For one of the most prolific and highly-praised cartoonists who ever lived, George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat (1913-1944), didn’t like talking about himself. Recoiling from photographers and brushing off personal questions with elliptical answers and even occasional fabrications, George or “Garge” or “The Greek” always preferred the focus to be on the multivalent, multifarious, and multicultural characters who populated the inner world he made every day with the scratchings of his pen. A direct throughline of thought-to-gesture in black ink on white paper, George Herriman’s drawings come alive before the reader’s eye with a vital, persuasive complexity previously unknown in the history of art. Krazy Kat lived on the page - but he - or she - had a secret. And so did George Herriman.

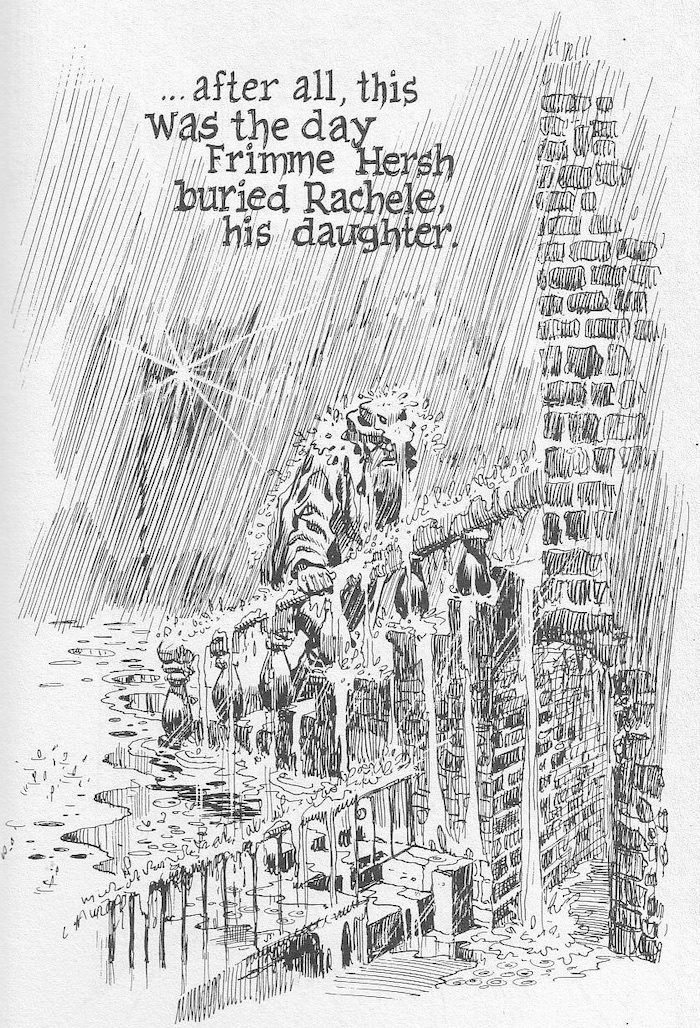

Krazy Kat has been described as a parable of love, a metaphor for democracy, a “surrealistic” poem, unfolding over years and years. It is all of these, but so much more: it is a portrait of America, a self-portrait of Herriman, and, I believe, the first attempt to paint the full range of human consciousness in the language of the comic strip. Like the America it portrays, Herriman’s identity has been poised for a revision for many decades now. Michael Tisserand’s new biography Krazy does just that, clearing the shifting sands and shadows of Herriman’s ancestry, the discovery in the early 1970s of a birth certificate which described Herriman as “colored” sending up a flag among comics researchers and aficionados. Tisserand confirms what for years was hiding in plain sight in the tangled brush of Coconino County, Arizona, where Krazy Kat is supposedly set: Herriman, of mixed African-American ancestry, spent his entire adult life passing as white. He had been born in the African-American neighborhood of racially mixed, culturally polyglot 1880s New Orleans, but within a decade Herriman’s parents moved George and his three siblings to the small but growing town of Los Angeles to escape the increasing bigotry and racial animosity of postbellum Louisiana. The Herrimans melted into California life, and it was there that George, with brief professional spates in New York, would remain for the rest of his life.

But imagine knowing something about yourself that’s considered so damning, so dire, so disgusting, that you must, at all cost, never tell anyone. Imagine leaving behind a life to which you cannot claim allegiance or affection. Imagine suddenly gaining advantages and opportunity while you see others like you, who have not followed in the footsteps of your deception, suffering. Herriman, once he was considered white, didn’t even have a way of voicing this identity. Until he started drawing Krazy Kat.

I may be in the minority here, but I really think that most if not all readers of Krazy Kat during Herriman’s lifetime would have had a hard time thinking of Krazy as anything but African-American. Krazy’s patois, social status, stereotypical “happy-go-lucky despite it all” disposition all funnel into a rather pointed African-American identity. And Herriman, confoundingly, was not above using racial and even racist imagery himself, his early work especially filled with eye-popping stereotypes and blackface caricatures. At the turn of the century, when Herriman was just starting his career, the nineteenth-century cultural phenomenon of blackface minstrelsy, while admittedly in the early process of passing into nostalgia, was still prevalent. Large orchestral shows of dozens of performers like Haverly’s and Christy’s Minstrels, grotesquely metastasized from the already ghastly four-person troupes, filled vaudeville halls and theaters; blackface performances, in a cruel twist of cultural fairness, were the first places for African-American performers to find a foothold. (W. C. Fields called Bert Williams, probably still the best known African-American entertainer from this era, “the saddest man I ever knew.”)

At the same time, a reader alive in the early part of the twentieth century probably didn’t really have to think about these associations any more specifically than we think the “Minions” sound vaguely Latino, or why Felix the Cat or Mickey and his minstrel mouse gloves were so funny. Of course Krazy Kat was black. A funny black cat. Just the right amount of slippage and shift in Krazy’s animus, helped along by a tradition of children’s animal stories, was all that was necessary for him/her to be two things - and nothing - all at once.

Nevertheless, one detail in Herriman’s strip that would have absolutely cemented this identity in the minds of contemporary readers has since passed into obscurity: Krazy Kat’s banjo. Through received clichés and shifts of poverty and culture in America, the banjo has come to be thought of as an instrument of poor whites, but at the turn of the century, it was as emblematic as a watermelon as part of the African-American stereotype. In fact, the banjo has a solemn origin: descended from the West African akonting, xalam, and ngoni instruments, played as an accompaniment to storytelling by Wolof griots in Senegal or the Jola in Gambia, early instruments like what became the American banjo were recreated by American slaves from whatever plantation materials were at hand - gourds, turtle shells, coconuts, animal skins - to try to hold on to a memory of life and culture torn from their grasp.

To the modern reader, the banjo in Krazy Kat might seem a lighthearted accessory, but when Krazy picks it up to sing “There is a Heppy Land Fur, Fur Away”, the meaning, to thoughtful readers of the 1920s to the 1940s, would have been clear. Even more astonishingly, Krazy never plays a “proper” banjo, but plays the gourd or coconut banjo, the origins of which by the time of the strip’s appearance would indeed have been obscure. Herriman knew what he was doing, and it’s not insignificant that the very last strip he left unfinished on his drawing table showed Krazy playing a gourd banjo. The earliest representation known of such an instrument appears in the watercolor The Old Plantation, painted by South Carolina slaveholder John Rose in the late eighteenth century.

What do these racial and cultural connections mean for how we see Herriman’s work? From their dimming over the years compared with Krazy Kat’s increasing artistic incandescence, they are clearly not necessary to an appreciation of the strip. But put yourself in Herriman’s shoes, and then reread Krazy Kat with this knowledge rewoven into the tapestry of his work. Think of pink Ignatz, the mouse who is Krazy’s constant tormentor. Think of the brick. Think of what W.E.B. DuBois called the “dual consciousness” of African-Americans, think of the brick hitting Krazy, over and over and over again. (Tisserand shrewdly notes that a July 30, 1866, New Orleans race riot, which Herriman’s father may have witnessed, started when a white boy threatened to throw a brick at African-American soldiers parading through the town.) Think of what recasting that gesture of hate as one of love actually means to its recipient. Think of the lynchings of the 1910s, the race riots of the 1960s, the American police shootings of 2016, the iPhone videos that continually show the treatment of African-Americans as property. Think of Barack Obama, half Scotch-Irish, half African.

George Herriman saw the history of America and its future and wrote it in ink as a dream on paper, and it is a dream that is still coming true. In December, disparate Native-American tribes and activists who had gathered in North Dakota for months staved off an oil pipeline that would have cut through ancestral Sioux burial lands; Herriman began visiting the Diné or Navajo nation and befriending its citizens before some western states were even twenty-five years old. Navajo rug patterns and the folklore of Monument Valley came to define the very cosmos of Krazy Kat. (A wonderful detail in Tisserand’s book recalls Herriman, who had Hollywood friends, setting up a private screening of older western movies with actual Navajo supporting actors for a Navajo audience, solely because the actors had said insulting things in their native language that only the Native audience could understand.)

And our most recent election involved debates about the equality of transgender teens, of those trapped inside a body by which they feel betrayed. Krazy Kat’s self-defining gender-switching - “I don’t know if I should take a husband or a wife,” Krazy once remarks - couldn’t be more timely, more oracular. Nor, sadly, could Ignatz’s seemingly implacable hatred. Even sadder, in that same American election, Ignatz won.

Everyone “passes” in some way or another; everyone has something they’d rather not discuss, something of their history they’re trying to downplay or hide, some story that doesn’t jibe with the vision and identity they’d prefer to have. This is the essence of fiction. Every one of us nightly, daily, hourly—every minute—reviews, sorts, discards, rewrites details that allow us to somehow get on with our lives, unrecorded acts of revision tantamount to what a writer commits professionally on a page. Do it well, and you’re mentally healthy. Do it badly, and you’re crazy. Fundamentally, we understand others only as refractions through the optic of ourselves, and fiction not only offers an alternative construct, but in its finest form allows the reader to inhabit, and most importantly, to empathize with another consciousness. (Or in Herriman’s case, with a cartoon cat.) So is kaleidoscopic Krazy really the crazy one, whom Ignatz can only understand through the reducing lens of his narrow, white mind?

Lately, I’ve been wondering if Herriman knew that one day his secret-in-plain-sight would be uncovered, that America would change, adapt and grow up enough as a people to understand Krazy Kat in all of its psychological and poetic depth. I’m not sure if we’ve yet reached that point, but what myself and other cartoonists already knew - that the strip was already the greatest ever drawn - is now magnified, multiplied and maximized. Krazy Kat is not just one of the greatest comic strips, it’s one of the strangest, most inventive, emotional, and personal works of art of the twentieth century. In their admiration for Herriman, Philip Guston, Willem de Kooning, and Jack Kerouac sensed something in his line and voice that was endemically American, deeply felt. Herriman should now take his rightful place as one of the most original African-American voices of the early twentieth century, contemporary with, if not predating, Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston as one of the first writers to understand the racial animus of America and to try to fix the essence of black consciousness on paper. That Herriman made it come alive, sing, dance and suffer in an art form barely fifty years old is all the more astonishing. For decades, we’ve all been reading and laughing and, most of all, feeling for Krazy Kat, who passed right under our eyes as a living drawing on a page. But what we were really feeling came straight from the heart. It was the very soul of George Herriman himself.

Adapted from an essay that appeared in the catalog of an exhibition on George Herriman at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain, in 2017.