ART SPIEGELMAN:

(from The New Yorker, 22 July 2002)

The current "Spider-Man" movie will sell more Spider-Man toothbrushes, action figures, and frosted Spidey-berry-filled Pop-Tarts in its wake than actual Spider-man comic books: comics are simply not the popular form of popular culture that they were in their mid-twentieth-century heyday, though what the bastard form has lost in popularity it has been gaining in legitimacy. Barely an eyebrow now raises when cartoonists receive serious academic and critical attention, museum exhibitions, MacArthur grants, and Guggenheim fellowships.

Anyone interested in crossing the ever-narrowing divide between High and Low culture ought to contemplate the work and troubled career of Bernard Krigstein (1919-90), a postwar comic-book illustrator who had the privilege and the misfortune of being an Artist with a capital "A" working in an Art Form that considered itself only a Business. Krigstein was never associated with a specific character (the most sure ticket to comics success), and he never wrote his own stories (a handicap in a narrative medium). He wasn't beloved by publishers, editors, or readers. What reputation he has rests on a handful of short stories he illustrated in 1954 and 1955 for EC comics (the folks who brought you Tales from the Crypt and Mad), but one of those stories, Master Race, was an accomplishment of the highest order - a masterpiece.

All eight pages of Master Race are exquisitely reproduced in Greg Sadowski's new coffee-table biography, "B. Krigstein" (Fantagraphics; $49.95), as are a few other key stories and some sample pages, but the entire project is as quixotic as the career it describes. Ominously subtitled "Volume One (1919-1955)", the book offers a profusion of the artist's juvenilia, paintings (including student copies of Renaissance works in the Met), minor illustrations, sheaves of wartime sketches, and letters to his wife, Natalie (who wrote the foreword), and even a reproduction of his college transcripts. This detailed sifting of the remains wouldn't seem like folly if the subject were, say, Jackson Pollock or some other fabled hero anointed by the Gods of Art History. The book is probably the one Bernard Krigstein would have wished for himself, but it is not the book he needs: a well-selected anthology culled from the couple of hundred comic-book stories he illustrated, mostly in the nineteen-forties and fifties. As it stands, the current book is best read as a poignant bildungsroman about a disappeared type: the mid-century lower-middle-class New York Jewish intellectual, drunk on art and culture, struggling to survive morally and aesthetically in the commercial wilderness.

"The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay," Michael Chabon's 2000 novel, reminds us that the early comic-book industry was a specifically Jewish milieu, virtually an extension of the rag trade. It was invented by a Jewish printing salesman and popularized with stories created by two Jewish kids from Cleveland about an immigrant from the planet Krypton. Many of the first generation of creators - like Will Eisner, Bob Kane (Kahn), Stan Lee (Lieber), and Jack Kirby (Kurtzberg) - were first- and second-generation New York Jews. And, while many of them were intelligent, very few were educated, and only Krigstein was a true intellectual. He would have had more in common with the staff of Partisan Review or Commentary than he did with his colleagues on Nyoka the Jungle Girl, Space Patrol, and Strange Tales of the Unusual.

Krigstein first heard what he later called "the sound of art" in junior high school. He opened a book on art appreciation and got bitten by one of Cézanne's apples. At Brooklyn College, his future wife persuaded him to switch his major from accounting and commit himself to becoming a "fine" artist. Economic need made Krigstein, like many other aspiring painters, stumble into comic-book work. Unlike the others, he began to sense the form's potential and, without condescension, put all his skill and insight into testing its limits. His paintings looked back to representational values that were at least fifty years out of date; his comics were visionary and looked ahead at least that far.

After he abandoned the field, in the nineteen-sixties (and was abandoned by it), he said, "I found that comics was drawing and... shed all criticism of the form as I worked in it." Usually hampered by banal scripts, Krigstein reflected:

My futile idea was that action in comics, as in any art, doesn't end with one person pounding another person in the jaw. There's also the action of emotion, psychology, character and idea. I yearned to have stories which dealt with more reality and people's feelings and thoughts... a kind of literary form, let's say even a Chekhovian form, where one could delve into real people and real feelings.

Manny Stallman, a more typical comic-book artist, once turned to Krigstein's brother in disbelief and said, "Bernie's actually taking this stuff seriously!"

Commercial art, for all its constraints, seemed like the only haven for figurative artists at mid-century, and Krigstein took a craftsman's pride in his accurate perspectives and his researched images based on observation. Without looking cramped, his well-balanced panels began to teem with crowds of individually articulated figures. He disdained shortcuts and easy solutions, and replaced the cartoonist's vocabulary of sweat marks and action lines with a painter's language of composition and form. It's as if the other cartoonists were expressively drawing Yiddish while Krigstein eloquently drew Hebrew.

Combative by nature, he fought the indifference and deadlines of the assembly-line shops for the right to ink his own panels. Astoundingly, at the zenith of the McCarthy era he led a battle to unionize freelance comic-book artists so they would all receive standardized rates, health benefits, and a modicum of respect. After his organizing efforts crumbled, in 1953, Krigstein had the good fortune to hook up with EC comics. The scripts were notches above the rest, and the outfit sought the best illustrators, encouraging them to develop individual approaches.

Nearing the height of his powers, Krigstein adjusted his style for each of the EC stories he was assigned: stately calligraphic panels influenced by Eastern art for adapting a Ray Bradbury fable set in ancient China; a scratchy German Expressionist approach for a story about an evil hypnotist seen from the murderer's point of view; crisp fifties modernism for the tale of a murderously curdled suburban marriage. All displayed Krigstein's cool intelligence and mastery. All were elegant - even beautiful - though somehow uningratiating. Highly respected by his EC peers, Krigstein was not a favorite with EC readers, who preferred Wally Wood's obsessively detailed rocket ships and Graham Ingels' fetid corpses.

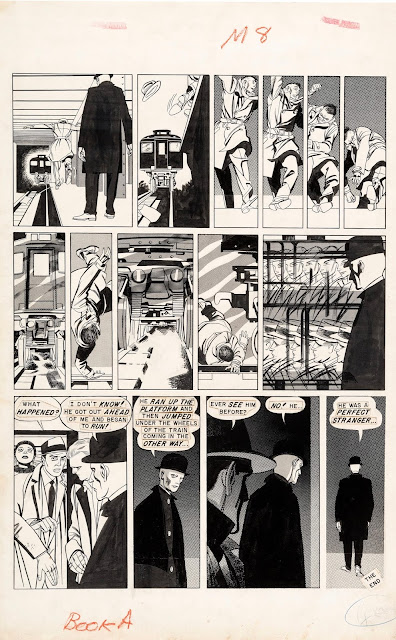

Krigstein began to vibrate with the inner language of comics, to understand that its essence lay in the "breakdowns," the box-to-box exposition that breaks moments of time down into spatial units. "It's what happens between these panels that's so fascinating," he said in a 1962 interview. "Look at all that dramatic action that one never gets a chance to see. It's between these panels that the fascinating stuff takes place. And unless the artist would be permitted to delve into that, the form must remain infantile."

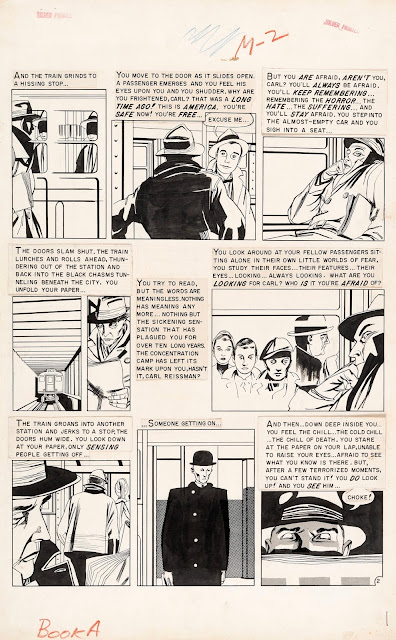

Krigstein became ravenous for more panels than the rigidly formatted short scripts permitted; he took to subdividing the pre-lettered art boards to allow more and more—albeit smaller and narrower—boxes on his pages. Then Al Feldstein, EC's primary editor and scriptwriter, assigned him a six-page story, "Master Race." A memory-haunted concentration-camp refugee, Carl Reissman, enters a subway car and recognizes the cadaverous stranger who sits across from him. A flashback details the horrors of the Third Reich and finally reveals that Reissman had been a perpetrator - the commandant of a death camp. The stranger chases him down an empty platform, where Reissman slips and is crushed by an onrushing train. Whether the mysterious stranger was a former victim who once swore revenge or a projection of Reissman's guilt is left unresolved.

Feldstein thought of this as one more "snap-ending" story patterned after O. Henry, much like the three others he cranked out each week. It just so happened that this one was about the Nazi death camps and postwar guilt at a time when the culture was unwilling to reckon with the catastrophe in any medium. Krigstein seized on the script as a chance to demonstrate his own and the medium's possibilities. He begged for twelve pages and was begrudgingly granted eight.

Krigstein's formal qualities as a storyteller—not the story's subject matter - make Master Race a tour de force. He encapsulates the decade of Nazi terror powerfully but with restraint, never slipping into the Grand Guignol that made EC notorious. The two tiers of wordless staccato panels that climax the story have become justly famous among the comics literate. They have often been described as "cinematic," a phrase thoroughly inadequate to the achievement: Krigstein condenses and distends time itself. The short chase that ends Reissman's life takes up about the same number of panels given over to the entire Hitler decade; Reissman's life floats in space like the suspended matter in a lava lamp. The cumulative effect carries an impact - simultaneously visceral and intellectual - that is unique to comics.

Hardly anyone noticed the story, published in Tales Designed to Carry an IMPACT #1. It was barely distributed, lost in the aftermath of the devastating 1954 Senate investigation into the relationship between reading comic books and juvenile delinquency. As EC and the rest of the comics industry evaporated around him, Krigstein briefly went to work in his father's dress factory. After several months of filial squabbles, he turned to freelance magazine, book, and record-jacket illustration, where his integrity and his contentiousness eventually limited his success. He vainly tried to interest book publishers in a massive comics adaptation of "War and Peace," but by 1962 had settled into a twenty-year career teaching illustration at New York's High School of Art and Design, to subsidize his devotion to painting.

I was a cartooning major at Art and Design in 1963. Only vaguely aware of Krigstein's comics, I gave him a wide berth. He was a small, barrel-chested man with a reputation among my illustration-major friends as a tough teacher, humorless and completely dismissive of comics. I was delighted to learn from Sadowski's book that the initials Krigstein used when signing his early superhero pages, "B. B. Krig," stood for the nickname he had earned in the Army: Ballbuster.

I met him only once, in the early seventies. John Benson, the editor of an EC fanzine called Squa Tront, wanted to expand and publish a panel-by-panel analysis of Master Race that I had written in 1967 as a college term paper. We went to visit Krigstein at his painting studio, on East Twenty-third Street, so I could read it to him and get his responses. Krigstein at first demurred that those days were long behind him and he didn't remember much about the work. As I began reading, he entered into the analysis avidly, acknowledging a reference to Futurism in one panel, to Mondrian in another, denying a reference to George Grosz in yet another. He basked when I pointed to a visual onomatopoeia that conjured up a subway's rumble. It was as if messages he'd sent off in bottles decades earlier had finally been found.

At the end of the paper, I had compared his approach to that of some important contemporaries whom I also admired, including Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner. When I read that paragraph, Krigstein darkened. "Eisner!" he shouted. "Eisner is the enemy! When you are with me, I am the only artist!" He yanked me further into his studio and pointed at the walls. "Look!" he roared. "You see these paintings?" I saw several large, molten, and lumpy Post-Impressionist landscapes in acidic colors. "These are my panels now!" His voice betrayed all the anguish of a brokenhearted lover.

© Art Spiegelman