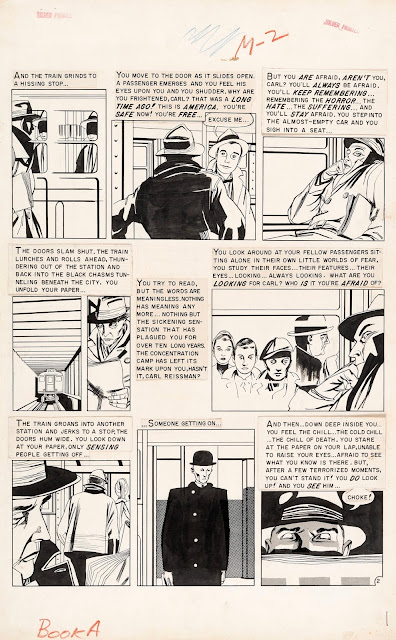

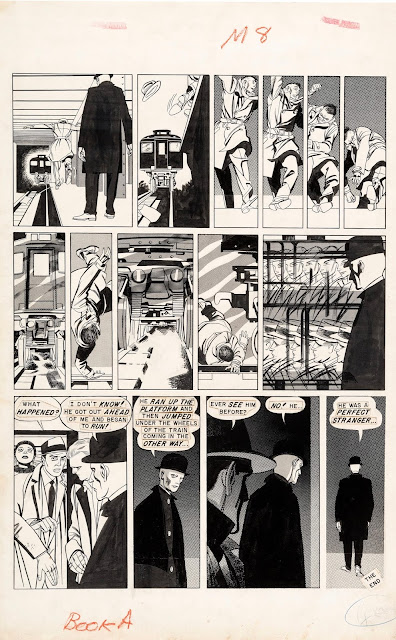

The incarnations of Bowie were, in themselves, science fictional. All I was missing was a Bowie comic, and, missing it, I would draw bad Bowie comics myself.

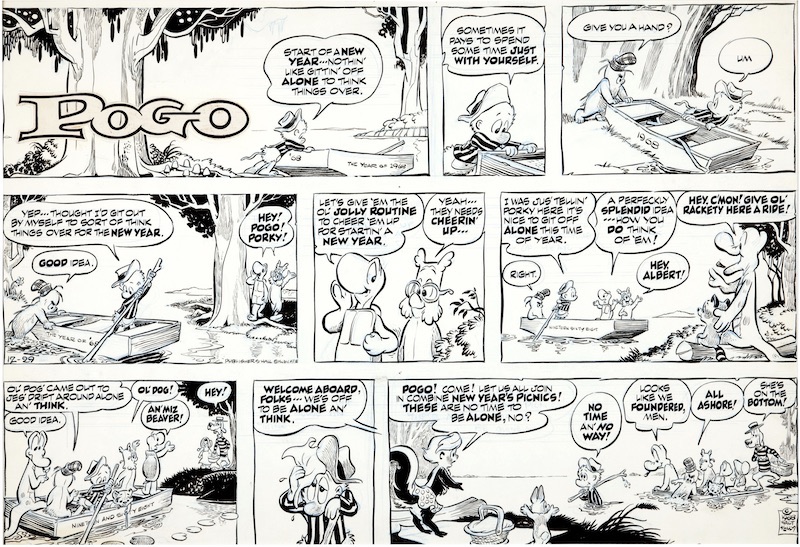

I met Mike Allred around 1989, at (I think) a Forbidden Planet signing. He gave me some of his art, and I loved it. I sent it to Karen Berger, my editor on Sandman, who had him do a tryout page and told him he wasn't quite ready yet. I continued to love his art and was proud that the world rapidly discovered how good he was and that, together, we would bring back the character Prez in the pages of The Sandman: World's End. Later, we would make one of my favourite comics I had any part of: the Metamorpho story in Wednesday Comics, complete with a 1963-style periodic table. There was a cleanness to his lines, a joy in the image and in the construction of each page, aided and abetted by Laura Allred's precise and delightful colouring.

There was a brief moment in the early 1990s when rock-and-roll biography comics were the next big thing. It didn't last very long. None of them were like this. This is pure delight, a book made by fans who were also artists, for fans who are dreamers.

This is a book filled with visual allusions (my favourite is the Hunky Dory "Quicksand" first Spider's gig page). The people in these pages aren't people. They are icons - larger-than-life versions of themselves, filled with resonance. It's Bowie's life as parables and imaginary histories, a beautifully researched re-creation of something that might be better than documentary footage. It's an imaginary reconstruction of the time and lives of an imaginary figure, inspired by the life of the actor, one David Jones, formerly of Bromley and originally of Brixton.

FURTHER READING:

AAA Pop

Insight Editions

Michael Allred: Conversations (UPM, 2015)