The Sketchbooks of Robert Crumb (1964 to present)

REVIEW BY GARY GROTH:

Robert Crumb has maintained sketchbooks, which he has written and drawn continually, from the early '60s to present. Seven large, hardcover volumes have appeared from the German publisher 2001 printing sketches datings from 1967, with the most recent one (published November 1998) running up to 1996, representing 29 years and nearly 3,000 pages of facsimile reproduction. Fantagraphics Books (conflict of interest alert!) has published six R. Crumb Sketchbooks to date, which begin three years earlier than [publisher] 2001's (1964) and include more pages from the artist's sketchbooks in the years that 2001 has published. The US editions of the sketchbooks from 1964 to 2000 will comprise over 4,000 pages.

The very conception of a single, unified, organic (and ongoing) life's work, as this is, like Crumb's individual stories and his work generally, sui generis: it is not merely inconceivable that no other artist has felt the inner need to consistently draw in a sketchbook for over 35 years (and counting), but an immutable fact. Not only has no cartoonist done so but I am aware of no artist who ever has (Frida Kahlo's drawn diaries come the closest, but not very); in fact, these sketchbooks are, as a body of work, incomparable in their magnitude, scope and intensity, and there in lies their uniqueness and, in part, their value. (We may assume that other, invariably lesser, artists will follow Crumb's example in the future, of course).

Crumb then, has created an entirely new "genre", but how does one describe it? It is not autobiography in any recognisable or understood sense; it is not a systematic or linear iteration of important professional and personal details, there is none of the "objectivity" we associate with biography such as the customary citation of names, dates, places and so forth. It is, therefore, not so much a chronicle of a life than a chronicle of a life of perceptions, which is of considerably greater aesthetic interest.

What differentiates the sketchbooks from Crumb's finished comics work is that the wedding of perception and technique achieves a degree of purity that the considered and necessarily cohering choices of tonality, style, structure, etc, tend to dilute. It is, among other things, a raw insight into process: how are ideas formed, how are connections made, how is technique and craft honed, how is the ability to truly see cultivated? Art is always mediated by artifice and every artist, no matter how self-revealing or self-lacerating, wears a mask that separates himself from his work. The cumulative effect of these sketchbooks is to narrow the gap between the artist and his art, or, put another way, to create such an intimacy as to render the profound connection between art and humanity palpable.

It also stands as a monumental existential document. Crumb repeatedly expresses, through a variety of penetrating and coruscating visual metaphor, the central existential struggle: to live in the full light of consciousness with all the risk, pain, and suffering that entails.

One can practically become lost in the onrush of caricatures, impeccably rendered portraits, formal practice (such as when Crumb was learning to use a brush in the early '80s), intense self-scrutiny, excerpts from various authors, screeds, comic strips, roughs for strips that never appeared, a visual playfulness that one rarely sees in his comics after 1970, stunning displays of virtuoso draftsmanship, the occasional abstract or surreal vista, diary-like entries (such as one agonising over his relationship with his son Jessie), heart-breaking depictions of his daughter Sophie, worshipful drawings of his wife Aline, his sensual supple line and mastery of form, humour, seriousness, empathy, misanthropy, goofing off and self-flagellating anguish - in short, the full panoply of a life of perceptions rendered with consulate artistry.

ALAN MOORE:

(from an article in The Life & Times Of Robert Crumb)

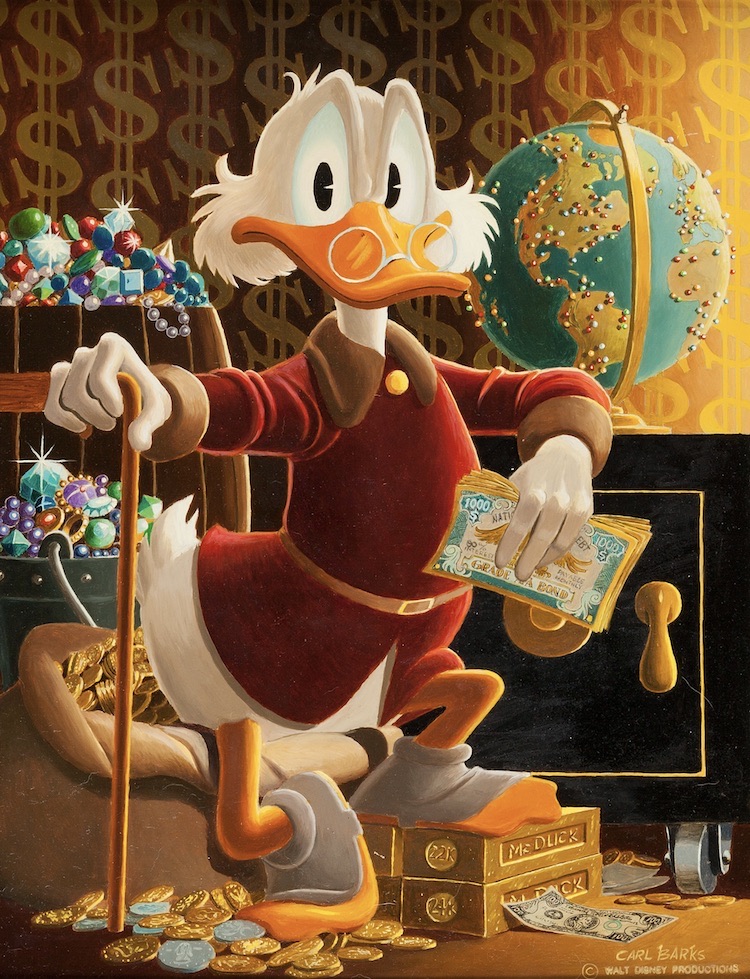

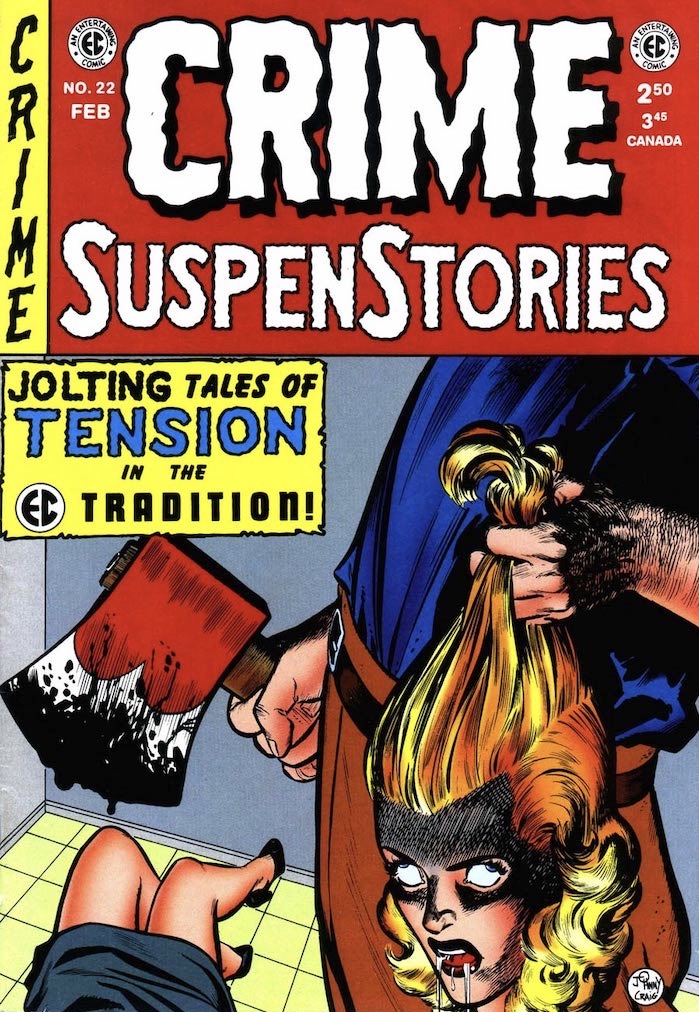

Crumb's earliest work shows a youthful sense of delight and exuberance, a sense of glee to be working in the comic medium with access to all its varied icons and delights. The characters in the early pieces, however weird or macabre or ridiculous, seem to be purposefully two-dimensional comic characters... His grotesque pranks are told in the same way that any animated character's more innocuous japes would be presented, right down to the sense of a winking camaraderie with the reader in the final panels. In Crumb's piece, though, turning it into something dark and different, raising all sorts of new and unsettling questions about the nature of the form itself... But there was a gradual sense, at least as I saw it, of Crumb becoming impatient or weary with simply subverting the cartoon icons of his youth. It looked as if he felt the need to grow and was looking around for territory to grow into... In his work for Arcade, we see Crumb confidently striking out for new pastures with an assurance that shows in every line... I'd scarcely recovered from the hard, no-nonsense pessimism of Crumb's look at life in This Here Modern America when along came his powerful and affecting portrait of an early backwoods man, That's Life. This piece, which manages to chart the rise and fall of a whole section of the music industry while telling a powerful human story is, I think, one of the best things that Crumb has ever done. A sad and bitter indictment, it is nevertheless accomplished with a real human warmth... Take a look at his sketchbooks and see just how much he's capable of caring about a stack of firewood or the light on his wife's forehead or a corner of his backyard, and if that doesn't make you feel better about the world we live in, then get a friend to try holding a mirror under your nose.

FURTHER READING: