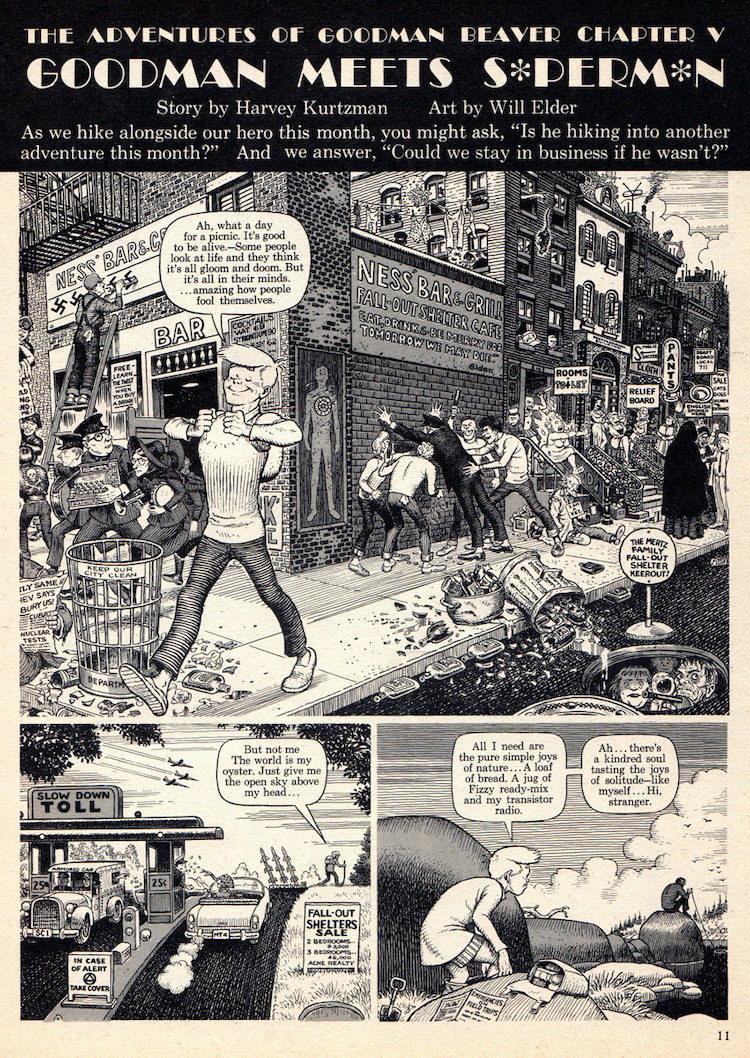

The stories in that volume and the Kurtzman stories I discovered later brandished satire like a monkey-wrench: a wrench to throw amongst pop culture's gears or else employed to wrench all our perceptions just a quarter-twist towards the left, no icon left unturned. King Kong and Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes and Superman were rendered naked and absurd by the device of draping them with realistic failings and then setting them against a gross yet realistic world where Wonder Woman marries her romantic interest and ends up shackled to a stove, hemmed in by hyperactive kids. Where all the slapstick violence Maggie dishes out to Jiggs results in ugly bruises, blood-stained collars and the bleak depressions of a battered spouse.

The first time I met Harvey Kurtzman, it was in peculiar and somewhat inauspicious circumstances, over a hotel breakfast in San Diego. Julie Schwartz, aware of my admiration for Harvey's work, had decided to drag me over to the table that Kurtzman was sharing with Jack Davis and make introductions, which effectively made me feel like an awkward, party-crashing nerd from the very outset. Added to this, Harvey was still apparently nursing some obscure minor grievance of possibly pre-war origins against Schwartz, which he vented by pretending to mistake Julie for Robert Kanigher. Brief and largely bewildered introductions were made, and I returned to my orange juice and eggs.

The next time I met Harvey, it was halfway through what was, for personal reasons, probably the lousiest week of my life to date. As a confirmed stick-at-home, I was in France. As a certified convention-hater, I found myself attending the Grenoble comic convention. Beyond this, I was in the middle of a complex and painful relationship-breakdown and I felt wretched, a bone-marrow misery that went on for months.

It's strange, then that this singularly lousy week should also contain a few of the most golden and idyllic hours that I can ever remember spending. Halfway up a mountain, in blazing sunlight above the snowlike, I sat at a cafe table with Harvey Kurtzman, drinking beer while Harvey, suffering from the debilitating effects of Parkinson's disease and bundled up warm on an already warm day, drank cocoa. We both had our families with us, and Harvey's daughter took my daughter's up for a trip in a light aeroplane while we talked with Harvey and his wife Adele.

I don't remember every word we said. I wish I did. I remember that he said Watchmen was "a damn fine piece o' work," and I know that it's one of those memories that I'll still be clutching at pathetically when I'm old and spent. I remember that he seemed surprised when I told him that Watchmen wouldn't exist if he hadn't skewed my perception of the super-hero genre with works like Superduperman. He looked amazed, almost bashful, unbelievably enough, and he said, "Well, how about that?" We talked, unsurprisingly, about comics. I told him about working for DC, how you know they're going to end up owning your creations going in the door, but how at the time you assume, with the total folly of youth, that it isn't important; that you will always have an inexhaustible supply of good ideas. He nodded. "That's true. What you said about assuming that you'll always have ideas, that's very true." Adele asked if he'd like another cocoa. He said, "No, I'd better not. I might start something." I remember all these things, small and useless as they are.

The last time I saw Harvey Kurtzman was the next morning. He and his family were leaving the hotel, taking an early flight back to the States. I hadn't slept, and had come down to the lobby in search of fresh cigarettes only to find Adele, anxious because their taxi had arrived and Harvey was missing.

I found him on the first floor, unable to get his baggage into the elevator due to the ravages of Parkinson's. I helped him get everything downstairs to the taxi, and he was painfully grateful. Bearing in mind that every good idea I ever had was probably ripped off of Harvey Kurtzman, I told him to forget it. That it was a small thing. A brilliant, vital mind trapped in a body that no longer responded properly, he replied that I was wrong. That it was a goddamn big thing. He got in the cab. They drove away towards the airport.

Harvey Kurtzman, the one I last saw that morning is gone. The Harvey Kurtzman who exists in my mind, in my work, in every line I write, he's not gone at all. He's there forever.

Harvey Kurtzman (1924-1993) was an American cartoonist, writer, editor and pioneer of comics. He is probably best known for creating the trailblazing and revolutionary humor magazine MAD in 1952 before eventually leaving the publication in 1956. However, his influence extends far beyond that legendary 28 issue run, with his work continuing to inspire generations of cartoonists worldwide. Following his work on MAD, Kurtzman would go on to create a variety of seminal works of the medium including Trump, Humbug, Little Annie Fannie, The Jungle Book and Help! During this time, he helped to discover and mentor a number of diverse talents including Terry Gilliam, Gloria Steinem, Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb. Known for his social satire and pop culture parodies, Kurtzman is looked upon as one of the most influential pioneers of comics whose towering and iconic shadow still looms large today.