The book collects four tales of urban life in a seamless blend of social realism and melodrama. Set in the same building in a New York Jewish ghetto, these stories fictionalise events Eisner remembers happening around him during his childhood.

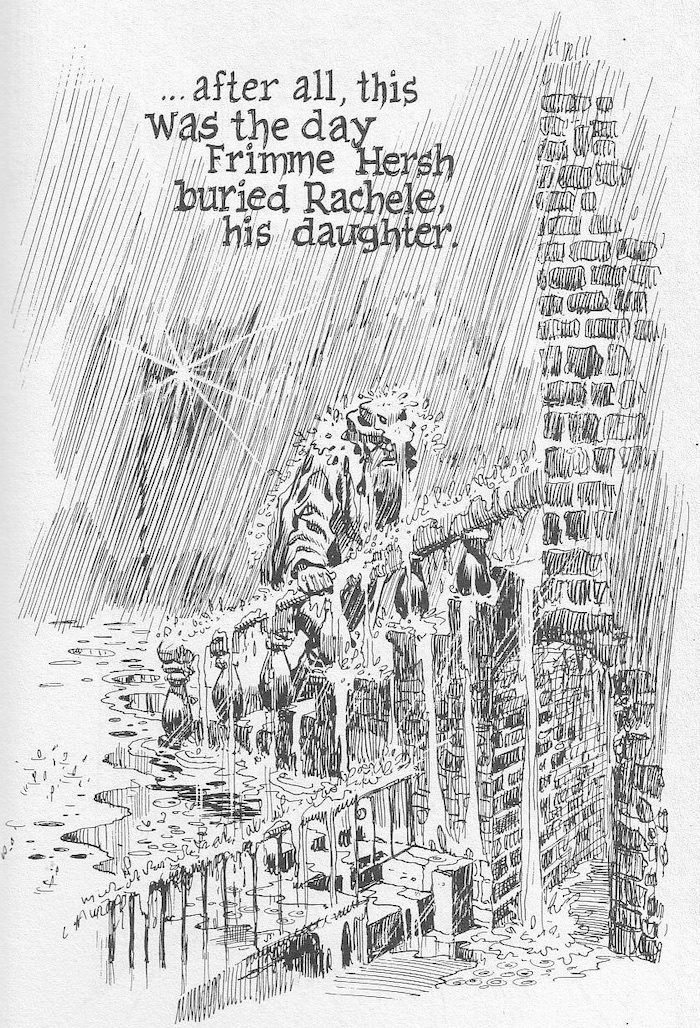

In the title piece, Frimme Herch believes he is favoured by God until the death of his daughter, which he interprets as God's betrayal. Herch becomes a financial success, but his loss of faith prevents him from happiness. In an ironic twist, Herch regains his faith but is them seemingly struck down by a God angered at Herch's presumptions.

In The Street Singer, a failed opera diva seduces the title character and plans to live out her failed dreams by guiding the younger man's career. The two are clearly using one another for their own purposes but manage to give one another hope in their otherwise bleak lives. Born losers, the star crossed pair become lost from one another in the big city and never get the opportunity to pursue their dreams.

The Super manages to arouse sympathy for the grouchy, porn-addicted building manager who lusts after a young tenant. Eisner is not interested in heroes or villains, and the characteristics which would make the man repugnant in most stories are coupled with vulnerability and humanity.

In the final story, Cookalein, Eisner casts his sympathetic eye for human foibles on a group of urban residents summering in the country who grope about in clumsy searches for love, sex and social advancement.

The specificity of setting lends authenticity to the universality of Eisner's concerns, which include love, loss, alienation, hope and despair. Eisner's formal creativity and mastery of atmosphere invest these tales with emotional power. The novelty of the format aside, A Contract With God is a moving and compelling book, and the masterpiece of one of the medium's first true artists.

WILL EISNER:

(discussing the death of his daughter Alice from leukaemia)

My grief was still raw. My heart still bled. In fact, I could not even then bring myself to discuss the loss. I made Frimme Hersh’s daughter an “adopted child.” But his anguish was mine. His argument with God was also mine. I exorcised my rage at a deity that I believed violated my faith and deprived my lovely 16-year-old child of her life at the very flowering of it.

REVIEW BY FRANK MILLER:

(from an interview in The Comics Journal #209, December 1998)

Well, a lot of it to me gets back to Eisner. He still in many ways is a framework for me, and I think at least to date, probably the most important piece of work he did was A Contract With God. Certainly in terms of influence, because I wasn't the only one who sat up and took notice when that book came out. It had a profound effect on how I approached not just the fate of my work, but the kind I wanted to do. I wanted to work much more long form. That's ironic, because it was a series of short stories. But I think he quietly started a revolution. He's been relentless in pursuing it.

REVIEW BY SCOTT McCLOUD:

(from the introduction to the 1997 edition of A Contract With God)

I’m writing this in 2016, more than a decade after Will Eisner died. The potential of comics is being demonstrated daily in ways Eisner anticipated when he created A Contract With God nearly forty years ago, but also in ways he could’ve hardly imagined. And of course, inevitably, the book itself will suffer the fate of any first-of-its-kind pioneer. It’s been joined now by so many of its kind that it’s easy to lose it in the crowd. There are now graphic novels with ever more complex formal ambitions, with subtly written dialogue, up-to-date sensibilities, pitch-perfect irony, and politically urgent subject matter. Graphic novels proliferate and improve with every passing year. But they’re still branches on an immense family tree that was once just a sapling - planted in soil he always knew was fertile.

REVIEW BY DAVE SIM:

(from an interview in The Comics Journal #83, August 1983)

I kept putting off buying A Contract With God for a long time because I knew it would be a long time before I saw another Contract With God, and when I read it, it was just like, Oh, if there were only 18 things coming out like this.

REVIEW BY CHESTER BROWN:

(from an interview in The Comics Journal #135, April 1990)

Another bridge type book was A Contract With God by Will Eisner, which I picked up when it first came out back in '79... it was an important book too, in making me see that there were other types of ways of doing comics. There were other kinds of comics that were possible... here he was doing something different, and something that wasn't about a character with a mask on his face. That was neat stuff, and kind of eye-opening at the time.