I’m staring at a split and tattered copy of Will Eisner’s A Contract With God, signed by the author nearly four decades ago. Published as a modest paperback in 1978, the book has since been cracked open, laid flat, studied, and scanned so many times that its once-sturdy binding has surrendered in half a dozen places. It’s more a “stack” than a “book” after all these years; yet I keep reaching for it, despite more recent and structurally sound editions sitting nearby.

More than any other book in my collection, A Contract With God transports me to a very specific time in comics history: the late ’70s, when the art form of comics felt alive with possibilities to me but dead as a doornail to Americans in general - a musty, decaying relic of a bygone era. Eisner’s book connected with me as a sign of what comics could be. It wasn’t a product of its time, nor did it seem to rebel against its time. It existed in its own continuum, patiently waiting for the rest of its kind to quietly arrive - by the thousands as it turned out - on the shelves of North American bookstores.

I turned eighteen in 1978; a high school grad from Massachusetts, starting as an art student at Syracuse University. I’d been obsessed with comics for four years at that point and determined to make them my career. My friend Kurt Busiek had gotten me hooked on superhero comics in middle school, spurring my decision to draw them professionally, but even then I knew there was more to comics than “the guys in tights.”

Thanks to a good library, a great comic store (the Million Year Picnic in Cambridge), and knowledgeable friends and mentors Richard Howell and Carol Kalish, Kurt and I were able to cast a wide net as we learned about the world of comics. We read golden age comic strips, innovative EC Comics from the ’50s, mainstream masters like Jack Kirby, underground comics from the ’60s and early ’70s, the earliest alternative and independent comics, and contemporary European comics through translations in Heavy Metal magazine. Among the most valuable of those discoveries to me were the reprints of Will’s Eisner’s The Spirit.

The Spirit was a proto–comic book published as a newspaper insert in the early '40s, concurrent with the beginnings of the American comic book industry and the first appearances of Superman, Batman, and their ilk. The stories featured a masked - though hardly superhuman - hero, fighting crime in settings both exotic and mundane. The stories were engaging, funny, and even profound at times, but most important, they made use of a dizzying array of inventive, graphically sophisticated, visual storytelling techniques unlike anything else in America at the time.

Even as a kid in high school nearly forty years after its original publication, I could tell how ridiculously far ahead of its time The Spirit had been. Parallel narratives, full-page compositions, noir shadow play, giant logos integrated into physical scenes, long pantomime sequences - the strip was a textbook demonstration of nearly everything comics could do, answering questions about the art form most cartoonists hadn’t even thought to ask yet. And the more I studied those pages, the more I came to understand that Eisner’s approach to comics storytelling had been the foundation upon which multiple generations of cartoonists had constructed their own dreams of adventure in the years and decades that followed.

I wondered - in those days before the Web and fast, easy answers - what Eisner had done with himself after The Spirit wrapped up its run in the early ’50s. It turns out that while Eisner still believed in comics' literary and artistic future, the industry faced setbacks, including McCarthy-era anti-comics campaigns in the '50s that put some of the most innovative titles, companies, and cartoonists out of business. Eisner found safe harbor making comics-style instructional manuals for the Army (innovative in their own way and significant for those of us who make nonfiction comics today), but his early dreams of comics as a literary form had to take a backseat for nearly three decades. When the creative explosion of underground comics arrived, he found renewed inspiration to finally create the kind of work he had imagined comics were capable of from his early years drawing them.

Eisner never lost his faith in comics as a literary and artistic form, but those many years between the end of his Spirit run and the creation of A Contract With God in 1978 had changed his artistic approach: from cinematic to theatrical, from escapist to personal, from restlessly inventive to patiently introspective. He was now a different kind of cartoonist. The Spirit had been an exuberant declaration of comics’ potential. A Contract With God gave the impression of an artist who quietly assumed that potential was common knowledge. At fifty-nine years old, retired from the Army, Eisner had seen the comics industry die and be reborn multiple times, but the art form wouldn’t quit and neither would he. Eisner was playing a long game.

Eisner didn’t invent the term "graphic novel" - it had been floating around for a few years beforehand - but everything clicked when he attached it to A Contract With God. So much of American comics culture was about regurgitating the superhero mainstream or rebelling against it, but here was something different: an earnest, personal, lovingly crafted collection of stories of ordinary people, rooted in the cultural history and personal experiences of its author. Every positive association that the word “novel” possessed seemed tailor-made for the book (even though it was actually an anthology of four interconnected short stories).

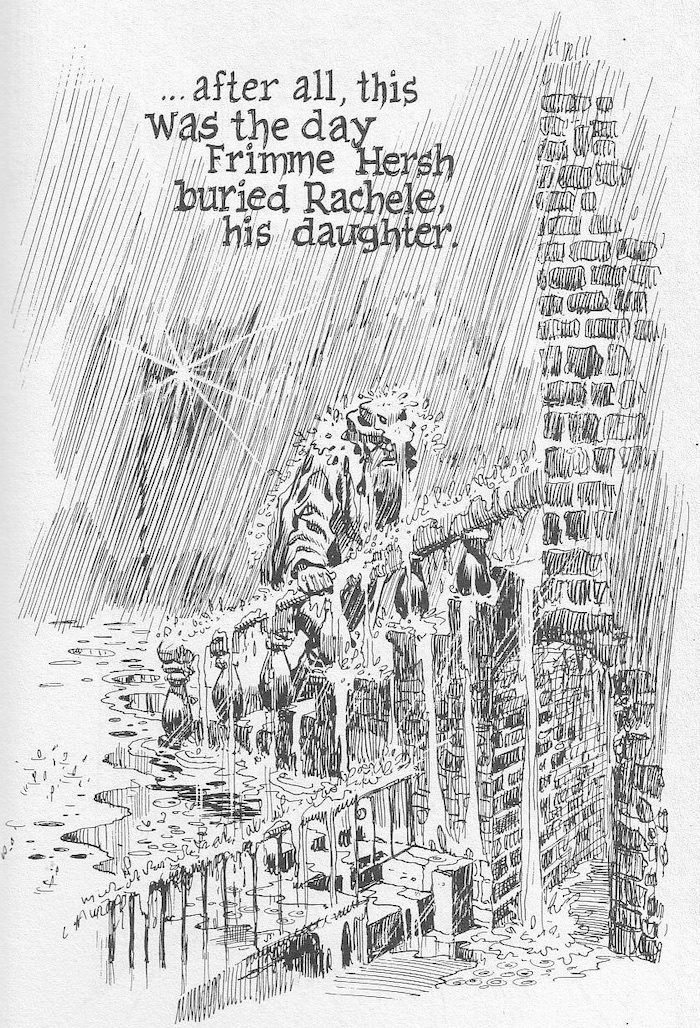

Eisner’s visual storytelling style in A Contract With God bore little resemblance to anything else on the shelf at the time. His line work, always a strength, had matured tremendously. It was rough-hewn but precise, harkening back to Heinrich Kley, and it had some of the flavor of the early twentieth-century woodcut novels of Lynd Ward and Frans Masereel that Eisner admired. The style was cartoony, the body language and facial expressions nearly operatic in their intensity, but there were odd narrative turns and moral ambiguity at play too. The cityscapes and interiors created a strong sense of place, with the authority of a sharp and vivid memory; yet somehow, whatever nostalgia they might’ve evoked, the human drama at the heart of it all felt fresh and new - at least to me, as an eighteen-year-old reader in 1978.

Eisner kept going, kept making new graphic novels for decades as others joined him. Mainstream companies cheapened the term with their own slapped-together reprint collections of popular superhero titles, but a growing roster of artists followed Eisner’s example and created their own original book-length efforts. Within the first few years, there were enough to fill a shelf, then a bookcase, then a row of bookcases, and today, graphic novel sections are a familiar fixture in nearly any major bookstore chain.

Much of that market growth can be attributed to the outsize achievements of artists like Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Marjane Satrapi, and Alison Bechdel, whose books have generated prestigious prizes, enumerable college courses, and even a hit Broadway play. And the manga craze and growth of popular all-ages comics didn’t hurt either. But through it all, Will Eisner’s drumbeat kept time for the American graphic novel movement.

Will Eisner was sixty-five years old when I met him in 1982. I had just graduated Syracuse with a degree in illustration and somehow - miraculously - landed a job in DC Comics’ production department in Rockefeller Center. I was only twenty-one years old and impatient to begin making comics of my own professionally. Eisner welcomed me into his home to look over my work, allowed me to sit in on some of his classes at New York City’s School of Visual Arts, and in the years to come, as my own career took hold, he welcomed my family into his ever-widening circle of friends. Despite being as grand a "grand old man" as anyone could hope for, Will never stood on ceremony. He eagerly participated in debates with artists young enough to be his grandchildren, and harangued his oldest peers to wake up to the possibilities of new trends. When he died at the age of eighty-seven, we all felt, quite sincerely, that the man had died long before his time.

For all his youthful curiosity and enthusiasm, though, his most enduring lesson to me was his patience. In those early years, when I first met Eisner, I couldn’t wait for cartoonists everywhere to wake up to the potential of our art form. Tomorrow! - today! - yesterday! Eisner made many of the same arguments and did what he could to affect positive change, but if it took a year, or a decade, or even a series of decades, well, so be it. Now, thanks to his example, I’m playing that long game too.

Will and I talked about everything under the sun through many encounters over the years, but we never talked about Alice, the daughter that Will and his wife, Ann, lost to leukemia at the age of sixteen. Will’s grief and rage following Alice’s death gave birth to the title story you’re about to read, but it only came through her father’s pen at the time - not through his voice. He and Ann didn’t talk about Alice publicly for many years, and many of us didn’t even know the truth beyond occasional whispered rumors until a new century began and the old man finally opened up.

I was impressed by how Eisner the artist could encounter one professional frustration after another and still keep drawing - still believing in the potential of an art form that might go for decades without proof of its worth. But I’m awestruck now, looking back as a father myself, at Eisner the man, and how Will and Ann together were able to stay the course and embrace life the way they did after walking through Hell. I’ve never met a more optimistic mind in many ways than Will Eisner, but he didn’t come by that optimism easily. It could have melted in the heat, but instead it was forged into something sharper, and no less durable.

I’m writing this in 2016, more than a decade after Will Eisner died. The potential of comics is being demonstrated daily in ways Eisner anticipated when he created A Contract With God nearly forty years ago, but also in ways he could’ve hardly imagined. And of course, inevitably, the book itself will suffer the fate of any first-of-its-kind pioneer. It’s been joined now by so many of its kind that it’s easy to lose it in the crowd. There are now graphic novels with ever more complex formal ambitions, with subtly written dialogue, up-to-date sensibilities, pitch-perfect irony, and politically urgent subject matter. Graphic novels proliferate and improve with every passing year. But they’re still branches on an immense family tree that was once just a sapling - planted in soil he always knew was fertile.

Scott McCloud is the author of Understanding Comics, ZOT! and many other fine comics.