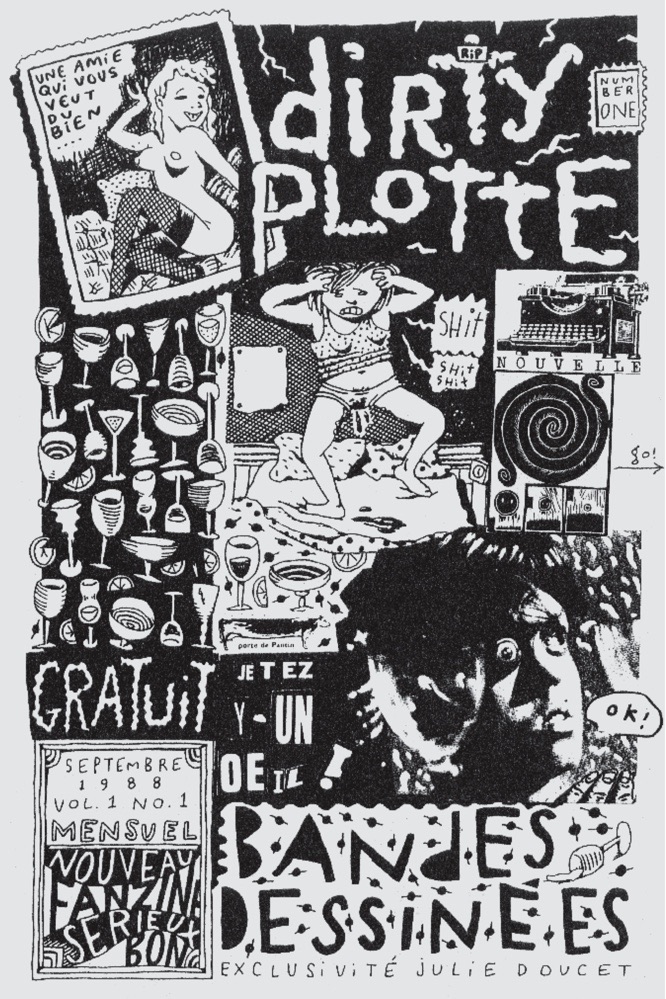

I first encountered Julie Doucet’s comics at a crucial time in my life, when the superhero comics I’d grown up with had finally, completely lost their appeal, but the far-fetched dream of becoming a cartoonist persisted. I know I was in high school at the time, so I’m guessing it was probably around 1989 or 1990. Based on Chester Brown’s glowing recommendation in his comic Yummy Fur, I sent some cash to Julie’s Montreal address, and a few weeks later I received a meticulously hand-crafted packet of her comics. I had seen a few minicomics at that point, but something about Julie’s in particular had a huge impact on how I thought about comics and, on a broader scale, what I wanted to do with my life.

Aside from being shocking, funny, and beautiful, those early Dirty Plotte minicomics were inspirational because they made cartooning seem both attainable and impossible. The fact that they were so clearly hand-made, by one artist with a one-of-a-kind vision of the world, gave the teenage version of me that wonderfully narcissistic feeling of “Hey, maybe I could do this, too!” That the stories themselves were deeply personal, quotidian, dream-based, and concise only added to that admittedly arrogant but exhilarating feeling. And the fact that the art, the language, the stories felt so new (and in some ways alien) to me made it clear that comics as a medium had infinite possibilities, and that as much as I tried, I could never even come close to what Julie was doing. That was exhilarating in its own way, especially for a kid who, only a few years prior, had no greater ambition than to “draw comics the Marvel way.” There was no going back to superheroes after that, and it wasn’t long before I was printing copies of my first minicomic at the local Kinko’s.

I followed Julie’s ensuing career closely, tracking down and collecting her work wherever it appeared. The evolution of her art and writing through the years that Drawn & Quarterly was publishing Dirty Plotte was staggering. The release of each issue felt like a new album from a favorite band. It was an event. Every development in her drawing style or her storytelling or her sense of design was thrilling, and impossibly, it all kept getting better.

Even fifteen years after she unofficially retired from comics, I still think of Julie as kind of the platonic ideal of a cartoonist. Visually, her work is complex, meticulous, wild, and thoroughly alive, simultaneously building upon and departing from comics orthodoxy. Her style is at once haunting and sweet, beautiful and grotesque, but also completely, indisputably original. Every line, every detail, every person, even every coffee pot is a part of Julie’s universe. The stories, while often dreamlike or even nightmarish, are brilliantly readable, depicting and evoking a wide range of moods and emotions. Even her most mundane story is revelatory by virtue of its specificity, its language, its eccentricity. Most importantly, her comics are self-expression in its purest form, and that, to me, is the greatest possible use of the medium. At this point in her incredible artistic evolution, I’m not sure that Julie would take this as a compliment, but I still think of her as that increasingly rare thing: a natural-born cartoonist, who, when she puts pen to paper, just somehow instinctively does everything right.

I first met Julie in person more than twenty years ago, and we’ve crossed paths a handful of times since then. But to be honest, I don’t feel like I know her that well. I’ve had the good fortune of becoming friends with many of my favorite cartoonists, and while I treasure those relationships, there’s something great about the fact that Julie Doucet is still this mythic force, somewhere far away, creating art that only she could make. Almost thirty years after receiving that packet of minicomics in the mail, I’m a fan, and I’m eternally grateful for that experience.

This essay is taken from Dan Nadel's "The Julies" article which appeared in Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, published by Drawn & Quarterly in 2018. Read Dan's complete essay here...