TCJ Article: Another Look at Bill Mauldin (2021)

10 August 2021

The Willie & Joe Cartoons by Bill Mauldin (No. 85)

TCJ Article: Another Look at Bill Mauldin (2021)

09 August 2021

The Idiots Abroad by Gilbert Shelton & Paul Mavrides (No. 44)

What starts as an innocent trip to score cheap dope leads to a worldwide Freak diaspora. Fat Freddy is abducted by soccer players and travels throughout Europe being chased by terrorists (who are in turn pursued by the American military), befriending the eccentric genius Pablo Pegaso and searching desperately for decent American food. Freewheelin' Franklin heads to Central America where he deals with survivalists, banana republic dictators and pirates. And in the genius stroke that would eventually tie together the chaos, Phineas heads to the Middle East and becomes the head of a worldwide religion movement called Fundaligionism ("It sounds like fun... it has a fund... it's got that old time 'legion...") whose followers sing out, "Hallelujah-gobble!"

The counterculture paranoia for authority rings true as greed - for money, power, soccer-shaped bombs - is renewed ridiculously threatening and taken to the illogical extreme of a New World Order government. The notion that organised religion is the tool of an international shadow cabinet has been expressed before (often by those with the same recreational habits as the Freaks), but Shelton has a gift for taking such conspiracy theories and making then hilarious extensions of his characters. As do all great satirists, he doesn't play fair with his targets but shows why fairness wouldn't make any sense anyway. Moreover, his delight in putting his main trio through their paces remains unabated: somehow, the Freak Brothers continue to amuse with their individual quirks and idiocies. Though Phineas turns Freddy and Franklin into the ultimate Renaissance men, the duo turn their back on the Freak World Order and bring the complex weave of plot lines to a glorious crashing finale. The Freaks shall Freaks remain, it would seem - and hopefully will continue to be counterculture throwbacks well into the next millennium. Hallelujah-gobble, indeed.

08 August 2021

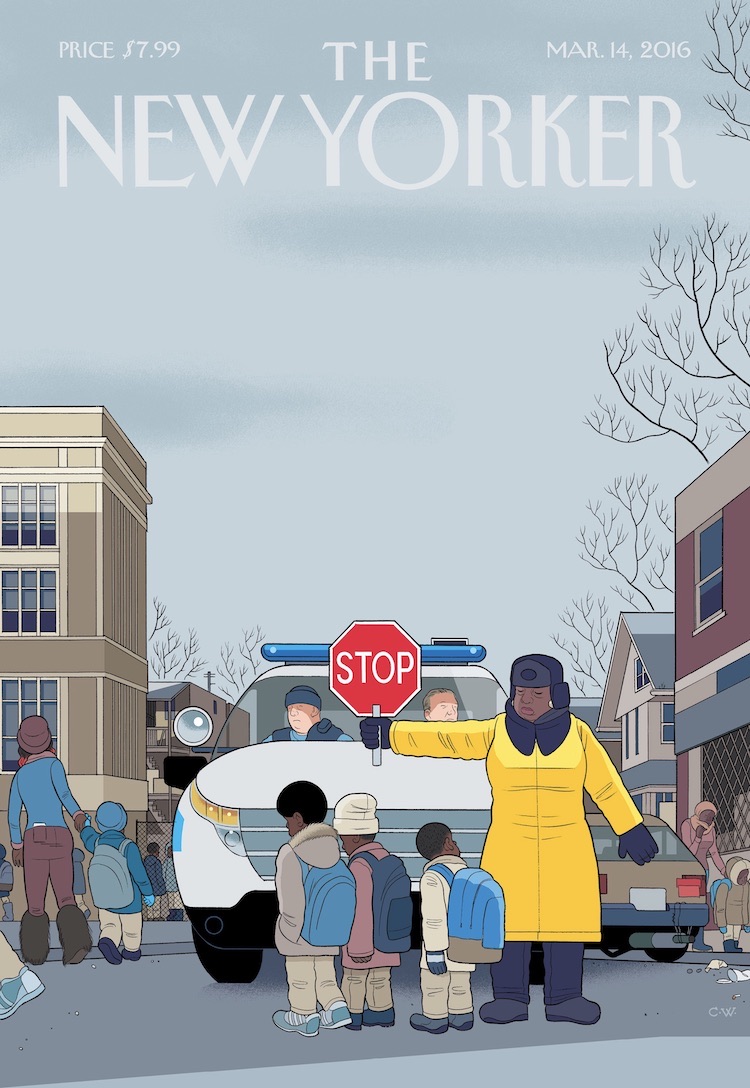

Covering The New Yorker: Chris Ware

Having lived in Chicago for thirty years, I’ve only ever been a visitor to New York, but I love it like no other city. Teeming with unpredictable people and unimaginable places and unforeseeable moments, life there is measured not in hours but in densely packed minutes that can fill up a day with a year’s worth of life. Lately, however, closed up in our homes against a worldwide terror, time everywhere has seemed to slur, to become almost Groundhog Day-ish, forced into a sort of present-perfect tense - or, as my fellow New Yorker contributor Masha Gessen more precisely put it, ‘loopy, dotted, and sometimes perpendicular to itself.’ But disaster can also have a recalibrating quality. It reminds us that the real things of life (breakfast, grass, spouse) can, in normal times, become clotted over by anxieties and nonsense. We’re at low tide, but, as my wife, a biology teacher, said to me this morning, ‘For a while, we get to just step back and look.’ And really, when you do, it is pretty marvellous.

As the resident stay-at-home cartoonist, stay-at-home dad and stay-at-home laundress of my family, I knew some paradigm had shifted when I could no longer tell my wife’s clothes from my daughter’s. Soon, shirts were being traded. Then shoes. Sounds of footsteps on the stairs became indistinguishable, and I found I had to wait to adjust my speaking tone to see whom I was scolding for not hanging up a sweater. Five years - only five years! - since I was helping my daughter into a bike seat to take her to second grade, and now I could barely kiss the top of her head, though she could now kiss my wife’s. It’s cliché and it’s sentimental but it’s true: parents, when your child asks, “Will you play with me?” - do. Because one day they really will stop asking, just like you did.

I lived in San Antonio in high school, in the mid-nineteen-eighties, and attended college in Austin, occasionally driving to Houston with my fellow art students to visit museums, and sometimes alone, just for the change of scenery. I liked Houston for its big buildings, its diversity, and its slack zoning laws, which made neighborhoods unpredictable and surprising. One night, my cartoonist friend John Keen and I stopped at a restaurant-bar that was about halfway to Houston, in the very Texas-sounding town of Winchester. The parking lot was locked and loaded with about two dozen pickup trucks, and, as scrawny liberal Austinites, we braced ourselves and pushed open the saloon doors, only to find black and white farmers talking and laughing, playing poker, and shooting pool together. In a corner, an interracial couple quietly ate barbecue. This Winchester bar, we realized, was more integrated than the University of Texas we’d just left.

Most mornings, after I drop my eleven-year-old daughter off at school in Oak Park, Illinois, I drive my wife to the west side of Chicago, where she works as a teacher in a public school. Along the way, we’ll frequently pass a few of her students waiting for the bus, huddled in hoodies with their backward backpacks and my wife 0 it’s against Chicago Public School policy for a teacher to offer rides to students - will recognize and wave at many of them, citing an affectionate anecdote (“He’s one of the smartest students I’ve ever had”) or a bracing detail (“She beat up her boyfriend”) or a horrifying story (“His brother got shot”).

Stationed among these students are the crossing guards, all of whom are Chicago Police employees. In the outer peripheries work the Safe Passage guards, hired by the city when fifty schools were closed in 2013, lengthening the daily walks, drives, and bus rides of thousands of students to reassigned schools through neighborhoods identified as gang territory, just because they have streets and corners. Nearly all of the Safe Passage guards are middle-aged African-American women, and they nearly all recognize us and wave and smile, braving icy temperatures for hours every winter morning and afternoon. Our favorite is an energetic lady who spins around and sings to herself in the middle of the street, luring and halting traffic with graceful pirouettes that make it look as if she’s controlling the cars as part of some larger, secret ballet. However, she can turn on the cars just as easily: we’ve seen her scream at disobeying drivers, smacking her stop sign on the pavement with rage. Once, she even yelled at me, tearing through the fabric of our years-long silent code of friendship, when I guess I didn’t slow down fast enough.

Last week, as we gingerly crept through her intersection, my wife noted the sorry state of her sign, new at the beginning of the school year but now showing its battle damage: the top chipped, bent and curled down nearly halfway through the lettering, the consequence of it being slammed to the ground, over and over.

The New Yorker is arguably the primary venue for complex contemporary fiction around, so I often wonder why the cover shouldn’t, at least every once in a while, also give it the old college try? In the past, the editors have generously let me test the patience of the magazine’s readership with experiments in narrative elongation: multiple simultaneous covers, foldouts, and connected comic strips within the issue. This week’s cover, “Mirror,” a collaboration between The New Yorker and the radio program “This American Life,” tries something similar. Earlier in the year, I asked Ira Glass (for whose 2007-2009 Showtime television show my friend John Kuramoto, d.b.a. “Phoobis,” and I did two short cartoons) if he had any audio that might somehow be adapted, not only as a cover but also as an animation that could extend the space and especially the emotion of the usual New Yorker image. I knew that Ira was the right person to go to with this experiment in storytelling form, because he’s probably one of the few people alive making a living with a semiotics degree.

So he sent me an audio story, and, after coming up with a cover image based around it, I set to work with John Kuramoto to somehow animate it. Usually, when listening to a story, one’s mind not only sees but also feels in images; you imagine and constantly revise and update entire tableaux, much the way you imagine things while reading a book. I hoped that our pictures wouldn’t interfere with that ineffable mental dance but would somehow, like my usual medium of graphic novels, complement it. In fact, it seems to me that much of what we “see” in our everyday lives isn’t in front of us at all but within our memories and imaginations. I’ve noticed as my daughter Clara has grown older that the unfocussed “not seeing what’s in front of her because she’s lost in thought” look has become, perhaps sadly, more and more common. Then again, it’s what I do all day.

In the weird synchrony of life imitating art (or at least of life imitating half-finished New Yorker covers), this year ten-year old Clara’s Halloween costume employed as its crucial component the application of “scary/sexy” makeup. You know - black lipstick, green eye shadow. Though it was a sinister look, her strategy had an innocent purpose: she just wanted to try on lipstick. Worried, I did some intel with the local moms and discovered, not surprisingly, that this same costume idea seemed to be a coördinated plan within many of the pre-teen sleepover cells in our neighborhood. But I wasn’t ready for this moment, and neither was my wife; for years, my daughter had yelled at her mom for putting on lipstick because it made her “look fake.” But now, dear God, she wanted to see what it looked and felt like herself - the first application of a fiction to mask her remaining few months of childhood. This led to some convoluted car discussions. “Dad, if you say women are doing it just to accommodate men, then what are men doing to accommodate women? You’ve always said women can do anything men can, right? So, as a woman, I want to wear makeup!” And so on. But - point taken.

The question was complicated even further when, in a chat with a friend, I grumbled, like lots of people at the time, about Hillary Clinton’s seemingly tone-deaf statements about her use of a private e-mail server. “Why can’t she just apologize and play nice?” I pleaded. My female friend, taking a moment, offered, “Well, as a woman she’s being held to a different standard.” Point taken, again. The adage about working twice as hard for half as much. Or: maybe I’m just not as great a guy as I thought I was.

Of course, the most important people here are the subjects of the story: Hanna Rosin (the co-host of NPR’s “Invisibilia” and a writer for the Atlantic and Slate) and her daughter, and they are not at all fictional. But the interpretations that John and I have provided more or less are. Thus, my apologies and thanks to Hanna and her daughter both for any and all liberties taken. The video’s music, by Nico Muhly, was composed and performed especially for this cartoon, so most grateful regards to him as well and to the musicians who recorded it: Nathan Schram, on viola, and Fritz Myers, on piano.

07 August 2021

Tantrum: An Appreciation by Neil Gaiman

"Whatever that word 'love' means --" says the baby, essaying its first steps, "I can hardly wait till I'm big enough to do it to them."

When I first discovered Jules Feiffer I was... what? Four years old? Five, maybe. This was in England, in 1964 or 1965, and the book was a hardback blue-covered edition of The Explainers, Feiffer's 1962 collection, and I read it as only a child can read a favourite book: over and over and over. I had little or no context for the assortment of losers and dreamers and lovers and dancers and bosses and mothers and children and company men, but I kept reading and rereading, trying to understand, happy with whatever comprehension I could pull from the pages, from what Feiffer described as "an endless babble of self-interest, self-loathing, self-searching and evasion.” I read and reread it, certain that if I understood it, I would have some kind of key to the adult world.

It was the first place I had ever encountered the character of Superman: there was a strip in which he "pulled a chick out of a river" and eventually married her. I'd never encountered that use of the word 'chick' before, and assumed that Superman had married a small fluffy yellow baby chicken. It made as much sense as anything else in the adult world. And it didn't matter: I understood the fundamental story -- of compromise and insecurity -- as well as I understood any of them. I read them again and again, a few drawings to a page, a few pages to each strip. And I decided that when I grew up, I wanted to do that. I wanted to tell those stories and do those drawings and have that perfect sense of pacing and the killer undercut last line.

(I never did, and I never will. But any successes I've had as a writer in the field of words-and-pictures have their roots in poring over the drawings in The Explainers, and reading the dialogue, and trying to understand the mysteries of economy and timing that were peculiarly Jules Feiffer's.)

That was over thirty years ago. In the intervening years the strips that I read back then, in The Explainers, and, later, in discovered copies of Sick, Sick, Sick and Hold Me!, have waited patiently in the back of my head, commenting on the events around me. ("Why is she doing that?" "To lose weight."/ "You're not perfection... but you do have an interesting off-beat color... and besides, it's getting dark."/ "What I wouldn't give to be a non-conformist like all those others."/ "Nobody knows it but I'm a complete work of fiction")

So. Time passed. I learned how to do joined-up writing. Feiffer continued cartooning, becoming one of the sharpest political commentators there has ever been in that form, and writing plays, and films, and prose books.

In 1980, I got a call from my friend Dave Dickson, who was working in a local bookshop. There was a new Jules Feiffer book coming out, called Tantrum. He had ordered an extra copy for me.

I had stopped reading most comics a few years earlier, limiting my comics-buying to occasional reprints of Will Eisner's The Spirit. (I had no idea that Feiffer had once been Eisner's assistant.) I was no longer sure that comics could be, as I had previously supposed, a real, grown-up, medium. But it was Feiffer, and I was just about able to afford it. So I bought Tantrum and I took it home and read it.

I remember, mostly, puzzlement. There was the certainty that I was in the presence of a real story, true, but beyond that there was just perplexity. It was a real 'cartoon novel'. But it made little sense: the story of a man who willed himself back to two-years of age. I didn't really understand any of the whys or whats of the thing, and I certainly didn't understand the ending.

(Nineteen is a difficult age, and nineteen year-olds know much less than they think they do. Less than five year olds, anyway.)

I was at least bright enough to know that any gaps were mine, not Feiffer's, for every few years I went back and re-read Tantrum. I still have that copy, battered but beloved. And each time I re-read it, it made a little more sense, felt a little more right.

But with whatever perplexity I might have originally brought to Tantrum, it was still one of the few works that made me understand that comics were simply a vessel, as good or bad as the material that went into them.

And the material that goes into Tantrum is very good indeed.

I re-read Tantrum a month ago.

Now, as I write this, I'm in spitting distance of Leo's age, with two children rampaging into their teens: I know what that place is. And I have a two-year old daughter -- a single-minded, self-centred creature of utter simplicity and implacable will.

And as I read it I found myself understanding it -- even recognising it -- on a rather strange and personal level. I was understanding just why Leo stopped being 42 and began being two, appreciating the strengths that a two year old has that a 42 year old has, more or less, lost.

Leo's drives are utterly straightforward, once he's two again. He wants a piggy back. He wants to be bathed and diapered and fussed over. As a 42 year old he lived an enervated life of blandness and routine. Now he wants adventure -- but a two year old's adventure. He wants what the old folk-tale claimed women want: to have his own way.

Along the way we meet his parents, his family, and the other men-who-have-become-two-year-olds. We watch him not burn down his parents' home. We watch him save a life. We watch his quest for a piggy-back and where it leads him. The story is sexy, surreal, irresponsible and utterly plausible.

Everyone, everything in Tantrum is drawn, lettered, created, at white hot speed: one gets the impression of impatience with the world at the moment of creation -- that it would have been hard for Feiffer to have done it any faster. As if he were trying to keep up with ideas and images tumbling out of his head, trying to capture them before they escaped and were gone.

Feiffer had explored the relationship between the child and the man before, most notably in Munro, his cautionary tale of a four-year old drafted into the US army (later filmed as an Academy Award-winning short). Children populated his Feiffer strip, too -- not too-smart, little adult Peanuts children, but real kids appearing as commentators or counterpoints to the adult world. Even the kids in Clifford, Feiffer's first strip, a one-page back-up to The Spirit newspaper sections, feel like real kids (except perhaps for Seymour, who, like Leo, is young enough still to be a force of nature).

Tantrum was different. The term ‘inner child’ had scarcely been coined, when it was written, let alone debased into the currency of stand-up, but it stands as an exploration of, and wary paean to the child inside.

When the history of the Graphic Novel (or whatever they wind up calling long stories created in words and pictures for adults, in the time when the histories are appropriate) is written, there will be a whole chapter about Tantrum, one of the first and still one of the wisest and sharpest things created in this strange publishing category, and one of the books that, along with Will Eisner's A Contract With God, began the movement that brought us such works as Maus, as Love and Rockets, as From Hell -- the works that stretch the envelope of what words and pictures were capable of, and could not have been anything but what they were, pictures and words adding up to something that could not have been a film or a novel or a play: that were intrinsically comics, with all a comics' strengths.

I am delighted that Fantagraphics have brought it back into print, and, after reading it, I have no doubt that you will be too...

ⓒ Neil Gaiman

Keep up to date with all things 'Neil Gaiman' related here...

06 August 2021

Go Visit A Comic Exhibition in August!

UNITED KINGDOM:

Raymond Briggs: A Retrospective

Never-before-seen material from Briggs’ personal archive, revealing the origins of Ug, Ethel & Ernest, Fungus the Bogeyman and The Snowman, featuring over 100 original artworks. More details...

Where: Winchester Discovery Centre, Winchester, Hampshire

When: Now until 18 August 2021

Dave McKean: Imaginings

An exhibition of work by acclaimed artist and film maker Dave McKean, featuring a large selection of work, much of which has never been shown before. More details...

Where: Adam's Gallery, Reigate, Sussex

When: Now until 29 August 2021

Kane & Able

Original art and prints from the latest Image Comics collaboration between Shakey Kane and Krent Able. More details...

Where: Orbital Art Gallery, London

When: Now until 31 August 2021

Quentin Blake and John Yeoman: 50 Years of Children’s Books

A celebration of over 40 books created by Quentin Blake with writer John Yeoman. More details...

Where: Derby Museum & Art Gallery, Derby

When: Now until 3 October 2021

Black Panther & The Power of Stories

Three iconic costumes from Marvel Black Panther film - T’Challa, Shuri and Okoye - sit alongside Marvel comics, historic museum objects and local stories. More details...

Where: Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich

When: Now until 24 October 2021

V For Vendetta: Behind The Mask

This major new exhibition invites you to step inside the story and characters of one of the world’s most iconic graphic novels: V for Vendetta. Featuring original artwork by David Lloyd. More details...

Where: The Cartoon Museum, London

When: Now until 31 October 2021

Drawing Life

A new display showcasing the very best of the Cartoon Museum collection of cartoon art, curated by Guardian cartoonist and Cartoon Museum Trustee, Steve Bell. More details...

Where: The Cartoon Museum, London

When: Now until 31 December 2021

The Political Comics & Cartoons of Martin Rowson

Featuring Rowson’s most powerful political cartoons, caricatures and comics from the past forty years. More details...

Where: Kendel, Cumbria

When: 15 October to 5 November 2021

Beano: The Art of Breaking The Rules

Come face-to-face with the Beano gang through original comic artwork and amazing artefacts, plundered from the Beano’s archive. More details...

Where: Somerset House, London

When: 21 October 2021 to 6 March 2022

NORTH AMERICA:

Dave McKean: Black Dog

Dave McKean drawings from his 2016 graphic novel Black Dog which form a dream-like psychological portrait of British landscape and wartime artist Paul Nash. More details...

Where: Philippe Labaune Gallery, New York

When: Now until 14 August 2021

Three With a Pen: Lily Renée, Bil Spira & Paul Peter Porges

Featuring works by the three Jewish artists driven from their homes in Vienna after the German annexation of Austria, the so-called “Anschluss,” in 1938. More details...

Where: Austrian Cultural Forum, New York

When: Now until 3 September 2021

Hometown Heroes: Steve Ditko

A retrospective exhibit of the legendary Steve Ditko’s career, with original works, production art, prints and memorabilia. More details...

Where: Bottleworks, Johnstown, PA

When: Now until 11 September 2021

Drawn to Combat: Bill Mauldin & The Art of War

A retrospective of the provocative work by two-time Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin about a nation’s time of war, civil rights, and social justice. More details...

Where: Pritzker Military Museum, Chicago

When: Now until Spring 2022

Chicago: Where Comics Came to Life - 1880 To 1960

Curated by Chris Ware, and Chicago Cultural Historian, Tim Samuelson, this exhibition is a historical companion to the concurrently appearing survey of contemporary Chicago comics at the MCA. More details...

Where: Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago

When: Now until 3 October 2021

Chicago Comics: 1960s To Now

Telling the story of the art form in the influential city through the work of Chicago’s many cartoonists: known, under-recognized and up-and-coming. Featuring Chris Ware, Lynda Barry, Chester Gould and more! More details...

Where: Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

When: Now until 3 October 2021

Society of Illustraors: Comic Art Exhibition & Sale

Over 180 pieces of original comic book art from EC, Marvel & DC, from 1935 up to the modern era. More details...

Where: Society of Illustrators, New York

When: Now until 23 October, 2021

Marvel Universe of Superheroes

Celebrating Marvel history with more than 300 artefacts - original comic book pages, sculptures, interactive displays and costumes and props from the Marvel blockbuster films. More details...

Where: Museum of Science & Industry, Chicago

When: Now until 24 October 2021

Walt Kelly: Into The Swamp

Celebrating Walt Kelly and his social commentary through the joyous, poignant, and occasionally profound insights and beauty of the alternative universe that is Pogo. More details...

Where: Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, Columbus, Ohio

When: Now until 31 October 2021

The Legend of Wonder Woman

An exhibition celebrating 80 years of DC Comics’ iconic Amazon. More details...

Where: Cartoon Art Museum, San Francisco

When: Now until 31 December 2021

Romanticism To Ruin: Reconstructing the Garrick

Focused on the lost buildings of Louis Sullivan. Co-curated by John Vinci, Tim Samuelson, Chris Ware and Eric Nordstrom. More details...

Where: WrightWood659, Chicago

When: 24 September to 27 November 2021

Marvelocity: The Art of Alex Ross

Featuring original art from his most recent book, Marvelocity, visitors will also learn about how Alex Ross developed into a great illustrator through his childhood drawings, preliminary sketches and paintings. More details...

Where: Canton, Ohio

When: 23 November 2021 to 6 March 2022

COMIC ART MUSEUMS & GALLERIES

UNITED KINGDOM:

British Cartoon Archive

By appointment access to over 200,000 cartoons and comics. More details...

Where: University of Kent, Canterbury

Heath Robinson Museum

A permanent exhibition dedicated to Heath Robinson’s eccentric artistic career. More details...

Where: Pinner, London

Orbital Art Gallery

The gallery space of an awesome comics shop. More details...

Where: Central London

Quentin Blake Center for Illustration

Soon to be home to Quentin Blake's archive of 40,000 works. More details...

Where: Clerkenwell, London

The Cartoon Museum

Celebrating Britain’s cartoon and comic art heritage. More details...

Where: Central London

V&A National Art Library Comic Art Collection

By appointment access to the Krazy Kat Arkive & Rakoff Collection. More details...

Where: South Kensington, London

EUROPE:

Basel Cartoon Museum

Devoted to the art of narrative drawing. More details...

Where: Basel, Switzerland

Belgian Comics Art Museum

Honouring the creators and heroes of the 9th Art for over 30 years. More details...

Where: Brussels

Hergé Museum

Explore the life and work of the creator of Tintin. More details...

Where: Belgium

Le Musee de la Bande Dessinee

A celebration of European comics culture. More details...

Where, Angouleme, France

NORTH AMERICA:

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

The world’s largest collection of materials related to cartoons and comics. More details...

Where: Columbus, Ohio

Cartoon Art Museum

Exploring comic strips, comic books, political cartoons and underground comix. More details...

Where: San Francisco, California

Charles M. Schulz Museum

Dedicated to the life and works of the Peanuts creator. More details...

Where: Santa Rosa, California

Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery

Bookstore and gallery space of the publisher of the world's greatest cartoonists. More details...

Where: Seattle, Washington

Frazetta Art Museum

The largest collection of Frazetta art. More details...

Where: East Stroudburg, PA

Norman Rockwell Museum

Illuminating the power of American illustration art to reflect and shape society. More details...

Where: Stockbridge, MA

Philippe Labaune Gallery

Comic art and illustration by emerging and established artists from around the world. More details...

Where: New York, NY

The Society of Illustrators

Dedicated to the art of illustration in America. More details...

Where: New York, NY

To get your comic art exhibition listed here please send details (ie what, where and when) to:

Read [dot] Yourself [dot] RAW [at] gmail [dot] com

05 August 2021

Los Tejanos by Jack Jackson (No. 95)

Los Tejanos is the story of the Texas-Mexican conflict between 1835 and 1875. Jackson's view of the conflict is seen through the eyes of the tejano (literally Texan of Mexican, as distinct from anglo, heritage) Juan Seguin. It is through Seguin that Jackson humanises and provides scale for this vast and complex story; the history is filtered through his consciousness. Seguin is a pivotal and tragic figure who, due to inexorable political circumstances and innate nationalistic prejudices, was considered suspect to the anglo Texans and, ultimately, a traitor from the Mexican point of view. The equal opportunity hostility directed toward Seguin allows Jackson the luxury of not taking sides (except perhaps Seguin's) that achieves a kind of passionate, hard-won impartiality toward both (or I should say, including the U.S., all three) sides.

There is, to all of Jackson's historical work, an unflinching no-nonsense approach, of which Los Tejanos is characteristic; that no side in this conflict is flattered is a testament to Jackson's own independence as an historian. The lineage of Texas' independence and eventual absorption into the Union is a political snakebite, which Jackson navigates with consummate skill and clarity.

Jackson has managed to compress an intimidating quantity of historical facts and information while never losing sight of the narrative's human dimension by refining the language of comics to serve his unique needs as an historian and comics artist: a heavy reliance on captions combined with an aphoristic visual approach whereby each panel serves as a visual synecdoche, summarising incident or motivation, capturing the essence of an historical moment. Such work could only have been accomplished by an artist who cares deeply about the gravitas of both art and history.

GARY GROTH:

(from Remembering Jack Jackson in The Comics Journal #278, October 2006)

...I'd see Jack every summer at the Dallas-Con. We'd always get together for lunch or dinner or drinks at the end of the night. In person, Jack very much reflected his meat-and-potatoes aesthetic: He had a straight forward, no-nonsense approach to conversation, eschewing bonhomie and bullshit, always focusing in on the salient points, never trying merely to score points, always Socratic and probing by nature. He was never a grandstander and never much concerned with status, either. He busted his ass, was never compensated adequately, and remained stedfast in his creative convictions in the face of indifference, hostility and commercial failure. He knew what he was doing had value. I don't have to point out how rare this kind of commitment is...

Jaxon at Wikipedia

The Jackson Papers

04 August 2021

Feiffer / Sick, Sick, Sick by Jules Feiffer (No. 6)

His quintessential character Bernard Mergendelier, a young urban hippie type destined for a life of mediocrity. He craves power over his own life - his love life, his work, his day-to-day existence - and simultaneously worships and despises anyone who does have that kind of power. Hence his ambiguous relationship with his friend Huey, the Brando-esque jerk to whom all the women flock. Feiffer gives Huey some of his best lines: "Put on your shoes, I'll walk you to the subway' is repeated ironically by R. Crumb's loathsome protagonist in Snoid. The sequence in which Bernard is discussing love and respect while Huey makes eye-contact with a "phoney little magazine chick" is a classic comparison of two types.

It almost seems too much to add that Feiffer is an excellent playwright, screenwriter, and most recently, children's book author. And as a cartoonist, Feiffer's been willing to radically experiment, as best exemplified by the oddly fascinating cartoon novel Tantrum. It is difficult to imagine any other successful strip cartoonist taking such a bold aesthetic risk as Feiffer did with Tantrum.

But his weekly strip remains his most influential work. In the world of daily strips, it is impossible to conceive of Doonesbury without Feiffer. And perhaps more important, he showed cartoonists that it was possible to have relatively uncensored, adult-oriented weekly comic strips. As underground newspapers evolved into alternative newsweeklies all over America, Feiffer's descendants proliferated. Without Feiffer, there may have been no weekly strips be Matt Groening, Lynda Barry, Ben Katchor, Kazans, Carol Lay, Tony Millionaire, Tom Tomorrow and many other. But few of these younger cartoonists have yet matched the brilliance of the first 10 years of Sick, Sick, Sick.

TCJ: A Conversation with Jules Feiffer (2014)

TCJ: The Jules Feiffer Interview (1988)

The Great Comic Book Heroes by Jules Feiffer (1965)

03 August 2021

The EC War Comics by Harvey Kurtzman & Others (No. 12)

It was this crusade that inspired Kurtzman's legendary passion for research. Only the truth can eradicate a lie, and to tell the truth, one needed to study history and news reports in order to unearth fact and to be able to portray facts accurately. Kurtzman had been impressed with Charles Biro's storytelling in the Lev Gleason crime comic books. "He offered stories based on fact, presented in a hard-edged documentary style, a highly original approach to comics back then," Kurtzman said. He recalled the excitement he felt reading those stories, "the shock" of being brought "nose-to-nose with reality." He set out to do the same thing with his war stories. The realities of the battlefield would destroy the phony, glamorous vision of war.

But Kurtzman's war stories were not anti-war: in deglamourising warfare, he did not oppose the effort in Korea. His stories acknowledged the necessity of the fight - not only in Korea but in wars generally. Against that necessity, Kurtzman balanced recognition of the over-all futility of warfare. His unique achievement was to strike the balance. But in those days - in the wake of the superpatriotism of World War II just concluded, during another war in which veterans of the previous conflict were also fighting and dying - to publish such a balanced view was extraordinarily unprecedented. While Kurtzman's stories recognised the causes of wars and the necessity of fighting them, he dramatised the loss, the profligate waste of human life that characterised war everywhere in every time.

To show these consequences, Kurtzman's stories often focused on the fate of a single individual. One story chronicled in elaborate detail the steps a Korean farmer took in building his house - picking a site, laying the foundations, erecting a framework, making bricks, putting it all together. Then on the day he finishes his work, a bomb falls on the house and in a second destroys the painstaking labour of months. In another story, a dying soldier wonders about the arbitrariness of timing: if he hadn't stopped for a moment to tie his shoe, he would have been 20 feet further down the road and when the bomb hit - he would have been far enough away to survive.

In telling the stories, Kurtzman paced his narrative more dramatically than others did at the time. To focus on a key sequence, for instance, he sometimes deployed a series of almost static visuals, the progression of the panels building to a conclusion with "voice-over" captions while the camera tracked in for a final close-up, giving the last moment of the sequence emotional intensity. This restrained kind of manoeuvre gave his stories the even-handed patina of a documentary, enhancing their realistic aura. A stickler for execution, Kurtzman painstakingly laid out every page of his stories, penciling in the action and the verbiage; and he demanded that the illustrators follow his layouts exactly.

02 August 2021

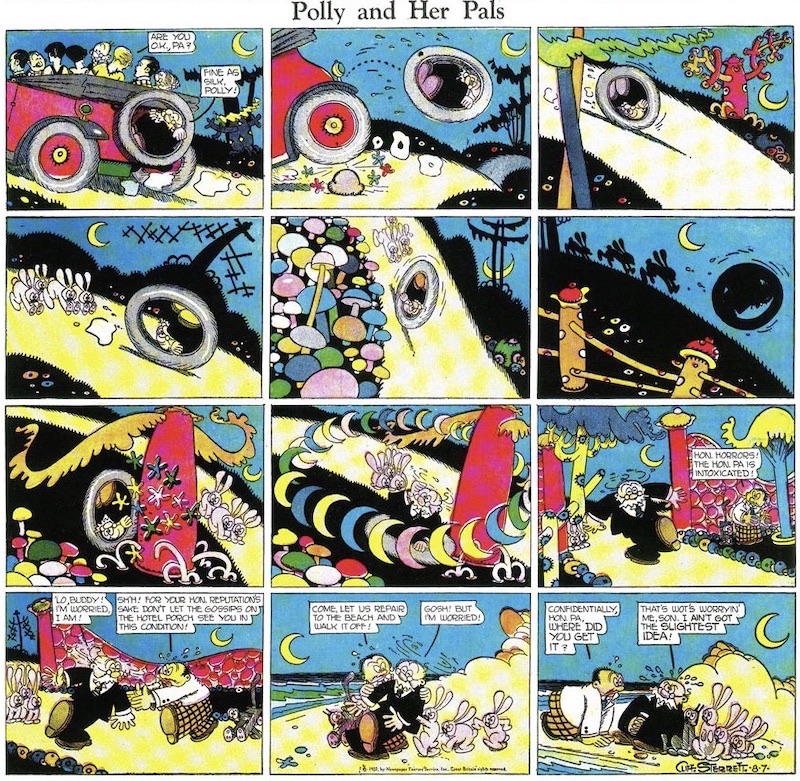

Polly & Her Pals by Cliff Sterrett (No. 18)

Although Sterrett (1883-1964) changed the strip's title to indicate its broadening focus, even Polly & Her Pals does not reflect the true basis of the comedy - the clash of mores between generations. Paw's exasperated outrage inspired most of the laughter, and he was soon the star of the strip. To wring everything he could from the situation, Sterrett surrounded the old man with a cast of idiosyncratic secondary characters whose assorted eccentricities were designed expressly to assail Paw with modernity in all its variations and varieties. Polly eventually faded into the background, but in the early days of the strip, she attracted considerable attention for daring to display her long legs. And in her facial profile - bulging brow, tiny nose, pouting mouth - Sterrett established a convention for depicting a pretty girl's face that was widely adopted by other cartoonists. But little else about Sterrett's way of drawing could be readily imitated.

As his style matured in the mid-twenties, Polly became a spectacular symphony of line design in black and white in daily strips and a riot of primary colours on Sundays - rampant reds, succulent yellows, pristine blues. The stylistic earmark was the interplay of patterned line and geometric shape. Checks, strips, black solids, quilt-like patchworks, and surrealistic backgrounds were juxtaposed in panels populated by creatures whose anatomy was wholly abstract, completely geometric in cubism's Futuristic manner: heads were simple spheres; bodies and limbs, cylindrical tubes. This abstraction of the human form permitted widely unrealistic but supremely comic expressiveness in both face and feature, and Sterrett exploited the possibilities with playful exuberance.

Kitty, the family pet, for instance, became a completely geometric cat, assuming a larger significance in the strip's motif: her geometry made her as anthropomorphic as her owner, and she emerged as a Greek chorus, commenting on Paw's predicaments by outright imitation of his actions or in her exaggerated reaction to his moods.

Inspired by the surrealistic impulses of modern art as well as Futurism, Sterrett's Sunday pages in the late twenties in particular were unparalleled in their comic distortions of reality, in their subordination to abstract design of the representational mission of the drawings. The pages were agog in exotic potted plants, fanciful embroidered pillows, abstracted cityscapes, outlandish tubular trees with electric foliage zig-zagging across the sky. Any many of the gags seemed dictated by Sterrett's desire to draw certain subjects in certain ways, often experimental. It's midnight on one Sunday and the panels are mostly black, the action revealed solely in patches of light; on a Sunday at the beach, all the action id depicted under water, and we see only the distorted bottom portions of the characters wading.

By the 1930s, Sterrett's drawings were less inventive: the surrealistic elements disappeared, leaving just the geometric forms of Futurism, and these had become mere conventions. Suffering from arthritis, Street surrendered the art chores on the dailies to an assistant; the last Sunday Polly was published June 15, 1958.

01 August 2021

Covering The New Yorker: Adrian Tomine

Between the ages of 17 and 20, Adrian Tomine self-published 7 issues of his mini-comic Optic Nerve, which comprised of short stories displaying the first hints of the distinctive, realist style that he would go on to perfect. In 1994 Optic Nerve was subsequently published for 14 issues by Drawn & Quarterly and would be where his acclaimed graphic novels (Sleepwalk & Other Stories, Summer Blonde, Shortcomings and Killing & Dying) would be first serialised.

His Eisner Award winning book, The Loneliness of a Long-Distance Cartoonist, was published in 2020, which Alan Moore described as:

"In this heartfelt and beautifully crafted work, Adrian Tomine presents the most honest and insightful portrait you will ever see of an industry that I can no longer bear to be associated with."

You have a distinctive palette of muted, neutral tones, yet you’ve still managed to highlight your subject against the background. How important is light in your compositions?

I’ve wasted an insane amount of time thinking about lighting in Zoom meetings, so it seemed fitting that it would be central to this image. I’d love to be one of those effortlessly beautiful people who can just open their laptop in a dark room and look terrific, but, instead, I’m often rearranging entire rooms, running extension cords to various lighting sources, and scheduling meetings based on when I can get natural window light. Also, I was looking at Edward Hopper as I was working on this, and light was probably the most consistent thread that ran through his work.

You recently published a book, “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist,” which makes a cameo on this cover. The book was very well received. Did the praise help you with the next project, or paralyze you?

Everything paralyzes me, whether it’s praise or criticism. Somehow I always find a way to carry on and to keep making things, but there’s literally no reaction to my work that I can’t twist into something to obsess over.

In your book, and in your New Yorker covers, you seem to home in on painful moments to find the humor in them. Do you experience a eureka moment when you locate that contradiction?

I think that’s a good way of putting it. To be honest, I don’t know how someone could get through life without being able to bask in that contradiction. In my personal life, I’ve often felt very moved by that act of finding humor in pain. If someone can authentically pull that off and be really funny, that’s worth more than a hundred words of earnest consolation to me.

I know you and your wife have been confined at home with two young children—but what’s with the cat? Is that from life or from your imagination?

That’s my tribute to our cats, Dolly and Pepper. Dolly passed away, unfortunately, but it felt nice to immortalize her in this way. I’ve drawn every other member of our household on the cover at some point, so it seemed only fair. (For the record, we keep the litter box in a much more socially distanced location.)

Sometimes a cover image will just appear in my mind, fully formed. In other cases, I’ll have the vaguest semblance of an idea but no sense of how to turn it into a cover. Those movie-set trailers are a good example of this. I’d drawn them in my sketchbook a long time ago, and I knew they were an ubiquitous, specific part of New York life, but I didn't have a story beyond that. Then, a few years ago, I decided to try my hand at screenwriting, and in a particular moment of frustration and despair this image popped into my mind. The apron on the back of the chair was a spur-of-the-moment addition while I was sketching, and I think that was the last piece I was looking for.

I think New York is one of those cities where, whatever your ambition is, you can look around and instantly see someone achieving that dream, often at a level that you never even knew was possible. That experience can be dispiriting, but also extremely inspiring, and that’s part of what I was trying to capture.

Spending time in nature is something I do solely for the happiness of my children, like going to puppet shows or listening to Katy Perry. I can wander around the city with my kids, potentially surrounded by psychopaths, and I’m completely at ease. But put us in some tall grass, and all my neurotic, protective instincts come out.

Where I live in Brooklyn, there’re always a lot of books being set out on the sidewalk, and there’re also a lot of authors walking around the neighborhood. Lifelong New Yorkers may take for granted the sight of people setting stuff on their steps to give away, but I still notice it. I’ve had the experience of seeing stacks of New Yorkers with my cover out on the street, though I haven’t seen my books put out - but then, I also don’t have a giant photo of myself on the back cover.

I think it's kind of beautiful and hilarious to see people eating their organic kale and quinoa salads while gazing across the opaque, fetid water. It’s strange to see the recent proliferation of health-conscious and environmentally conscious restaurants and grocery stores, right next to the piles of scrap and rubble. I guess it proves that there's no part of the city that can't be revitalized, recontextualized, or ruined - depending on your point of view.

When I heard that the 9/11 memorial and museum were going to be the top tourist attractions in New York this summer, I first sketched only tourists going about their usual happy activities, with the memorial in the background. But when I got to the site, I instantly realized that there was a lot more to be captured - specifically, a much, much wider range of emotions and reactions, all unfolding in shockingly close proximity. I guess that’s the nature of any public space, but when you add in an element of such extreme grief and horror, the parameters shift.