by Howard Cruse

ALISON BECHDEL:

A few days after turning in my text for this introduction to Stuck Rubber Baby - a slight updating of the one I’d written for the 2010 edition - I learned that Howard Cruse had died. I’d known he was sick, but things took a turn, and at 75, he was suddenly gone. I felt hollowed out with a particular kind of grief I hadn’t felt before. Losing a mentor has some similarities to losing a parent. Howard had in many ways made my life as a cartoonist possible, thanks to his trailblazing career. And I was lucky enough to have a warm personal relationship with him over the years. But I didn’t spend much time in Howard’s actual presence. What I’d spent time with was his work. And now there would be no more of it.

In light of this, I’ve revised the introduction once more, to encompass not just Howard’s masterwork, but his legacy. A key part of that legacy is something that may not withstand the test of time as well as the work itself, so I want to mention it first: Howard’s personal kindness. His compassion, generosity, and lack of ego permeate his work, too. But I have run across very few artists or writers who in person are anywhere near as nice as this guy was.

The best of movies, TV, books, music, and more, delivered to your inbox three times a week.

Howard was born a preacher’s kid, which perhaps explains some of his gentle amiability. (His first cartoons were published in the Baptist Student!) He grew up in the South in the 1950s, dreaming of being a syndicated cartoonist and struggling to quash his desire for other boys. The tensions of growing up gay in that time and place are illustrated succinctly in a later cartoon in which an anxious, brush-cut teenager flips through A Pocket Guide to Loathsome Diseases at a newsstand, next to a rack of books from “Devotional Fatuousity Press” that includes Jesus’s Favorite Recipes.

It took Howard a while to come to terms with his sexuality - on the way, he tried going straight, which resulted in an accidental pregnancy. (He and his girlfriend put the baby up for adoption. Later in life, their daughter would track Howard down and they’d enjoy a warm connection.) By the 1970s, the humor comics Howard had grown up emulating were beginning to disappear, and the underground scene was taking off. He began drawing his philosophical and psychedelically infused strip Barefootz, which would eventually include a gay character.

In 1979, the comics publisher Denis Kitchen invited Howard to edit a new comic book of work by gay cartoonists. Howard had to weigh what this might mean for his career - would coming out consign him permanently to the margins? Fortunately for all of us, he accepted the challenge - and then some. Howard was adamant that the contributions of men and women to Gay Comix be 50-50, even though at that time lesbian cartoonists were much fewer and further between than gay ones.

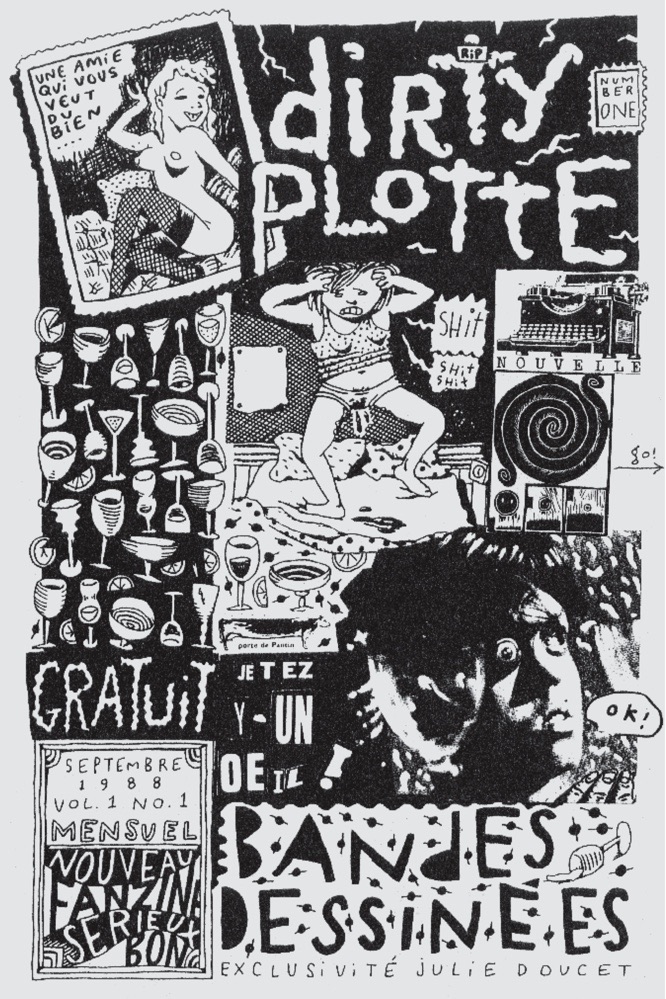

Cover art by Rand Holmes

I happened to stumble onto Gay Comix No. 1 in a gay bookstore in the Village practically the moment I moved to New York City after college. This would prove to be a conjunction as fruitful for me (I like to think) as was Howard’s own happenstance encounter with the Stonewall riots one night a decade earlier when he was tripping on LSD. Here were comics by gay men and lesbians about their regular, everyday lives, including Howard’s moving, hilarious, and magnificently drawn Billy Goes Out. I was inspired by this to start drawing my own cartoons, and I was not the only one. As Justin Hall, editor of No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics, puts it, Howard is “the godfather of queer comics.”

The founding premise of Gay Comix - that gay people are “regular human beings” - was carried over by Howard into his next project. Wendel, the serialized strip he wrote throughout the 1980s for the Advocate, was not just a witty and densely detailed tale of gay life, but a record of the Reagan administration’s virulent homophobia as the nation was grappling with AIDS. Our collective memory is already beginning to forget this recent past, so Wendel is now an important chronicle of the lived experience of those years.

by Howard Cruse

Howard’s next act would be his most ambitious yet: to write a graphic novel based loosely on his own coming of age in the Jim Crow South. It would take on racism and homophobia, with the idea of truth telling at its core. A country that wouldn’t admit, let alone confront, its own racism was telling a lie. The secretive life that many pre-Stonewall LGBT people were forced to live constituted a different kind of lie, but one equally destructive of integrity and connection.

I had the honor of receiving a visit from Howard during the time he was drawing Stuck Rubber Baby. He and his partner, Eddie, were in Vermont for a little vacation, though of course it was a working vacation for Howard, and he’d brought pages along to ink. After we’d visited a bit, he went out to the car to get some of them to show me.

This was over 25 years ago, but my memory of the scene is very clear. As Howard came back inside with a large, flat box, time seemed to slow down. I won’t claim that I could see his aura, or that the artwork vibrated in my hands as I examined it. But there was an energy emanating from these sheets of Bristol board that could not be accounted for merely by the exquisitely designed, lettered, and inked details that met my eyes.

I expect that I was experiencing a reverberation of the intense effort - mental, emotional, and physical - that Howard had invested, and would continue to invest for some time, in this drawn world.

The formal virtuosity of Stuck Rubber Baby, its ambitious historic sweep, its rich characters, its unflinching look at sex, race, violence, hate, and love, make it an immersive, truly novelistic reading experience in a way that’s still uncommon for graphic narrative to achieve.

I identify uncomfortably with the young Toland Polk, the archetypal nice person. A white Southerner who grew up steeped in the casual as well as institutional racism of Jim Crow, he wouldn’t intentionally hurt anyone - but then again, he doesn’t intentionally do much of anything at all. He’s drifting along, equally disengaged from himself and from the world. But inevitably, he’s caught up in the forces of change sweeping past him, and as his engagement builds, so does ours.

This is not a revisionist fantasy in which the white hero flings himself wholeheartedly into the civil rights movement. Toland’s transformation is tentative, conflicted, alternately self-flagellating and self-serving - it’s a scathingly honest portrayal.

He’s surrounded by more active participants in the struggle, as finely drawn as Toland is. The patient, simmering Reverend Pepper. His wife, Anna Dellyne, the ex–jazz singer who now only sings hymns and freedom songs. Their gay son, Les, who turns from party boy to preacher’s kid “at the flick of a switch.” The flamboyant, wounded Sammy. And the brave but exacting Ginger Raines, the woman Toland convinces himself he’s in love with. Ginger is a curious pivot for Toland, leading him toward the truth of civil rights activism, but also affording him the false front of heterosexuality.

What complicates and expands this story like a fifth dimension is Toland’s growing acceptance of his desire for other men. I suspect this also complicated the reception of Stuck Rubber Baby when it was first published in 1995. The parallels Cruse establishes between racism and homophobia were perhaps just a little too ahead of their time to allow the broad mainstream embrace the book should have received.

The “fag bar,” the Rhombus, is Toland’s first encounter with a roomful of gay men and lesbians, but it’s also the first racially integrated space he’s been in. The black drag queen Esmereldus does Doris Day, singing, “When I was just a little girl, I asked my mother, ‘What will I be?’ ” In simple scenes like this, without ever resorting to rhetoric, Cruse deftly deconstructs race and gender more effectively than a shelf full of theory. In a way, Stuck Rubber Baby is an equal and opposite reaction to the vicious bombing at the center of its narrative. Cruse lays bare the mechanics of oppression like an explosives expert taking apart and defusing a ticking lethal device.

Clayfield is a thinly disguised version of racially riven Birmingham in the early 1960s. The pivotal episodes of violence and protest in the book are based on real events. And although the characters and story are made up, Cruse doesn’t shy away from the fact that he has drawn readily from his personal experience, notably his “encounter with unintended fatherhood.” This blend of documentary and fiction yields the best of both worlds - the suspense of a carefully crafted plot and the vivid immediacy of an eyewitness account.

Although the story is told by a middle-aged Toland looking back on his life, and is thus, strictly speaking, a first-person narrative, his take on the events is panoramic and omniscient. It was risky for a white author to write about African American characters, particularly ones who are actively engaged in the civil rights movement, but Howard nimbly clears the bar. He’s done his homework, yes, but like any good writer he pushes himself to explore his various characters’ subjectivities as far as it’s possible to go.

The image of Reverend Pepper’s wife, Anna Dellyne, standing at the edge of the crowd at the jazz club Alleysax is one of my favorite moments in the book. She’s aloof, regal, and wistful, half in the light, half in dense black shadow, a distillation of all the opposing tensions that push and pull this book along.

This brings me at last to the drawing. I know it took Howard years to draw this book, but even so, I don’t see how one human being could possibly lay down this much ink in that span of time, even if they never stopped to eat or sleep. Many of the pages are so finely crosshatched that they appear to have a nap - as if they’d feel like velvet if you ran your hand over them.

One stunning thing this technique affords is a very rich palette of skin tones. White and Black characters alike are shaded with loving nuance. Indeed, everything in the book is drawn with manifest love and a profound generosity. Howard re-creates the visual details of life in the South during “Kennedytime” with a staggering archival fidelity. In less skilled hands, this could be obtrusive. But the painstakingly rendered parking meters, textile patterns, vintage appliances, and record sleeves are woven into a meticulous backdrop that allows us to believe in and surrender to the story completely.

I should point out that this feat was accomplished long before there was such a thing as Google Image Search. Howard gathered references not with a few mouse clicks, but by digging around in library picture files, hitting the street with a camera and sketchbook, and by engaging in God knows what other time-consuming analog practices.

It’s always tempting to cheat when drawing, to gloss things over. Like a crowd scene, for example. But look at the people gathered outside the funeral at the opening of Chapter 14. The back of each infinitesimal head is never a mere oval, but always a particular person’s head. Howard’s benevolent Rapidograph achieves transcendence here.

Despite the sometimes microscopic level of detail, this book is always eloquently legible. Howard is fluent with so many comics conventions that these too could threaten to intrude on the story. But his innovative page layouts and panel shapes, the bleeds and fades, the fragmented breakdown of crucial scenes - all these things combine to transmit a multilayered story with seamless coherence.

Stuck Rubber Baby is a story, but it’s also a history - or perhaps more accurately a story about how history happens, one person at a time. What does it take to transcend our isolation and our particular internalized oppressions to touch - and change - the outside world? As Toland Polk begins to engage truthfully with his inner self, his outer self is able to connect with others more authentically and powerfully. Actually, it’s just as accurate to put this the other way around, because those two actions are inextricable from one another.

Toland lives in a place and time where not just Black people but “white n—–s” are routinely terrorized, and where being a “n—–r loving queer” has dire consequences. In a 2009 version of this introduction, I waxed eloquent about how dramatically things had changed - we had an African American president, and support was rapidly building for marriage equality, things I’d never imagined seeing in my lifetime.

In 2019, things have changed dramatically again. White supremacists, neo-Nazis, and anti-Semites have scuttled out from under their rocks and into the public square. The Trump administration is trying its hardest to roll back LGBTQ rights under the claim of “religious freedom.” Immigrants, Muslims, and women are under attack. The arc of the moral universe apparently bends like a corkscrew.

I’ve thought a lot over the years about how the progressive gay culture of Weimar Berlin was wiped out by the Nazis. Could the remarkable advances made by the civil rights and LGBTQ movements be likewise reversible? For a long time I assured myself that no, they couldn’t. The roots of social justice have gone too deep.

1. The Magic School Bus Made the World Safe for Weird Teachers

2. Charlie Kaufman’s Debut Novel Reveals His Genius Has Its Limits

3. What a History of Smells Can Teach Us About Medicine, Misogyny, and Farts of the Past

4. “If All Black Books Were About Racism, Where Would We Go to Escape It?”

Lately, on bad days, I feel less certain of this. But on good days I remind myself of the astonishing achievements of movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. The everyday activism of principled people is an ongoing redemptive force in this country.

In an interview in the mid-1990s, after the first edition of Stuck Rubber Baby came out, Howard said, “This is a book people can live with and revisit and find new subtleties in, find issues that are contemporary even though the story happened 30 years ago. It’s about issues I care a lot about: Is this country going to be a generous country or a mean-spirited country? This is very much on my mind these days.” Now, almost another three decades out, that question could not be more stark or more consequential.

Howard Cruse’s visceral account of America’s recent past contributes with grace and force to the vision of a just world. And it makes an equally vital contribution to the power of graphic narrative to reflect life back to us - in this case the conflict and exhilaration of social change - in all its glorious chaos.

The 25th anniversary edition of Stuck Rubber Baby was released in 2020 by First Second Books.

Alison Bechdel is the author of two internationally acclaimed graphic memoirs, the Eisner Award winning Fun Home and Are You My Mother?. For twenty-five years, she wrote and drew the comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, a visual chronicle of modern life - queer and otherwise.