The following essay is taken from "The Peanuts Papers: Writers & Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, & the Meaning of Life", published in 2019 by the Library of America.

As a kid, I spent a lot of time alone. Because my mother was single and worked all day long, my grandparents’ house became a sort of second home, where, if I wasn’t being monitored directly, I occupied myself drawing or reading while my grandmother and grandfather tended to their yard and housework. My grandfather had been a managing editor of the Omaha World-Herald, where he assumed the makeup of the daily and Sunday comics pages. For him, this task was a vestigial pleasure, because, as a boy, he’d wanted to be a cartoonist, though providence and necessity (he had been booted from college for stealing university stationery and sending a forged letter to all the fraternities mandating that they appear Sunday morning for V.D. testing) had willed otherwise.

As a perk of his role as the comics decider, he’d received collections of the various comic strips that the World-Herald published, and kept them on a shelf in his basement office, which I was free to peruse in my housebound wanderings, while he and my grandmother raked, mowed, and sprayed DDT on their lawn outside. My grandfather had been among the country’s earlier managing editors to add a strange, iconographic, and purposefully designed “space-saving” strip to the World-Herald’s pages, named Peanuts. (My grandmother told me once how she had sat at the kitchen table with him reading the syndicate pitch samples and “howling with laughter.”) I regularly lost myself in these early Peanuts paperback collections. Charlie Brown, Linus, and Snoopy became my friends. At one point, after reading an especially upsetting Valentine’s Day strip, where, as usual, Charlie Brown received no cards, I crafted an awkward valentine and demanded that my mother mail it directly to the newspaper, where I knew she had an “in” and where, somehow, I hoped it might find its way into Charlie Brown’s tiny, stubby-fingered hands.

What kind of artist, through his simple newsprint drawings, could break the heart of a child like that?

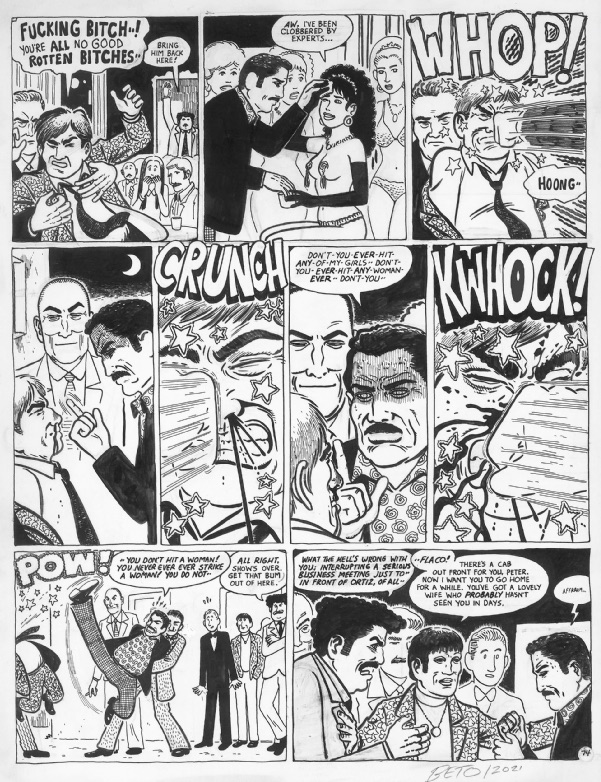

Even the least critical reader can sense falseness and fakery on the part of an unskilled - or, worse, dishonest - cartoonist. And, because the comic strip is a valueless throwaway, the cartoonist must win the reader’s trust without benefit of critical backing, museum walls, and monied collectors. The best comic strips present the cartoonist laid bare on the page; they are a condensed sum-uppance of the artist’s notions of, ideally, what makes life funny, but also of what makes it worth living. This artistic effort has to occur not over a career punctuated by a handful of masterpieces but every single day. The skeptical reader arrives cold to a little slice of comic-strip newsprint and gives the cartoonist four, maybe five, seconds: “O.K., make me laugh.” It’s no wonder that Charles Schulz, the creator of Peanuts, woke up feeling funereal, or like he had a term paper due every morning. Or, as he also said, “In a comic strip, yesterday doesn’t mean anything. The only thing that matters is today and tomorrow.”

It’s not the skill of the drawing, or the lines, or the lettering, or the funny words that make a strip work. Timing is the life force of comics. Without a sensitivity to the rhythms and the music - a.k.a. the reality - of life, a comic strip will arrive D.O.A., nothing more than a bunch of dumb pictures. When the comic-strip reader moves through those four panels containing those little repeating hieroglyphs, the characters must come alive on the page with as much ferocity and resonance as the people in one’s own life and memory. The reader doesn’t just look at Charlie Brown, Linus, Lucy, and Snoopy but reads them as musical notes in a silently heard composition of hilarity, cruelty, and occasional melancholy.

In 1950, the comics page was a more or less settled territory into which very few new features could be shoehorned, and, from the get-go, Peanuts was marketed as a space-saver. The strip was created out of four equally sized panels, which allowed it to run horizontally, vertically, or stacked two by two. The simple, almost typographical reduction of the Peanuts characters - the inflated heads and the shrunken bodies - not only saved editorial-column inches but created room for the words in the strip to be legible. This requirement, nearly alchemically, also enabled the transplanting of the children of Peanuts out of a seen, external world of people and places and into a minimalist, abstract, remembered, and internal world. Who would’ve thought that such a hard-nosed commercial decision would catalyze one of the greatest works of popular art of the twentieth century?

Indeed, the earliest Peanuts strips almost seem to take smallness as its peeved raison d’être, a sort of humiliation that the characters must suffer in a space unaccommodating to their bigger ideas, urges, and emotions. The Peanuts characters evolved rapidly right before readers’ eyes during the first two years of the nineteen-fifties. Schulz instinctively allowed just the tiniest bit of realism back into their proportions and postures, and somehow, I think, ineffably shaped them within the idiosyncrasies of his own handwriting. By 1954, Schulz was so masterfully intuiting and internalizing his characters that they seemed to burn the page, modulating between whispers and cataclysmic eruptions so violent that the panels could barely contain their fury. The blank, everyman Charlie Brown of the earliest strips gave way to a self-doubting loser; Lucy developed into a tormentor, while her younger brother, Linus, eventually became the strip’s philosopher.

Whereas the daily strip enabled the characters’ personalities to mature, the Sunday iteration - double the size and number of panels, and in color - allowed for an expansion of the strip’s time and space. Here Schulz drew what, by contrast, were redolently realistic suburban settings. This longer form also allowed him to develop his “music,” orchestrating more complex, extended moments than the shorter daily strips permitted. A choice example of a finely tuned Peanuts Sunday strip might be the March 20, 1955, episode where Charlie Brown and Schroeder are playing marbles and Lucy invades their game, getting angrier and angrier at her missed shots (“rats... Rats! rats!”) and then improbably and violently (“What a stupid game!”) stomping all of their marbles flat (stomp! stomp! stomp! stomp! stomp!). The penultimate panel shows her angrily stalking away, a scribbled skein of lines in a balloon above her head - a skein that the reader “hears” as the endnote of the zigzaggy musical composition that precedes it.

By contrast, just nine months earlier, in May, 1954, Schulz had produced a multi-part Sunday sequence that is one of the weirdest hiccups in the strip’s development: Lucy, with Charlie Brown’s encouragement, enters an adult golf tournament. Now, it’s odd enough that these kid characters would even play golf, let alone play in a tournament, but the fact that Schulz would place Charlie Brown and Lucy next to adults - yes, actual adults appear in the strip - feels very, very wrong. The four-week sequence is full of clunkers and disharmonies, producing a queer sense of dislocation and falseness. It’s almost like the strip has the flu. Indeed, even Schulz seems to be aware of the problem - one panel shows Charlie Brown and Lucy through a forest of adult legs, he admonishing her to “just try to forget about all these people... just forget about ’em.” While the experiment proves Schulz’s willingness to test his strip’s limits, it cemented the primary rule of the Peanuts cosmos: adults might be talked about (sports legends, Presidents, Charlie Brown’s father), or even soliloquized (Linus’s infatuation with Miss Othmar), but they must always, quite literally, be out of the picture.

Peanuts increasingly became a strip where the children acted like adults (unlike the very earliest newspaper comics, in which adults acted like children). For a strip, and a nation, riding on postwar economic euphoria, such psychological inversion seems all too appropriate for the baby-boomer readers of its heyday. In the same way that architecture seems both to contain and to affect our memories, something about the synthetic psychological landscape of Peanuts seems to capture the peculiar timelessness by which we imagine and embody our sense of self. To loosely quote Vladimir Nabokov: we all have children buried alive inside us somewhere. “You have to put yourself, all of your thoughts, all of your observations and everything you know into the strip,” Schulz said in 1984. Peanuts could even be tartly described, as Art Spiegelman once did to me, in a phone call, as “Schulz breaking himself into child-sized pieces and letting them all go at each other for half a century.”

Caught up in remembrances of age-old wrongs and slights, Schulz seemed to have well-worn ruts in a road that led backward, the gates of injustice opening on his drawing table with every new strip. Rejections, dismissals, and disappointments flooded into the story lines of Peanuts. So accessible and immediate were these memories that, after the end of his first marriage, he apparently thought it O.K. to pay a visit to his old girlfriend Donna Johnson Wold, a.k.a. the Little Red-Haired Girl, who had rejected him at least twenty years before and was by all accounts perfectly happy being married to someone else. Toward the end of his life, Schulz regularly noted in his school yearbook (from which his drawings had been rejected, incidentally) when his classmates died, one by one. I’ll corroborate: in my own life as a cartoonist, I’ve made similarly ill-advised personal decisions, and sometimes a vicious word spoken by a mean kid to me forty years before will surface while I’m working, and I’ll say something back to him at the drawing table, out loud. There’s definitely something very weird about this profession, and my simply typing “the Little Red-Haired Girl” and not having to explain it demonstrates Schulz’s genius at harnessing it. We all have our own little red-haired girl.

Cartoonists, like dog owners, tend to look like their work, but Schulz somehow skirted that rule, the parenthetical, closely spaced eyes in the middle of Charlie Brown’s fat bald head resembling nothing about Schulz the man, who had widely spaced eyes, a strong, long nose, and an enviable thatch of hair to the very end. But that’s part of Schulz’s talent: Charlie Brown looks less like Schulz than, one must suppose, he feels like him. From the Yellow Kid to Barnaby to Henry to Tintin to Charlie Brown, there’s a long history of large, bald, white male faces through which the reader may “see” these characters’ various comic-strip worlds. This is no accident; the less specificity a character has, the more he (or maybe she—where are our shes?) becomes the strip’s protagonist, an everyman. Culturally, and however unfairly, the pink disc of Charlie Brown’s big baby face is about as blank and everyman as one can get.

For white American males, at least. But Schulz did try: in answer to certain readers feeling “left out” of the strip, the introduction of Franklin, in 1968, came with a rightful dose of dread on Schulz’s part about seeming condescending to African-Americans. He needn’t have worried, though, because Franklin felt real - or at least felt respected - as a kind kid on the beach with whom Charlie Brown plays in the sand. (“Whites Only” pools were not uncommon in 1968.) Though Schulz may have lived a quiet, remote life in his California studio, he was woke enough to realize that all one had to do was care enough about a character for he or she to “work,” even if the shell of the character wasn’t his own. Despite the over-all racial imbalance of the Peanuts cast, this caring is really the secret, mysterious power of Schulz’s entire strip. Charlie Brown, Lucy, Linus, Snoopy, Schroeder, Franklin, and everyone else came alive on that page because of Charles Schulz’s ability to make you care about and feel for - and, in Charlie Brown’s case, at least, feel through - nearly every one of them.

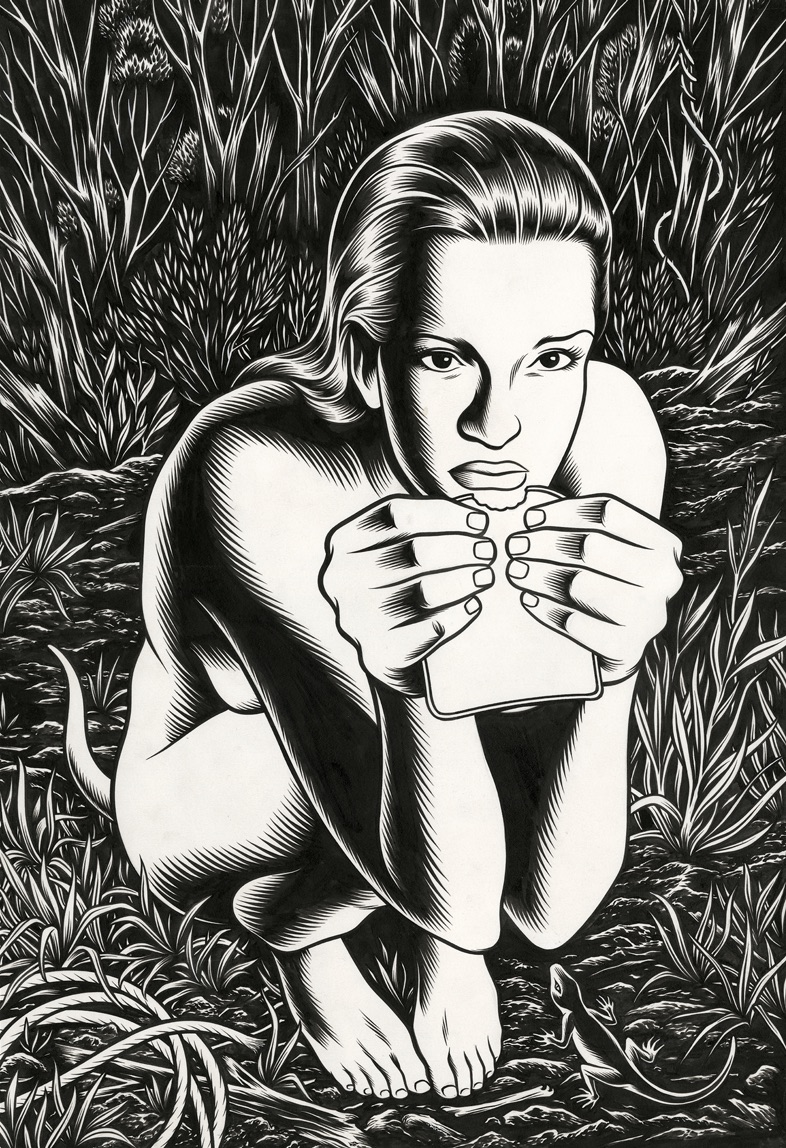

There is a translucency, if not a transparency, to Schulz’s drawing style that allows for such sympathy. It’s not diverting or virtuosic - it’s direct and humble. (He described it as “quiet.”) The simple act of looking from one drawing to the next animates the rhythm of the characters’ movements, echoing, somehow, our own distillation of experience. Due to an essential tremor in Schulz’s drawing hand, as the result of a quadruple-bypass surgery in 1981, this distillation felt shakier in later years; he sometimes even steadied his drawing arm with the other, to reduce the tremors to a minimum. But this difficulty did not change the strip’s essence, or Schulz’s devotion to drawing it: “I am still searching for that wonderful pen line that comes down - when you are drawing Linus standing there, and you start with the pen up near the back of his neck and you bring it down and bring it out, and the pen point fans out a little bit, and you come down here and draw the lines this way for the marks on his sweater, and all of that... This is what it’s all about - to get feelings of depth and roundness, and the pen line is the best pen line you can make. That’s what it’s all about.”

Schulz’s mind, and then hand, transmuted the Peanuts characters onto the paper and then into the eyes and minds of millions of readers, and he knew those readers trusted him to “make the best he could make.” He never gave up on them. Besides, no one else could have done it; despite the deceptive simplicity of a Peanuts drawing, faking one - let alone four of them in a row - is impossible. If there is one accomplishment in the art of cartooning for which Schulz should be credited, it’s that he made comics into a broader visual language of emotion and, more importantly, empathy. For this, all cartoonists - especially those of us who have attempted “graphic novels” - owe Schulz, well, everything.

© Chris Ware